The Tuesday before Thanksgiving, while most were preoccupied with holiday preparation or tying up loose ends at work, a group of Tucson middle schoolers was busy inventing.

At first glance, their task seemed simple: Find a new use and user for an everyday object. But upon deeper look, it's not so easy to reimagine something so engrained in one's mind.

The items included a glass jar, a belt, a tissue box, a bottle of dish soap and the plastic tub everything came packaged in.

But 20 minutes later, the items had been transformed into a worm counting jar for fishers, a belt sheath to hold gardening shears, a tissue holder for football players' face masks, a shower-stream soap dispenser, and a transparent box to protect student artwork.

Watch now: Invention education teaches the ways inventors find and solve problems. Students use their inventiveness to try to fix a problem that affects someone in their life. Carden of Tucson is the only school in Arizona to teach invention education in every grade. Video by Caitlin Schmidt, Arizona Daily Star

This is invention education, and Carden of Tucson, a small charter school on the city's north side, is the first in the state to teach it at every grade level.

Invention education teaches the ways inventors find and solve problems. Students who participate become more engaged in their learning, more inclusive in their thinking and are better prepared for a future of uncertainty and rapid change, according to InventEd, a Lemelson Foundation initiative. The foundation aims to support future generations of inventors to create a better world.

Carden leaders hope that by advocating for this type of education — which has demonstrated success in Connecticut, Georgia, California, Michigan, Mexico, China and other places — it will spread beyond their school and into the community, state and region.

Solving problems, thinking critically

Carden's invention education curriculum is modeled after the Connecticut Invention Convention's program. Teachers help students develop creative ways to solve problems, as well as critical thinking skills, by learning about invention and entrepreneurship.

The curriculum was brought to Carden three years ago by Bri Livingood, the school's assistant director and a middle school teacher. Livingood learned about this type of education while teaching in Massachusetts, and also works as school and community outreach coordinator for Connecticut Invention Convention.

"The really exciting part about all of this is the process that our students get to go through as far as identifying a real world problem that's meaningful to them and then coming up with a solution to it," Livingood said.

What's Working

Even during pandemic, Tucson nonprofit advocates educational opportunities for undocumented students

Successes, she says, include a "first grader solving a genuine problem her little brother has or a sixth grader identifying a problem for a grandfather with Parkinson's and creating a meaningful solution to that."

When she began teaching at Carden, she pitched the idea of bringing invention education to every grade. School Director Eugene Moore jumped at the idea.

"This just gives students an opportunity to think about everyday life, not just for this project but everything they do in life," Moore said. "It's the little things that will make their daily lives that much easier, whether it’s a way to carry pencils in a backpack without breaking them or something else."

Carden has partnered with the Lemelson Foundation, MIT, Raytheon, The Henry Ford museum and others to help and support students in their invention education.

During the school year, students learn how to use their inventiveness to make existing items better and solve meaningful problems. In April, students will share their inventions in a competition judged by experts in technology and innovation.

During the first few months of the year, students learn to identify inventions that are all around them. Livingood and other teachers talk about the process of creating and improving and how long it can take to develop something that sticks.

"It does take brainstorming, and those are muscles you really have to work," she said.

In class Tuesday, Livingood reminded students that Thomas Edison went through 1,000 versions of the lightbulb before developing one that actually worked.

"Part of why I love it is because I never saw myself as a science person … but invention education made the engineering and STEM process so accessible to me," Livingood said, referring to science, technology, engineering and math instruction. "Because I can identify a problem, I can come up with a solution. But if you tell me to come up with a schematic, and let's look at blueprints and talk about the design process, I got none of that."

Invention education makes the process of creating and innovating accessible and inclusive, opening up those skills for students of all kinds, she said.

"You see that in their presentations," Livingood said. "Some kids might be more inclined to make a really beautiful invention and the aesthetics of it maybe are not as detailed, but you can appeal to the art student, you can appeal to the kid who is passionate about a problem, you can appeal to a kid who cares about a historical issue."

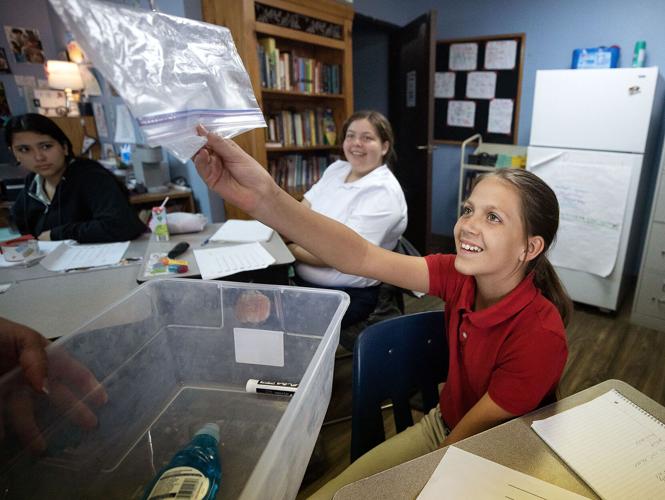

During Tuesday's class, students used a process called SCAMPER to help them brainstorm a new use for their item. SCAMPER — an acronym for Substitute; Combine; Adapt; Modify, magnify and minify; Put to another use; Eliminate; and Revere — allows students to pick and choose from the list as they think about how they want to create something new.

Livingood told the class to start by identifying who they want the user of the product to be, then move onto developing something that would be useful for that person. Students had 20 minutes, and while the room was silent for the first few, it soon came alive with energy as they collaborated, shared and challenged one another.

They presented their prototypes or schematics at the end and voted on a winner. The top two vote getters were the worm counting jar for fishers and the transparent protective display for art teachers.

"Anyone can have inventiveness in them," Livingood said. "And it's a skill set you can use in all aspects of life."

Hoping other schools will offer it, too

Carden hopes to offer invention education over the summer to any child in the school's neighborhood, regardless of enrollment status, during a free two-week camp.

Livingood and Moore also want to share the program with the broader Tucson community in hopes that other parents will want their children to have this experience and schools will want to join in.

"A more regional push would be the next step," Moore said. "In Southern Arizona and wherever we can spread the word."

Livingood is in talks with a teacher in Vail about developing a similar program. She also met educators from Yuma and the Phoenix area at a national invention convention conference, so more statewide involvement might not be far off.

In the meantime, she's been working to gain community momentum, build partnerships and find financial support for the program. They're working with the University of Arizona's College of Engineering to teach students about materials they'll be using and how they're made and used.

Carden's invention convention, April's culminating event, will be held at the Southern Arizona Arts and Cultural Alliance's Catalyst space at Tucson Mall.

"Our students' work will be on display for other people to see, not just our school. We'll have an open house, and we'll have about 50 judges there looking at students' projects," Livingood said.

Students will have a 3D printer to work with and are learning to draw and create schematics online.

The school has also partnered with the U.S. Patent and Trademark office and the Office of International Intellectual Property Enforcement to help students understand the value of their intellectual property and the patent process.

Students in younger grades also undertake family based STEM projects, with materials sent home for parents to work on with their kids. Last quarter it was an instrument and now it's an article of clothing.

"I think sometimes parents get turned off from, 'I'm not a scientist.' Especially our demographic," Livingood said of the school's population. "We're low-income, we're in the middle of a trailer park and not many of our parents went to college."

But the home-based projects allow parents to participate in the learning process, empowering them, she said. Parents will also be involved in the invention process, with all grades except kindergarten set to participate in April's convention.

"They will be presenting and going through the whole thing, like an elevator pitch," Livingood said. "We have quite a rubric of what our judges are looking for to ensure an original idea."

Builds self-confidence, communication skills

Invention education is also a big deal for teachers, Livingood said.

"It's a big ask of teachers to do something that's not just in a textbook. It's more free-thinking, and it can be a little chaotic sometimes," she said. "Our teachers are to be commended for recognizing something really good for their students and wanting to take on the challenge of providing them with something above and beyond."

Holly Nichols teaches second and third grade at Carden and said invention education helps teachers learn more about their students.

"I saw a different side to them that I didn't know I would see," she said. "It brought out different qualities in the students, and I had no idea it was going to do that."

It's also fun, for students and teachers.

"I feel like they don't look at it as science, they look at it as solving a task together and being aware of what other people are thinking," Nichols said. "They're so hungry to just focus on their idea and learn the process of creating an invention."

Nichols enjoys watching students work to solve a problem for themselves or someone close to them while also applying educational standards from other disciplines, including math, science, history, language skills and research.

"I've seen it build self-confidence and communication skills," she said. "The process is definitely what I enjoy the most. Parents love product, teachers love process. Process is our paycheck."

Livingood and others are looking forward to seeing where invention education takes them at Carden and beyond. She's hopeful the summer camp will be a good demonstration that the program doesn't have to be a yearlong experience, but can also be sized to meet needs.

"The cool thing about it is it can be an after-school program, it can be a camp," Livingood said. "It's best probably activated in the classroom, but you can learn anywhere and students can engage anywhere."