During the fourth hottest June on record in Tucson, researchers surveyed the city in mobile observatories to assess neighborhood level climate and heat impacts.

The high-tech, weather-chasing trucks belong to Brookhaven National Laboratory, who is partnering with researchers at the University of Arizona to study extreme heat in the Southwest. Researchers said the mobile labs are the only two of their kind in the world, and are uniquely outfitted to monitor localized climate data.

The mobile data collection effort is part of the Department of Energy funded Southwest Urban Corridor Integrated Field Laboratory, a partnership between the state’s three universities, and Brookhaven National Laboratory as well as others.

“The big picture for the Southwest IFL is that we’re looking at climate change across the Arizona urban corridor, modeling observations, and translating all of that into resilient solutions for community partners,” said Ladd Keith, an associate professor of urban planning at UA and the union institutional lead for the Southwest ISL.

This summer is an intensive observation period for the team. Katia Lamer, director of the center for multiscale applied sensing at Brookhaven National Laboratory, along with Edwin Davis and Parag Joshi, have spent the last few weeks traveling predetermined routes around Phoenix and Tucson, to gather accurate readings around the cities, and analyze heat and air quality differences across the metropolitan areas.

“There’s a real need to better understand extreme heat and related hazards,” Lamer said. “So we’re measuring how this extreme heat varies from community to community.”

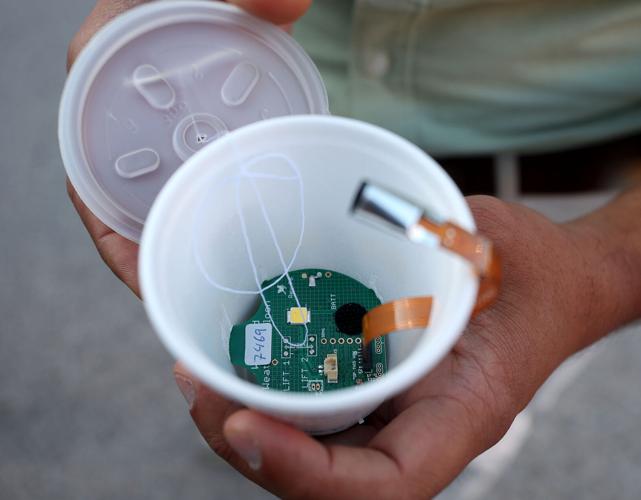

Both state of the art rigs are equipped with an array of different instruments that collect temperature readings, air quality measurements, and monitor air pollution levels. Radar scanners on board allow the team to see where rain is in the sky and measure cloud cover. It’s almost like something out of a sci-fi movie.

They also utilize two different kinds of weather balloons to take atmospheric readings, the lowest maxing out at about nine kilometers while the larger balloons can reach up to 26 kilometers, about 16 miles.

“Each instrument basically tells us a different piece of the climate system,” Lamer said. “We have our lasers that shoot invisible light to the sky and are able to detect aerosol or air pollution particles. They’re able to tell us information about the concentration, so where the pollution tends to accumulate in the sky.”

The readings can also help Lamer’s team understand how that pollution affects urban heating,

The trucks are fully off the grid and self-sustaining with their own power generator, and data storage and computers on board, and the instruments are designed to be easily transferred to other modes of transport, or shipped.

As the mobile observatories drive through the city, they take readings and collect climate, heat and air quality data at a neighborhood scale, something that is not possible with stationary weather monitoring systems.

“We’re able to track air quality at the street level where people live. So we use a combination of street level measurement and upper atmosphere measurements to get the full picture of the climate system,” Lamer said.

That includes mapping the heat dome around cities, and measuring the impact of large green spaces and different types of building structures on air quality and temperature.

While the results of the study are still preliminary, Lamer said that there are already noticeable discrepancies in readings throughout the city.

“The data is telling us that there is some variability in the different neighborhoods of Tucson,” she said.

“We’re really interested to see the improvements that the city of Tucson is putting into place along the Oracle Road neighborhoods, and things like improved bus stops, new storm water infrastructure, and urban forestry,” Keith said. “We hope to come back and measure those improvements in the future and have more information about how much they reduce heat or reduce air pollution.”

The data gathered by the mobile laboratories will help inform future research on climate effects on cities in the south west, and hopefully inform local climate policy.

“This is really our pilot opportunity to see what kind of data we can collect, and what can we learn about our urban areas in Arizona, how the heat island is formed, which areas may be hotter than other areas, which areas have higher air pollution, and give that back to our city decision makers,” he said.

The data gathered could be made available for the public as early as December, Lamer said.