Nicholas Sofka’s backyard is unlike most. First, there’s the sandbox, filled with over 30 tons of sand. Just a few feet away towers a silver slide and several handmade jungle gyms — one named the lifeboat, welded into the shape of a ship, and another made from an industrial-sized spool.

Then there are the chickens, roosters, ducks, a yellow Labrador and, of course, the three classrooms. Sofka lives above Highland Free School, a charter school he opened in 1970 that’s celebrating its 50th anniversary.

The K-6 school’s alternative education revolves around a small teacher-to-student ratio. With an average of 60 students annually enrolled, three teachers, two aides, and Sofka himself, Highland has been able to maintain around a 1:10 teacher-student ratio for decades.

The balance allows teachers to provide personal attention and tailor lessons to every child’s pace.

“I can actually do my job as a teacher here, I can actually teach,” said Kelly Murphy, who has worked at Highland Free School for 19 years.

But the low ratios come at a price. As charter schools don’t receive funding from sources such as property taxes, they rely on equalization assistance — state funding calculated by total enrollment. This year, Highland is receiving roughly $7,600 per student, according to their 2020 budget.

“The temptation with all schools is the more students you take, the more money you get,” said Sofka. “There’s pressure there.”

Despite a legal license for 150 students, Highland Free School has remained small.

“Nicholas has always kept true to his beliefs,” said Megon Beeler, whose children, and now grandchildren, have been attending Highland since 2001.

“He looks out for his school, looks out for his business,” Beeler said.

Like the homemade playground, which Sofka referred to as, “the discards of America,” Highland Free School has been an exercise in resourcefulness since 1970.

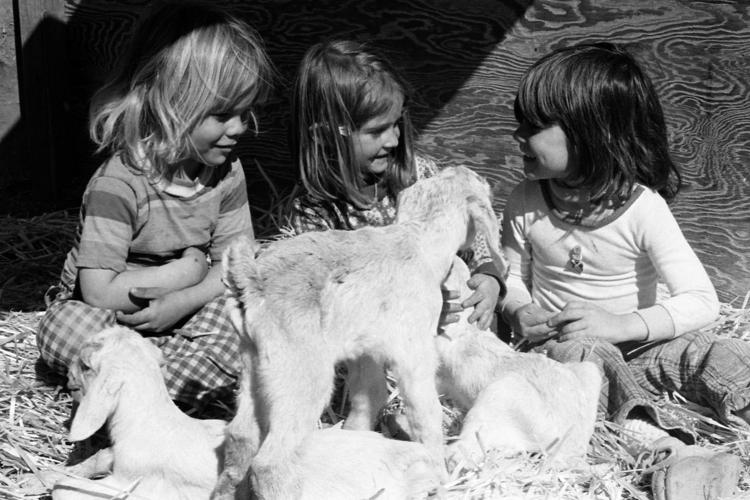

A look inside Highland Free School in 1978. Today, its students commute to the school from all corners of the city.

Arriving to Tucson in his mid-20s, a recent business graduate with dreams of alternative education, Sofka found a small Catholic parish in Barrio San Antonio. The midtown neighborhood is bordered by Arroyo Chico and Broadway on the north, Kino Parkway on the east, Park Avenue on the west, and Aviation Parkway on the south.

“I found out they were only using it two hours a week,” said Sofka, “and the rest is history.”

In 1970, he began renting the parish building for $25 a month. Monday through Friday, Sofka would operate a school of 20 to 30 students; on the weekend, he’d replace the Madonna and cross on the wall for Mass.

The Barrio San Antonio community had wanted a local church and, after years of fundraising, purchased the land in 1949. The Roman Catholic Diocese of Tucson reportedly paid $3,000 for a barracks from Fort Huachuca to be moved onto the property, becoming the area’s first chapel.

By the late '70s, Sofka said the parish was struggling. In 1980, when the Diocese put the property up for sale, a close friend of his was able to purchase it. Four years later, she officially gifted the property to Sofka, "for the consideration of love and affection," according to the deed.

For its first 30 years, Highland wasn't free — it was a private school with a flexible tuition.

"I never let money be a deciding factor," said Sofka, who would accept volunteer hours from parents in lieu of payment.

In 2000, six years after charter schools were approved by the Arizona legislature, Highland made the switch to charter.

Despite fears that becoming public could come at a high cost, Sofka discovered it actually paid. For the first time, Highland had stable funding and Sofka was approved for loans to expand the facilities.

Now like the make-shift church that preceded it, the school draws people from across Tucson. Many of Highland’s students commute to the school from all corners of the city.

Beeler has driven her children from as far as Sahuarita to attend the charter school. For almost 20 years, Murphy drove from Red Rock to teach every day.

Others, like Sonora Buck-Shannon, who attended Highland from around 2006-2012, were neighborhood locals.

“We’d go on walks by the school when we were younger,” said Buck-Shannon. “My mom loved it, just loved the way it looked.”

When she started at the charter school in kindergarten, Buck-Shannon said she didn’t realize how special it was.

“When I got older, I’d compare experiences with friends from other schools,” she said.

Unlike at her friends’ schools, bullying was never an issue at Highland. Sofka has maintained an anti-violent environment at the school.

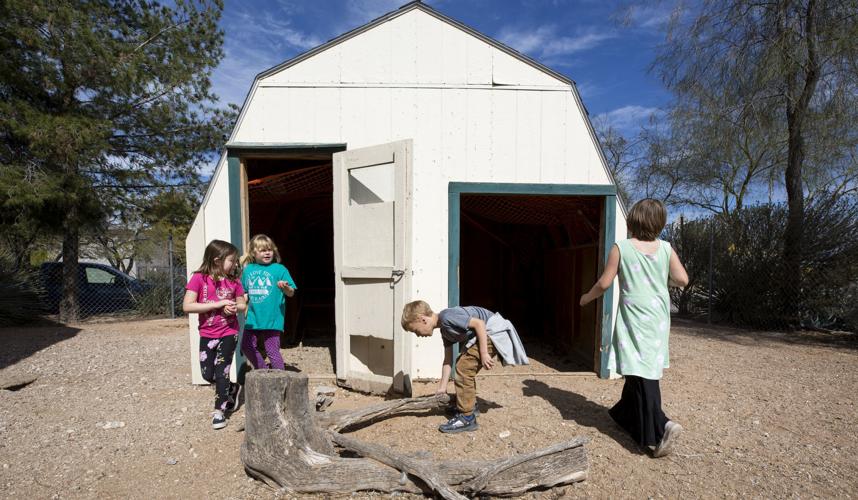

Padraic Sax, 7, runs around the playground during lunch at Highland Free School, 510 S. Highland Ave.

“You can’t solve a problem with force and intimidation,” said Sofka. “We have control there, but we teach the students to control themselves.”

Sofka believes with self-control, students can achieve anything — a critical component for a school practicing self-paced curriculum, which champions multi-grade classrooms and allows students to learn at their own pace.

Recently starting college at the University of Arizona, Shannon-Buck was nervous her history of alternative education would set her behind.

“Highland focused on learning for yourself, taking your own initiative, so sometimes I thought I’d be a little lacking,” she said. The opposite has been true, however. Shannon-Buck has found herself ahead of many peers and even on the UA dean’s list.

Highland has also earned academic recognition — in 2019, the Arizona Board of Education issued Highland Free School an A on its report card, placing it among the top 28% of schools in Pima County.

“Every single year there is an improvement,” said Teresa Rodriguez, who’s taught at Highland since 1991. “I’m just looking forward to what the future brings.”

As the school embarks on its 50th year, it’s already forged a legacy: over 30 goats and many chickens have been born on the property, annually planted Christmas trees now shade the playground from heights of up to 45 feet, and the children of alumni are following in their alternatively educated footsteps.

What started in 1970 as, “a bunch of hippies wanting to change the world,” in the words of Sofka, has become almost 50 years of successful learning, ingenuity, and adventure. At age 76, waking up to his dream every day, Sofka can’t imagine ever doing anything different.

Teacher Teresa Rodriguez and student Adam Montano looked at an insect on the playground in 2000. The school has converted recycled materials into playground equipment.

Students search for recently laid eggs in Highland Free School’s barn at 510 S. Highland Ave., in Tucson, Ariz., on Feb. 19, 2020. Highland Free School, which opened in 1970, is celebrating its 50th anniversary.

Paul Lindsay, Michelle Whipke and Jason Molina visit with baby goats at Highland Free School, Tucson, in 1975.

Students at Highland Free School, Tucson, in 1978.

Nicolas Sofka, center, with students and teachers on the playground at Highland Free School, Tucson, in 1994.