Could stopping the progression of a horrible disease be possible by studying something as insignificant seeming as a fruit fly?

A pair of University of Arizona scientists hope so after the tiny bugs recently helped them understand something complex about Lou Gehrig’s disease.

First, here’s why they study the flies: The insects’ neurological systems are a surprisingly accurate representation of human systems. In fact, approximately 75% of genes linked to human diseases have a closely related gene in the fruit fly.

“We have very similar organs although the fruit fly brain is obviously significantly smaller,” said Daniela Zarnescu, a UA molecular and cellular biology professor. The nervous system? The exact same pieces.

Also called amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS, Lou Gehrig’s disease involves the deterioration and death of nerve cells that help with voluntary movements such as breathing, walking, talking and eating.

It’s named after the New York Yankees baseball player who developed the disease in 1939 and died in 1941.

Most patients die within two to five years of being diagnosed due to respiratory failure.

Zarnescu began this research in 2008 with $25,000 from a foundation started by the family of Jim Himelic, a Pima County Juvenile Court judge who died of ALS in 2000.

Zarnescu and Erik Lehmkuhl, a molecular and cellular biology graduate student, have been studying a protein called TDP-43 that’s often found forming clumps within the cells of people with ALS, thereby disrupting the creation of healthy protein and causing cells to die.

They weren’t sure how this contributed to ALS until they realized an important victim of TDP-43 in the flies called Dlp, which is short for Dally-like protein. In people, its equivalent is called GPC6. By studying how TDP-43 protein was stopping the production of healthy Dlp cells in fruit flies, they have been able to see how it might be happening the same way in people with ALS.

Additionally, Zarnescu said, they discovered TDP-43 protein is not only clumping itself in the flies, but it’s also causing Dlp to clump, and that also could lead to a greater understanding about what’s happening in people with ALS.

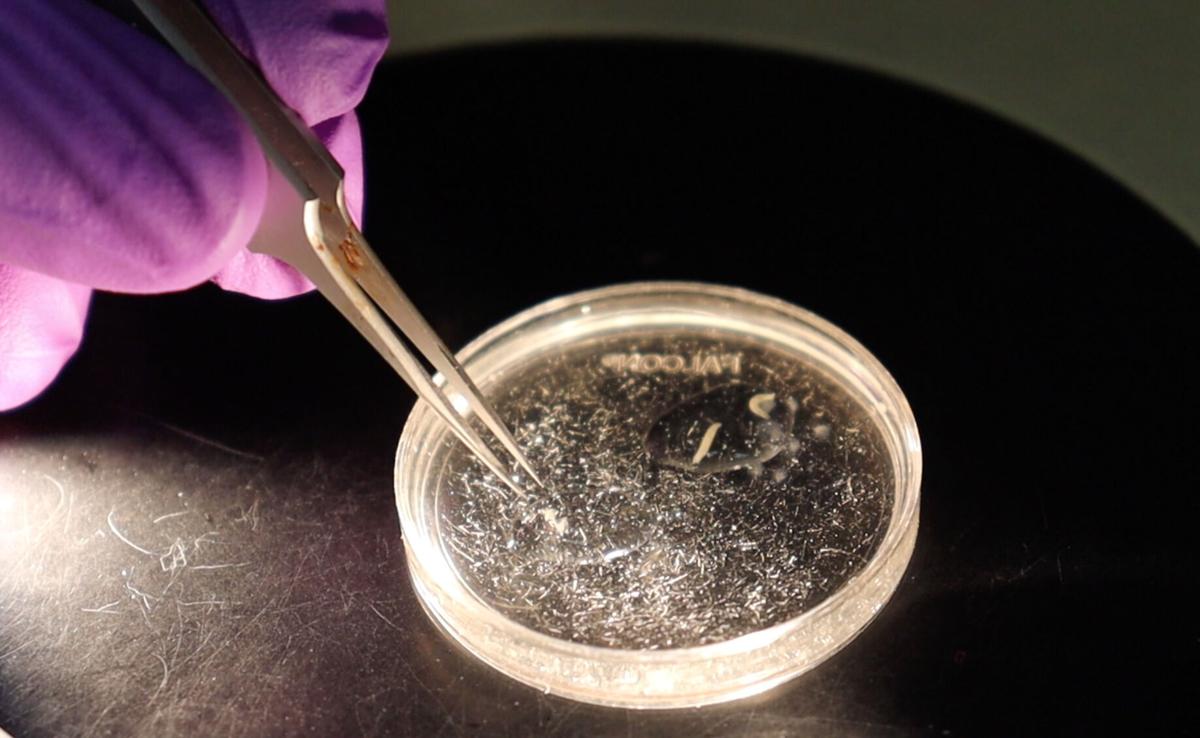

University of Arizona molecular and cellular biology graduate student Erik Lehmkuhl explains why fruit flies can help scientists learn more about Lou Gehrig's Disease. Courtesy of MIchele Vaughan / University of Arizona 2021

“The clumps were unexpected but they are also present in (ALS) patients so I expect they will tell us something important about the disease and how to treat it,” she said.

The findings, published recently in Acta Neuropathologica Communications, shows that when TDP-43 reduces Dlp in the fly, locomotor problems happen in the same way as they do with ALS patients. And when researchers restore the Dlp protein in the fruit flies, the insects’ ability to move returns.

The next step in this research is seeing if the same thing can happen in people with ALS.

“Although extensive work still needs to be done to understand how Dlp/GPC6 dysregulation affects neuron health and how to take advantage of these discoveries medicinally, we’ve discovered an important piece of the puzzle regarding how ALS progresses,” Lehmkuhl said.

Understanding this could also help researchers eventually understand other neurodegenerative diseases as well, he said. These include frontotemporal dementia, Alzheimer’s disease and chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE, which is brain degeneration likely caused by repeated head traumas.