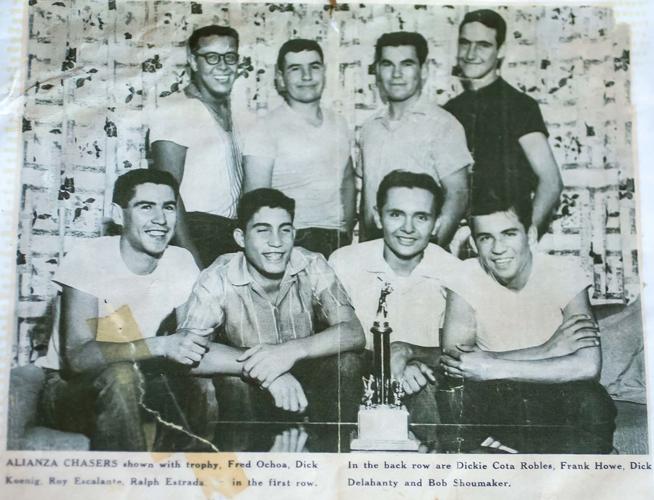

The Chasers were a band of 12 at Tucson High School in the late 1950s. Eleven were Mexican-American and one was Jewish. They were all boys and athletes. Some were considered borderline delinquents who many thought would turn out badly.

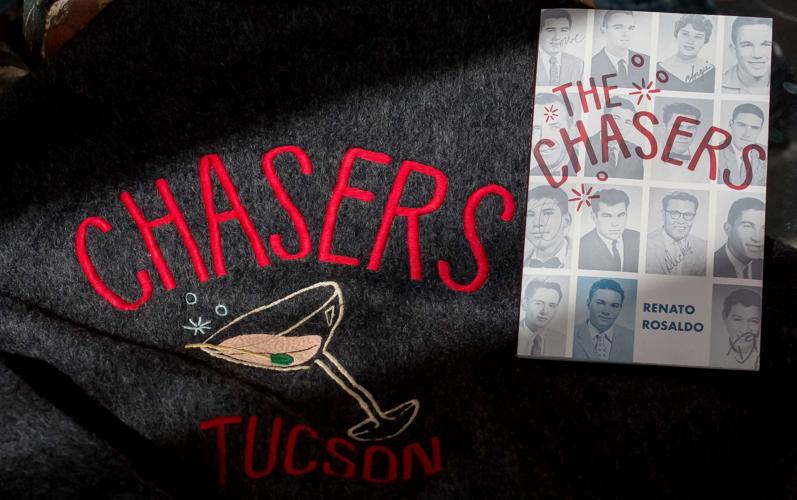

They wore custom-designed gray sweater jackets. On the back, in crimson lettering, were the words “Chasers” and “Tucson.” Between the words was a martini glass filled with champagne and an olive.

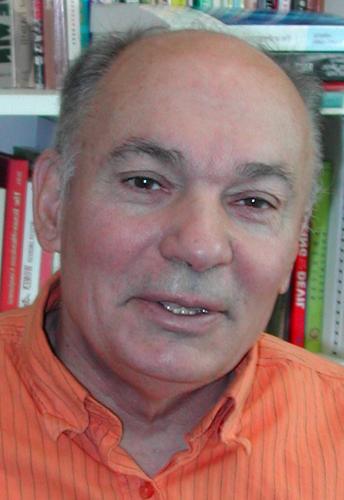

The teens chased girls, but that wasn’t all, explained Renato Rosaldo, 78, a Chaser who received a scholarship to Harvard.

“The meaning is not fixed,” said Rosaldo, of Brooklyn, New York, in a recent telephone interview.

The teens also chased beer, truths and their dreams.

Rosaldo, an emeritus professor of cultural anthropology at both Stanford University and New York University, interviewed his high school friends in recent years and wrote a prose poetry collection, “The Chasers,” which was published this year by Duke University Press.

A photo of eight of the Chasers sits on a coffee table at Frank Howe’s house. “The Chasers” is a collection of poems written by Renato Rosaldo about 12 best friends who grew up in Tucson in the 1950s. The Chasers created a brotherhood that chased girls, drinks, parties, truths and their dreams.

“Reworking the interviews into prose poetry, working to make harmony and making sure what remained was true to what they had to say was challenging,” said Rosaldo. “Arriving at the way I formatted the poems was the hardest in writing the book.”

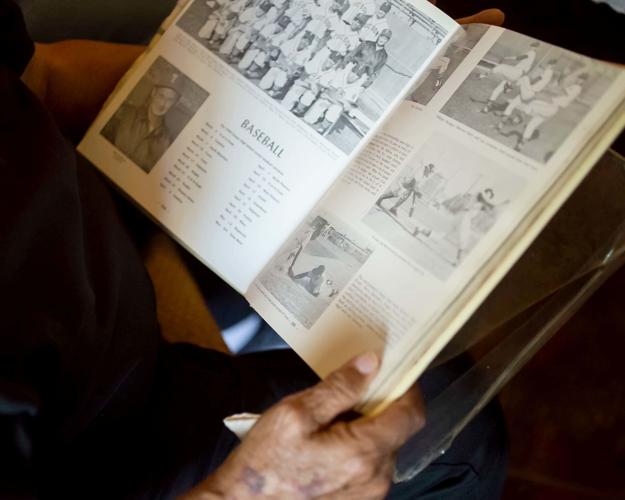

The process, which included videotaping and transcribing the interviews, took about six years. The book includes childhood experiences, stories about institutional racism in the educational system, poverty, hard work, family values and friendships among teens growing up.

When Rosaldo received advanced copies, he autographed and read the book to the Chasers. It was the “most meaningful” reading because it was the “moment of truth, looking into the eyes of the bull.” The men accepted his work as true to what they said.

“I cried when I went home and told my wife what happened,” Rosaldo said with a laugh. “I cry a lot now that I am old.”

Reunions are ongoing

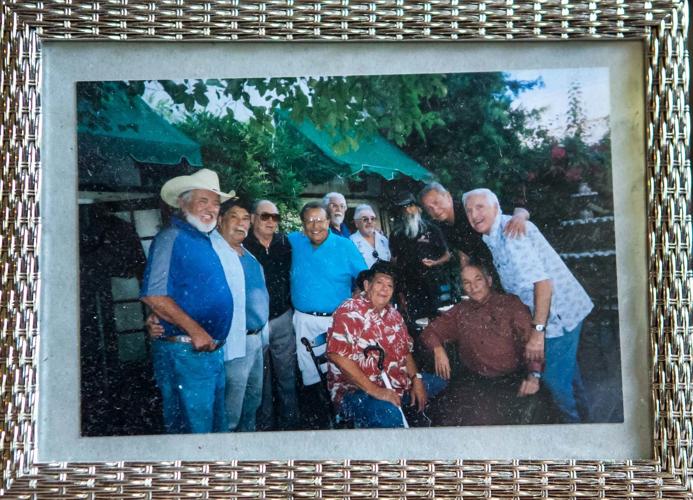

Most of the Chasers graduated in 1959 and never gathered again until their 50th Tucson High reunion in 2009. They met in the patio of The Shanty, an Irish pub north of downtown. It is a watering hole for many blue-collar workers and UA grads, professors, journalists and politicians.

Renato Rosaldo

That reunion flooded the men with memories of camaraderie, people and places they would never forget, and the importance of being a lifeline to each other as teenagers. The high school reunions have continued for the retirees and one is set for Oct. 24 at the Viscount Suite Hotel, 4855 E. Broadway.

Two Chasers, Andy Contreras, a Los Angeles supermarket produce manager, and Richard Rocha, a Riverside, California, attorney, have died.

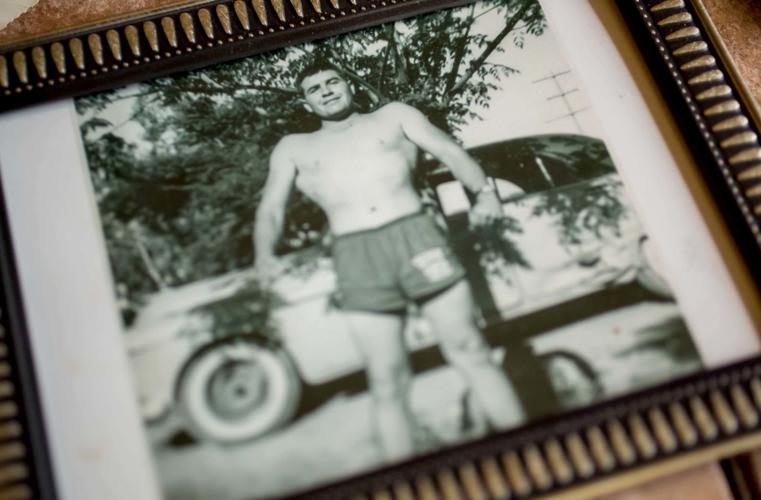

In addition to Rosaldo, remaining Chasers include Frank Howe, a Tucson Unified School District principal. He was originally from Pirtleville in southeastern Arizona, and was a farm worker as a boy, working alongside his family as they followed crops to California fields and orchards. The book starts with his story, “Walnuts,” and tells of the backbreaking work, living in a labor camp, and following crops until he was in sixth grade and moved with his family to Tucson.

“The Chasers” as seen at the 50th high school reunion in 2009. Most of the Chasers graduated from Tucson High School. Two of the 12 have passed away.

There also is Dickie Delahanty, a Tucson firefighter and paramedic who helped battle the historic Pioneer Hotel Fire in 1970, and Dickie Cota-Robles, a Southern Arizona field superintendent for a mechanical contractor.

Cota-Robles designed the Chasers’ jackets, saying he put champagne in the martini glass because he didn’t know anything about drinking. He and his cousin, Bobby Shoumaker, a neurologist in San Antonio, Texas, founded the Tucson High social club in 1956-’57.

The remaining Chasers are Louie Dancil, who left Tucson High and graduated from Pueblo in 1959. He became a businessman and shares stories of smuggling marijuana from Mexico and Jamaica into Arizona while piloting a Cessna, eventually serving three prison sentences. “I got into the trade because of the adrenalin rush and greed,” Dancil said.

Then there is Ray Escalante, an artist and Tex-Mex singer who performed regularly in Nogales, Rio Rico and Patagonia; Ralph “Ginger” Estrada, a Phoenix lawyer; Dr. Richard Koenig, a psychiatrist in East Quogue, a village in Long Island, New York; and Freddie Ochoa, an estimator in moving and storage who now lives in Pinetop.

Hiding their smarts

One close friend of the group is Angie López, who was the high school girlfriend to swim team captain Rosaldo. López became a bilingual teacher in the Sunnyside Unified School District and the owner of a religious store.

López described the Chasers as smart but said they kept it a secret because they didn’t want to look like nerds or be shamed as “schoolboys.” Those who shamed them did it because of jealousy, she said.

Rosaldo explained that Estrada taught him to carry two sets of books — one for school and one for home. The books at home he devoured, studying, learning the subjects and memorizing facts. At school he carried no books, leaving them in the locker, and no one messed with him.

Dickie Cota-Robles looks through a 1959 Tucson High School yearbook at Frank Howe’s house on October 17th, 2019. “The Chasers” is a collection of poems, written by Renato Rosaldo, about 12 Chicano best friends growing up in Tucson in the 1950’s.

The Chasers were football, baseball and basketball players and they attracted Anglo girls. Another Tucson High student, Tom King, said “Anglo boys felt jealous, wondered why you crashed their parties, didn’t know the girls had invited you,” López recalled.

She said there was loyalty among the Chasers, with members having each others’ backs.

“It wasn’t spoken, it just was,” she said.

The men look back at their teen years and can roar in laughter. Among the memories are the years they would scout homes in the wealthy El Encanto neighborhood, just west of what is now El Con Mall. Once they figured out who was on vacation, they would go swimming in their pool at night. One time, Escalante forgot his trunks and hopped in the pool in the nude. Someone called the cops. When the cops came, the Chasers ran, and the spotlight hit Escalante, who was “running across the street bare-ass naked.”

Eventually, the Chasers rented rooms and went swimming at a hotel on Tucson’s far northwest side.

Five Chasers owned wheels — three had Chevrolets, one a Mercury and one a Dodge convertible — which got the teens around town.

Another funny story landed the Chasers in jail before they were transferred to “Mother Higgins,” as the juvenile detention facility was known. They took up a challenge from “gringo” students at Tucson High to an orange fight on campus. It was the last day of school their junior year.

The group went to the Sam Hughes neighborhood and picked oranges off the trees or on sidewalks. They filled the back seat and trunk of a Chevy and returned to school.

The oranges went flying throughout the campus and in the hallways. But the Chasers were the only ones busted. They were released to their parents, and authorities let the parents deal out the punishments. Some were grounded, some were not.

Rosaldo recalled portions of his childhood. After one year of college, his father, also named Renato Rosaldo, migrated to Chicago, received his doctorate at the University of Illinois, and married Betty Potter, an Anglo woman. Later, he taught Mexican literature in the Spanish Department at the University of Wisconsin. Rosaldo liked growing up in Madison with his friends and the snow, playing sports and being a good student. He was also pained when he started forgetting Spanish, explaining that a part of him died.

An old photograph of Frank Howe in High school at Frank Howe’s house on October 17th, 2019. “The Chasers” is a collection of poems, written by Renato Rosaldo, about 12 Chicano best friends growing up in Tucson in the 1950’s.

Then, in the 1950s, he moved to Tucson with his family when his dad was hired as head of romance languages at the University of Arizona. Rosaldo made a new friend, and one day he heard the friend call “Mexicans dirty.” The friend looked at Rosaldo and told him that he didn’t mean him.

But the words struck a chord and Rosaldo told himself he had to re-learn Spanish and become Mexican-American. He remembered conversations with his grandmother, Mama Emilia, while she cooked chilaquiles and arroz con pollo. It took time, but his Spanish eventually started to flow.

He later joined the Chasers, teens who became his protectors and lifelong friends.

Dickie Delahanty, left, Frank Howe, a photograph of Richard Rocha, Angie López, Louie Dancil and Dickie Cota-Robles pose for a portrait at Frank Howe’s house on October 17th, 2019. “The Chasers” is a collection of poems, written by Renato Rosaldo, about 12 Chicano best friends growing up in Tucson in the 1950’s.

A sweater-jacket, designed by Dickie Cota-Robles and wore by all 12 Chasers in the 1950’s, woren by all 12 Chasers in the 1950’s, rests on a table during a portrait at Frank Howe’s house on October 17th, 2019. “The Chasers” is a collection of poems, written by Renato Rosaldo, about 12 Chicano best friends growing up in Tucson in the 1950’s.