In what would be an unprecedented move, the U.S. Interior Department is considering an action that would create a possible, immediate cutback in Colorado River water supplies to Arizona, California and Nevada: holding back nearly a half million acre-feet of water it had planned to release this year from Lake Powell to Lake Mead.

In a letter Friday to all seven Colorado River Basin states' top water officials, Assistant Interior Secretary Tanya Trujillo wrote that such a possible cutback would be aimed at keeping Powell from falling below the elevation at which electricity couldn’t be generated at Glen Canyon Dam.

Trujillo warned of possible major risks to the dam’s operations and infrastructure if Powell falls below the “minimum power pool” level of 3,490 feet.

If that happened, it would raise concerns about the dam’s ability to deliver water to the Lower Basin states of Arizona, California and Nevada, wrote Trujillo, Interior’s assistant secretary of water and science.

“In such circumstances, Glen Canyon Dam facilities face unprecedented reliability challenges, water users in the basin face increased uncertainty, downstream resources could be impacted, the Western electrical grid would experience uncertain risk and instability and water supplies to the West and Southwestern United States would be subject to increased operational uncertainty,” Trujillo wrote.

Her letter asked water officials in the seven states to comment on a “potential” 480,000-acre-foot cut by April 22. The cut would be effective in “water year” 2022, which runs from October 2021 through September 2022.

Trujillo also warned that without a change in river flows, which would require a break in the recent arid conditions, it may not be possible to avoid operating Lake Powell below 3,490 feet.

“This reality reinforces the need for the basin states, and all entities in the basin, to prioritize work to further conserve and reduce use of Colorado River water to stabilize the system’s reservoirs,” she wrote.

A midyear delivery cut of this scale would remove about 6.5% of the 7.48 million acre feet the lower basin was to receive this year from Powell.

But that cut would still further slash elevations at already depleted Lake Mead, triggering major concerns among water users about the certainty and reliability of future deliveries, said Kathryn Sorensen, a research fellow at Arizona State University’s Kyl Center for Water Policy.

“The letter points to how dire conditions are on the Colorado River and, I think, the big picture is that communities have a responsibility to make sure there is water at the tap. If they haven’t already put contingencies in place to be able to deliver alternative water supplies, we need to do it now,” Sorenson said.

“Certainty is really important to water planners, but in an increasingly volatile system that certainty is going to be hard to come by,” she said.

Today, the river basin faces the 22nd year of what some scientists call this region’s worst drought in 1,200 years.

The Lower Basin states, including Arizona, had already cut back more than 500,000 acre feet in deliveries this year, following a 2019 drought contingency plan. That’s the equivalent of enough water to serve 2 million households if they consume water at Tucson’s rates.

Hardest hit was the Central Arizona Project, a 336-mile canal stretching from the river to Tucson, with cuts particularly smacking farmers in Pinal County northwest of Tucson.

But as reservoirs keep falling due to drought and climate change, Interior’s Bureau of Reclamation was already considering releasing more water from upstream reservoirs in the Upper Basin states of Utah, Colorado and New Mexico, to prop up Powell. A plan for such releases is to be finished this spring.

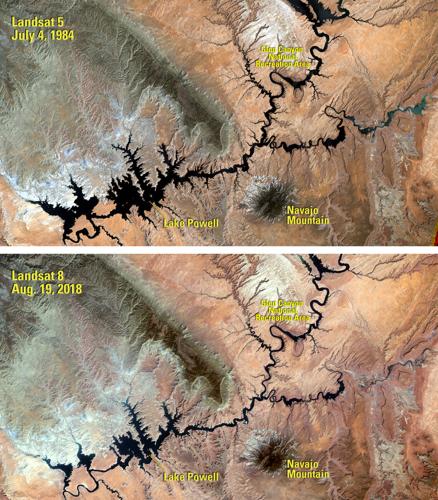

Top: Landsat image of Lake Powell at its peak water level in 1984. Bottom: Landsat image of Lake Powell in 2018.

But in March, Lake Powell for the first time dropped below 3,525 feet, the level acting as a buffer against the possibility of it falling to 3,490 feet at which the dam’s turbines could no longer operate. On Sunday, Powell stood at 3,522.9 feet, nearly 40 feet below its April 2021 elevation and more than 75 feet below that of two years ago.

The bureau has forecast a nearly 1 in 4 chance of Powell falling below 3,490 from 2023 through 2026.

Now, Interior officials are concerned that more actions are needed to reduce the risk of power generation being curtailed, Trujillo wrote. Below the 3,490 feet elevation, water releases to the Lower Basin would have to be delivered through “outlet tubes,” massive steel structures lying at the foot of the dam.

“Glen Canyon Dam was not envisioned to operate solely through the outlet works for an extended period of time, and operating at this low lake level increases risks to water delivery and potential impacts to downstream resources and infrastructure,” Trujillo wrote.

“In addition, should Lake Powell decline further below 3,490 feet, we have confirmed that essential drinking water infrastructure supplying the City of Page, Arizona and the LeChee Chapter of the Navajo Nation could not function,” Trujillo said. Page, population about 7,530, adjoins Lake Powell.

“Given our lack of actual operating experience in such circumstances, these issues raise profound concerns regarding prudent dam operations, facility reliability, public health and safety and the ability to conduct emergency operations,” Trujillo wrote.

The bureau is committed to safely operating the dam and maintaining reliable reservoir releases, she said. But in today’s low runoff conditions, “we are approaching operating conditions for which we have only very limited actual operating experience — and which occurred nearly 60 years ago,” Trujillo said.

in a statement, the Arizona Department of Water Resources said that ADWR Director Tom Buschatzke "is evaluating the actions contained in the letter. He recognizes that the increased operational uncertainties present serious risks with substantial potential impacts to the resources and stakeholders reliant upon the river and the infrastructure on the river."

The Southern Nevada Water Authority said in a statement that, "Conditions on the Colorado River are serious, and we are committed to working with the Bureau of Reclamation and our partners on the river in accordance with the operating guidelines to identify and develop responsive strategies as requested by April 22.”

The statement referred to guidelines for operating the river's reservoirs, including Powell and Mead, that the seven states and the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation approved back in 2007.

But if the region’s arid conditions persist beyond this year, “I think there will be immense pressure to find another solution” beyond the cuts currently proposed, said Sarah Porter, the Kyl Center’s director.

“No one has adequately studied what happens if Glen Canyon Dam isn’t producing power. I don’t think we’ve adequately looked into the capacity of the grid to provide redundant power supply,” Porter said.

As for Lake Mead, Porter noted that it’s important to realize that as the lake falls, its rate of decline accelerates “due to the lake’s inverse pyramid shape.”

Photos: Glen Canyon Dam dedicated in 1966 after years of construction

Glen Canyon Dam

Updated

Glen Canyon Bridge and Glen Canyon Dam during the official dedication of Glen Canyon Dam near Page, Ariz. on Sept. 22, 1966.

Glen Canyon Dam

Updated

Interior Secretary Stewart Udall, right, with Ladybird Johnson during the official dedication of Glen Canyon Dam near Page, Ariz. on Sept. 22, 1966. The Glen Canyon Bridge is in the background.

Glen Canyon Dam

Updated

First Lady Ladybird Johnson with Arizona Gov. Sam Goddard during the official dedication of Glen Canyon Dam near Page, Ariz. on Sept. 22, 1966.

Glen Canyon Dam

Updated

The transformer complex during the official dedication of Glen Canyon Dam near Page, Ariz. on Sept. 22, 1966.

Glen Canyon Dam

Updated

The control room during the official dedication of Glen Canyon Dam near Page, Ariz. on Sept. 22, 1966.

Glen Canyon Dam

Updated

Deep underneath Glen Canyon Dam during the official dedication of Glen Canyon Dam near Page, Ariz. on Sept. 22, 1966.

Glen Canyon Dam

Updated

A giant steel turbine shaft spinning during the official dedication of Glen Canyon Dam near Page, Ariz. on Sept. 22, 1966.

Glen Canyon Dam

Updated

First Lady Ladybird Johnson, center, during the official dedication of Glen Canyon Dam near Page, Ariz. on Sept. 22, 1966.

Glen Canyon Dam

Updated

First Lady Ladybird Johnson during the official dedication of Glen Canyon Dam near Page, Ariz. on Sept. 22, 1966.

Glen Canyon Dam

Updated

Wahweap Marina on Lake Powell during the official dedication of Glen Canyon Dam near Page, Ariz. on Sept. 22, 1966.

Glen Canyon Dam

Updated

Boaters on the new Lake Powell during the official dedication of Glen Canyon Dam near Page, Ariz. on Sept. 22, 1966.

Glen Canyon Dam

Updated

The turbine hall during the official dedication of Glen Canyon Dam near Page, Ariz. on Sept. 22, 1966. The first electricity was generated on September 4, 1964, with the power sent into the regional electric grid through a pair of long-distance transmission lines as far as Phoenix, Arizona and Farmington, New Mexico.[

Glen Canyon Dam

Updated

The eight penstocks that provide water for generation of electricity are revealed on the back of Glen Canyon Dam during the official dedication of Glen Canyon Dam near Page, Ariz. on Sept. 22, 1966.

Glen Canyon Dam

Updated

A man catches some sun during the official dedication of Glen Canyon Dam near Page, Ariz. on Sept. 22, 1966.

Glen Canyon Dam

Updated

Boaters on Lake Powell during the official dedication of Glen Canyon Dam near Page, Ariz. on Sept. 22, 1966.

Glen Canyon Dam

Updated

Boaters on Lake Powell during the official dedication of Glen Canyon Dam near Page, Ariz. on Sept. 22, 1966.

Glen Canyon Dam

Updated

A guest photographs Arizona's newest lake during the official dedication of Glen Canyon Dam near Page, Ariz. on Sept. 22, 1966.

Glen Canyon Dam

Updated

Spectators watch the dignitaries from a distance during the official dedication of Glen Canyon Dam near Page, Ariz. on Sept. 22, 1966.

Glen Canyon Dam

Updated

A boat ride on Lake Powell during the official dedication of Glen Canyon Dam near Page, Ariz. on Sept. 22, 1966.

Glen Canyon Dam

Updated

Wahweap Marina on Lake Powell during the official dedication of Glen Canyon Dam near Page, Ariz. on Sept. 22, 1966.

Glen Canyon Dam

Updated

Photograph of a bend in Glen Canyon of the Colorado River, Grand Canyon, ca.1898. The towering nearly-vertical rocky canyon walls loom over the placid river. The canyon rim is visible in the distance. A rocky embankment forms the shore on one side of the river. Two men row small boats on the river.

Glen Canyon Dam

Updated

Glen Canyon damsite from the air in November 1957, prior to construction of the Glen Canyon Bridge

Glen Canyon Dam

Updated

Aerial view of Glen Canyon Dam during construction - 1962

Glen Canyon Dam

Updated

Construction of Glen Canyon Dam in 1963.

Glen Canyon Dam

Updated

Lake Powell filling underway, 1965

Glen Canyon Dam, bridge, construction

Updated

Steelworkers sit on the steel span for Glen Canyon bridge under construction high above the Colorado River in the late 1950s.

Glen Canyon Dam, bridge, construction

Updated

The bridge span emerges from the anchorage in the wall of Glen Canyon just west of the dam site under construction, late 1950s.

Glen Canyon Dam, bridge, construction

Updated

Heavy equipment moving rock at Glen Canyon Dam site, late 1950s.

Glen Canyon Dam, bridge, construction

Updated

Dozens of survey marks dot the wall of Glen Canyon at the site of the dam in the late 1950s.

Glen Canyon

Updated

Bend in Glen Canyon of the Colorado River, Grand Canyon, ca.1898. Photographer: George Wharton James