The border near Tucson doesn't fit the mold of the crisis playing out in the Rio Grande Valley in Texas, according to federal data and local Border Patrol officials.

Broadly put, most of the recent migration in the Border Patrol's Tucson Sector involves adults from Mexico and Guatemala who are quickly expelled to Mexico. The Rio Grande Valley Sector, on the other hand, is seeing tens of thousands of families and children from Honduras, which prompted the Biden administration to rush to find temporary housing for them.

As policymakers issue statements and call for more action from the Biden administration, either to provide more support to migrant families and children or to resume strict policies from the Trump administration, they risk crafting policies that gloss over important differences in how the recent rise in border encounters is playing out in each area of the border.

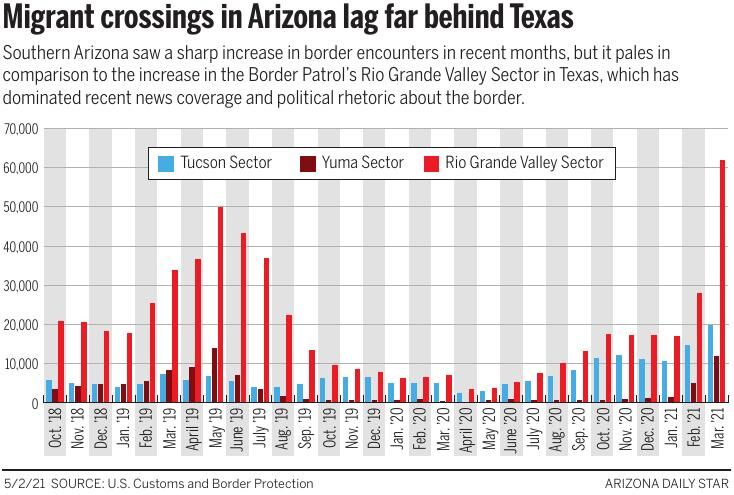

Rather than deal with the details, the national political conversation focused on the 172,000 border encounters reported by Customs and Border Protection officials for March, which surpassed the peak of a similar increase two years ago. That number appeared repeatedly in headlines, cable news shows, and political debates as a shorthand for "Biden's border crisis."

When Gov. Doug Ducey declared an emergency in Arizona's border counties, he cited "more than 170,000 apprehensions at the Southwest border," rather than numbers for the Arizona border.

But the number of migrants encountered, how they travel, where they come from, and how federal officials deal with them vary among Border Patrol sectors.

Even within Arizona, the differences are stark between the border near Tucson and the border near Yuma, where thousands of adult migrants and families are coming from countries like Cuba, Venezuela and Brazil, according to Customs and Border Protection data.

"Not the same border"

To clarify the situation, Interim Tucson Sector Chief Patrol Agent John Modlin answered reporters' questions in mid-April and the Arizona Daily Star analyzed CBP data, with a focus on the Tucson, Yuma and Rio Grande Valley sectors.

"This is not the same border as what you're seeing on the national news in the Rio Grande Valley," Modlin said. “Very different what’s going on over there and what’s going on here."

The clearest difference among the sectors is the total number of encounters. In March, the Rio Grande Valley Sector saw about 62,000 border encounters, compared with about 19,800 in the Tucson Sector and 11,800 in the Yuma Sector.

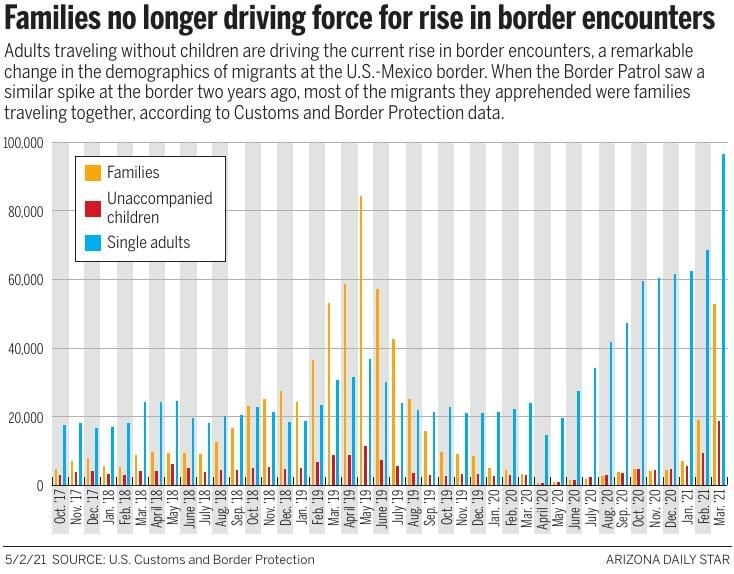

The sectors also differ in whether migrants travel in large groups, as adults without children, as families or as children without their parents.

In the Rio Grande Valley, agents often see large "give-up groups" that include 100 or more migrants flagging down Border Patrol agents, but that is much less common in the Tucson Sector, said Modlin. Instead, most migrants in the Tucson Sector are "actively trying to evade detection."

Large groups are the "new normal" in the Rio Grande Valley Sector, according to social media posts by Chief Patrol Agent Brian Hastings. Agents in the Yuma Sector encounter large groups on a "regular basis," according to Chief Patrol Agent Chris Clem. The posts from the Tucson Sector show only a handful of large groups encountered in recent months.

This is a sharp contrast not only among sectors, but also to the spike in asylum-seeking families in late 2018 and early 2019. During that time, the Tucson Sector chief's posts showed numerous large groups crossing the border southwest of Tucson, where they flagged down agents. Many of those groups were made up of families from Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador.

Now, adults traveling without children account for most of the migrants encountered in the Tucson Sector, as well as in every Border Patrol sector except the Rio Grande Valley and Yuma, according to CBP data.

In March, single adults accounted for 78% of all encounters in the Tucson Sector, a much higher rate than the 27% in the Rio Grande Valley Sector and the 49% in the Yuma Sector.

Families and children

In terms of migrants traveling as families, "our numbers are quite small versus" the Rio Grande Valley Sector, Modlin said. "They are slightly going up, but we're nowhere near where we were."

Families accounted for 10% of all encounters in the Tucson Sector in March, well below the 57% in the Rio Grande Valley Sector and the 44% in the Yuma Sector.

Much of the attention paid to the border in recent months focused on children traveling without their parents, categorized by CBP as unaccompanied children. The Biden administration is scrambling to move those children from CBP custody to the Office of Refugee Resettlement, which places them with family or sponsors in the United States.

The Tucson Sector saw the number of unaccompanied children nearly triple from 865 in January to about 2,300 in March, which prompted CBP officials to award a contract worth up to $105 million to build and run a 80,000-square-foot facility to house them temporarily in Tucson.

Still, unaccompanied children accounted for just 12% of encounters in the Tucson Sector in March, compared with 16% in the Rio Grande Valley Sector and 6% in the Yuma Sector, where CBP built a facility similar to the one in Tucson.

The percentages among the three sectors are not too far apart, but the actual number of unaccompanied children encountered in each sector differs dramatically. In March, the Yuma Sector saw about 800, compared to about 9,700 in the Rio Grande Valley Sector.

Nationality differs

The three sectors also differ dramatically in the nationalities of migrants.

With the statistics released this month, CBP started providing ongoing data about nationality for each sector, instead of the border as a whole. CBP grouped the data in a period covering Oct. 1 to the end of March, rather than monthly totals.

In the Tucson Sector, the most common nationality was Mexico, which accounted for 61% of all border encounters, followed by 30% from Guatemala, 4% from countries labeled as "other," 4% from Honduras and 1% from El Salvador.

The most common nationality in the Rio Grande Valley Sector was Honduras, which accounted for 38% of all border encounters, followed by 24% from Mexico, 22% from Guatemala, 12% from El Salvador and 4% from countries labeled as "other."

In the Yuma Sector, about 58% of border encounters involved migrants from countries labeled as "other," followed by 21% from Mexico, 10% from Guatemala, 8% from Honduras and 2% from El Salvador. The "other" category in Yuma is made up mainly of migrants from Cuba, Venezuela and Brazil.

Young unaccompanied migrants wait for their turn at a processing station inside a U.S. Customs and Border Protection facility in the Rio Grande Valley, in Donna, Texas. The Border Patrol's Rio Grande Valley Sector is seeing tens of thousands of families and unaccompanied children.

Quick expulsions common

Federal officials deal with migrants differently in each sector, particularly with regard to a pandemic public-health order known as Title 42. Under that order, which the Trump administration put in place in March 2020 and the Biden administration has maintained, officials can quickly expel migrants to Mexico.

In the Tucson Sector, officials expelled about 86% of the migrants they encountered from Oct. 1 to the end of March. The vast majority were single adults from Mexico and Guatemala, but more than 4,000 family members and unaccompanied minors, mostly from Mexico and Guatemala, also were expelled.

The Mexican government generally accepts migrants from Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador, but not from many other countries, Modlin said, which “absolutely” explains why most of the families the Border Patrol released to local shelters were from Cuba, Venezuela and Brazil.

In the Rio Grande Valley Sector, officials expelled about 61% of the migrants they encountered, mostly single adults from Mexico, Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador. Officials also expelled about 17,000 family members and unaccompanied minors, mostly from Honduras and Guatemala.

In the Yuma Sector, officials expelled about 36% of the migrants they encountered. Single adults from Mexico accounted for nearly half of those expulsions. Nearly 2,300 family members from various countries also were expelled.

The next round of CBP statistics, which will cover border encounters in April, likely will be released in the first or second week of May.