It was about 9 a.m. on Oct. 5, when the call came: Word was that immigration officials would be releasing hundreds of families in Southern Arizona over the weekend. It was Friday.

A few hours later, following a national phone conference with social-service organizations and conversations with local Immigration and Customs Enforcement officials, Teresa Cavendish of Catholic Community Services got a confirmation. More than 700 parents and their children recently apprehended by the Border Patrol — at least 470 in Yuma and 285 in Tucson — would be released in less than 24 hours.

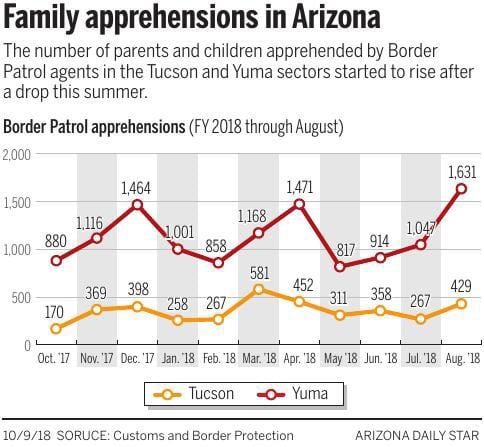

Since 2014, the number of Central American families, particularly from Guatemala, coming across the U.S. southern border has been rising. They either cross the border and turn themselves in to the Border Patrol or present themselves at a port of entry to seek refuge. Recently, they’ve been seeking agents in larger groups, while more families are told to come back later or made to wait longer to be processed at legal ports of entry.

The larger groups have meant that Border Patrol sectors such as Yuma’s are working at over capacity, officials said.

Yuma can keep up to 350 people in custody , whether that’s a family or single adults, said Henry Lucero, ICE field office director in Phoenix, “and over the last few weeks they were operating above capacity with some days 400 to 450 in custody.” Yuma had also started to transfer people to the neighboring Tucson sector, risking filling another sector.

The situation in Yuma, he said, is what ultimately sparked the larger releases to Tucson, Yuma and Phoenix offices. Customs and Border Protection turns people over to ICE after they’ve been processed, which in turn decides whether the person will be released or detained as they go through the immigration process.

In Tucson, Casa Alitas, run by Catholic Community Services, and The Inn Project of the Methodist Church normally receive these families, but they have a combined capacity of 85 people, Cavendish said. The Yuma Refugee Ministry can house about a dozen more.

The release of hundreds meant they couldn’t do it alone. They needed help.

Amy Almquist plays with a group of migrant children. “I’m better here than at home,” says Dani, a migrant who came from Guatemala with her 4-year-old daughter. “We have clothes, shoes, food. Thank God for those who are looking after us.”

“Let’s do it”

When church member Paul Flores picked up the phone he was only asked, “What’s the capacity at your church?” Catholic Community Services didn’t know for how long it would need the space, he said, or exactly how many people it would end up receiving, only that the families needed a place to stay as they made travel arrangements.

Church officials asked the Arizona Daily Star not to name the parish because they want to avoid attention. What they were doing, they said, is what they are called to do as people of faith.

Due to limited family detention space, families who pose no security risk can be released into the community, often with an ankle monitoring bracelet and a notice to appear before an immigration officer.

Lucero said ICE has the capacity to process about 120 family members a day, but the Border Patrol in Arizona was apprehending near 200, which led to a backup. “We couldn’t continue to do business as usual.”

That same night, Flores called the church leadership to ask whether the church was able to help.

“Let’s do it,” the priest said and he got right to work. He made a to-do list: set up tables, clean bathrooms and lockers and move furniture.

He texted some of the church’s regular volunteers, and by Friday night 15 had committed.

Before the first group of about 24 people arrived Saturday afternoon, the church had 140 cots from the Red Cross set up, a cafeteria area, a travel station, a medical area, tables with donated clothes and shoes sorted by gender and sizes, and toys. Catechism rooms became dorms and a youth activity classroom a pantry.

A video from the Guatemalan Consulate gives instructions to migrants in Spanish, but many indigenous Guatemalans speak very limited Spanish, experts say.

Flores created two videos, one for volunteers and one for the migrants. In it, Sebastian Quinac, a Guatemalan Consulate employee, explains the migrants’ rights and responsibilities.

Quinac tells them to keep the ICE form that tells them when and where they have to show up in a safe place. They must make sure to keep their appointments, he says, and to be sure not to remove an ankle monitoring bracelet if they have one. Not showing up or removing the bracelet can lead to their deportation or even to criminal charges. He talks about the importance of having a lawyer.

And he tells them about the community that is welcoming them, volunteering their time and not getting paid.

Volunteer Joan Kaltsas, a self-described bossy 74-year-old, arrived Saturday morning.

Nobody had any practice doing this kind of work on this scale, she said, so she started to walk around to see if she “could make some order of the chaos.”

She put out a call for towels and helped set up a laundry system.

Often the clothes the migrants are wearing are the only things they have. So when the person exits the shower with their dirty clothes in hand, there’s someone who gives them a plastic bag and a number.

Other volunteers stop by throughout the day to take the clothes home to wash and bring back before the families leave.

A male volunteer had just returned from the bus station. He had taken a migrant family there to head for Virginia, but they couldn’t leave, he told Kaltsas, because of Hurricane Michael.

“That’s a new development,” Kaltsas said, “east of Houston all transportation is shut down.”

Before she could continue, another woman stepped in. “I just brought all these clothes and brushes. What do you need?”

The support was overwhelming, Kaltsas said, with people arriving daily who heard about what was happening from Facebook or through a neighbor, asking, “What can I do? How can I help?”

Teachers and students spent their fall break sorting clothes and playing with the kids. Doctors left football games to tend to the sick. People stopped by in between work meetings.

Kaltsas tells them, “I can’t pay you, but I can give you a hug.”

By last Sunday, the church was hosting about 45 people. By Monday, more than 100 were there, along with dozens of volunteers coming and going.

Migrants line up for help with phone calls and travel assistance. Many have friends or family in areas to the east, but Hurricane Michael delayed their travel.

”One day, God willing ”

These Central American families leave their countries for a variety of reasons. Some flee gang violence or abusive partners. Others try to escape generational, entrenched poverty worsened by severe drought and fields that don’t yield enough to feed their families. Often, there’s no single cause.

Regardless, all see the United States as an opportunity to make a better life for themselves and their children — those who come along with them and those left behind. Most have friends or relatives in places like California, Texas and Florida with jobs and promises of better lives.

Dani got together with a man when she was 15, but he left her as soon as her daughter, now 4 years old, was born.

She lived with her mother in the Guatemalan state of Huhuetenango in a small wooden home with no electricity, she said. They farmed. Some days they ate, others they didn’t.

She asked that her full name not be used because her immigration case is pending.

There was even less money to pay for medical care. Her mother has a hernia, but they can’t afford the operation, she said, and that’s the main reason why she’s here. They know all too well the potential consequences of forgoing treatment. Her 4-month old niece died a few months ago, she said, due to a gastrointestinal infection.

The trip north is hard, she said, holding back tears. Her cousin borrowed 29,000 quetzales from a bank, roughly $3,800, for the smuggler. It has to be repaid in a year. The first payment is due this month.

They traveled by bus several days with little to eat, and walked a day or two, she doesn’t remember how long, to the Arizona desert near the Lukeville Port of Entry, where agents apprehend large groups. She had to carry her daughter part of the way because there were animals and a lot of thorny plants.

Back in Guatemala, Dani said, when her daughter asked for dolls and clothes, she would tell her, “My love, I don’t have anything to give you, but one day, God willing, we will have the opportunity to go north to work and we are going to be much better.”

Along the way, she said, her daughter started to complain. “‘Didn’t you tell me that one didn’t suffer up north? I’m hungry,’ and I didn’t have anything to feed her.”

Migrants the Arizona Daily Star spoke with described intense cold and overcrowding inside Border Patrol stations. They lost track of time, they said, because the lights were always on. Most complained about the frozen burritos they’re served.

Over four days, Dani and her daughter were in custody at different locations. She said all her daughter had was fruit juice, because she couldn’t stomach anything else. And when she asked if they had anything else, like rice, Dani said some agents would respond, “If you want to eat, you should return to your country.”

Not everyone was rude, she said.

“Some agents were kind.”

Judy Collins hands a handful of tortilla chips to a young boy in the food line as volunteers help hundreds of migrants with the basics of food, clothing, medical assistance and temporary shelter at a local Tucson church, Oct. 10, 2018.

Friendships form quickly at the church

Over the last week, relationships were built despite language barriers.

Kaltsas doesn’t speak much Spanish, but she had the word hijos — children.

And she managed to make a new friend, a migrant mother staying at the church who helped her cut papaya.

“Brendi,” she told the woman, “papayas for ... I forgot the word for dinner ... and maybe algunas amigas,” maybe get some friends. “No, solamente yo, I will do it,” Brendi told her.

When Brendi was done, Kaltsas embraced her in a tight hug to show her appreciation.

“We can’t communicate,” she said, but their willingness and mindfulness is enough.

Everyone wants to help. Dani, the Guatemalan mother, had a blister from mopping. It was her first time using a mop, she said, because back home they only have dirt floors.

Inside the converted gym, parents cradled their children. One man approached a woman to ask if she knew how to braid, pointing to his daughter’s long black hair. Their attentiveness to their children captured the hearts of volunteers.

A father and his daughter look for shoes at a Tucson church that has been converted as temporary shelter space for the dozens of families being released on a daily basis by immigration officials. Nearly 200 were dropped off Saturday by U.S. Border Patrol agents.

The first thing they do when they arrive, Kaltsas said, is to look for shoes and clothes for their kids, not for themselves.

The children and the separation of families is what worries Lorena Zarate, another volunteer, the most. She sees their tiny eyes water and their voices quiver when they use the phone to call a parent left behind.

“The little boy or little girl needs their father or mother,” she said. “Their pain is just beginning.”

But for now, they are safe and cared for at the church.

Dani said she wanted to get on her knees when she first walked in and saw the gym bustling with volunteers ready to embrace them, to say everything is OK, you are welcomed here.

“I’m better here than at home,” she said. “We have clothes, shoes, food. Thank God for those who are looking after us.”

“Many say they cry the first time they shower,” their first in weeks, Zarate said.

Children play with balls and dolls, things they lacked back home.

They’ve found new friends in one another. A group of teenage girls walked around donning party dresses and trying on high-heeled shoes and makeup. They’d met along the journey and inside the church, but looking at them you would think they had been lifelong friends.

A volunteer brought a couple of guitars, and all of a sudden they had a group playing hymns as others gathered, clapping and singing along.

As the days went by, other churches and groups stepped up to continue the work.

Regardless of political views, “This is humanitarian aid and support. Once someone sees a face of the issue, it becomes real,” said Flores, the volunteer who got the initial call.

Catholic Community Services and others used a charter bus to move about 100 parents and children out of Arizona to Texas shelters get them closer to their destinations.

But new parents and their kids are entering the system, which likely means more releases.

Tucson volunteers will be ready for them.