From her father’s beige-stuccoed mobile home, Genesis Hollman has watched two families move into the trailer next door on a rent-to-own contract.

And she has watched both of them leave the small south-side mobile home park in frustration after learning the landlord didn’t have proper title to the trailer.

“They sell them and sell them and sell them,” says Hollman, 26.

Housing advocates say it’s a familiar story in Tucson, where widespread poverty and a lack of affordable housing creates an environment ripe for victimization: Too many mobile home park owners are dealing trailers without proper paperwork.

“They’re selling these things and half the time, they don’t have the title because it’s been abandoned by the original owners,” says Joe Scelza, vice president of the Arizona Association of Manufactured Home and RV Owners. The group advocates for mobile home park residents who own their trailers and rent the land underneath.

For prospective homebuyers who can’t afford a site-built home or who don’t have the credit for a mortgage, rent-to-own contracts on mobile homes — in which part of the monthly rent goes toward buying the trailer — offer a rare chance at homeownership.

But rent-to-own contracts are often full of loopholes, legal advocates say. Unscrupulous sellers collect on a trailer for months, then find a pretext to evict the buyer and resell the trailer. Other times the buyer finishes paying, only to find that the seller never actually owned the trailer.

“It’s selling the American dream to poor people,” says Beverly Parker, managing attorney with Southern Arizona Legal Aid in Tucson, who has seen this scenario play out repeatedly. Sellers “don’t think they’re doing anything wrong. It’s just business.”

PRETEXT FOR EVICTION

Under the Mobile Home Parks Residential Landlord and Tenant Act — which applies to mobile home residents who own their trailer and rent the land beneath — a tenant can be evicted on the next notice after receiving three notices about the same problem or four notices about different problems within one year. That’s a fairly easy standard to meet if a landlord is looking for problems, advocates say.

Arbitrary enforcement of park rules — and the targeting of vocal tenants — is hard to prevent through legislation, says Rich Zettlemoyer, president of the mobile homeowners association.

A clause in the mobile home landlord-tenant act puts the burden on the landlord to prove his or her actions were not in retaliation if an eviction comes after certain actions, like a tenant reporting code violations.

But in the justice courts, where evictions are heard, the burden of proof often falls on tenants, who rarely bring legal representation, says Stan Silas, senior staff attorney with Community Legal Services, Inc., in Phoenix.

“There aren’t enough attorneys out there willing to help them do this,” he says.

A 2005 report on eviction proceedings in Maricopa County, organized by the Phoenix-based William E. Morris Institute for Justice, found that most cases were heard in less than one minute — and many only took 20 seconds. The study found that 87 percent of landlords came to court with legal representation, and no tenants did.

The study led to 2009 reforms standardizing eviction proceedings, says its supervisor, Ellen Sue Katz, an attorney with the Morris Institute.

“The rules, if followed, would make things much better for tenants,” Katz says.

Last year, more than two-thirds of all eviction cases — not just mobile home cases — were ruled in favor of the landlord in the Pima County Consolidated Justice Court, says Doug Kooi, court administrator. That’s about 10,000 of the 14,300 eviction cases heard in 2013.

Justice courts are presided over by justices of the peace, elected officials who do not have to be attorneys. Sometimes filling in are judges pro tempore — part-time, appointed justice officers who also do not have to be attorneys.

Many judges are diligent, Legal Aid’s Parker says, but “if your judge is not a lawyer, it’s hard to argue the law.”

Justices of the peace “tend to believe nonpayment of rent trumps everything,” says Silas, the legal advocate. “Justices might not consider the conditions the tenant is living in, or that landlords sometimes fail to meet their contractual and statutory obligations, as well.”

Landlords typically lead the training sessions on landlord-tenant law for justices, he says, and training on mobile home-specific legislation has been minimal.

“Most of the time,” he says, “the tenant is the one swimming upstream.”

TENANT HAS FEW OPTIONS

To legally deal mobile homes, park owners must be licensed by the Arizona Department of Fire, Building and Life Safety. But unlicensed dealing of mobile homes is common, says Debra Blake, deputy director of the department’s Office of Manufactured Housing.

The office has issued 87 cease-and-desist orders statewide to unlicensed dealers since 2008.

“There’s a lot of illegal sales going on in parks,” she says. “It’s a big problem.”

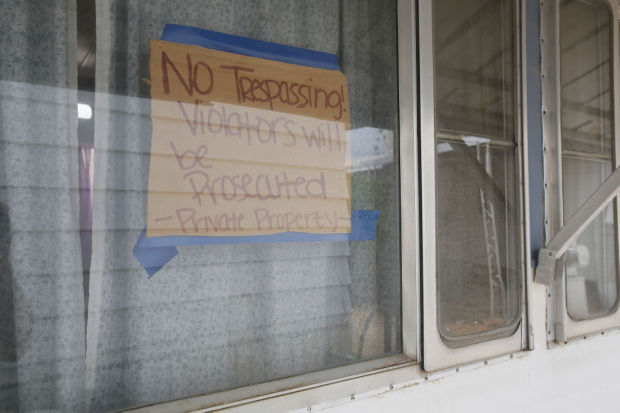

At Colonial Mobile Home Park on Tucson’s south side, where residents have complained that the owner sells trailers he doesn’t own, property manager Elizabeth Casillas says the park lacks titles to some trailers for sale because they were abandoned. She says tenants who buy them are told up front that they’ll need to get titles themselves at the Motor Vehicles Division.

Jim Stagner, who owns Colonial and at least three other mobile home parks in Tucson, did not respond to calls seeking comment about selling untitled trailers.

A seller must acquire a clean title before he or she can sell a mobile home, says Mike Parham, legal counsel for Manufactured Housing Communities of Arizona, a lobbying group representing park owners. If a trailer has been abandoned in a mobile home park, the park owner can obtain a bonded title through the Motor Vehicles Division or hold a landlord-lien sale — that is, offer the trailer at a public auction where most likely, the landlord will be the highest bidder and will receive the title from the MVD.

Those who unknowingly purchased an untitled mobile home can sue the landlord or file a consumer fraud complaint with the attorney general’s office. Their best bet would be to persuade the park owner to get the title and have it transferred to the buyer, Parham says. But that can take years — and is unaffordable and unrealistic for many people scrambling for stable housing, Legal Aid’s Parker says.

“You’re talking about people who don’t have access to justice because they can’t afford it,” she says.

No one tracks how often would-be buyers get snared in rent-to-own deals gone wrong, but based on the number of victims seeking help at Southwest Fair Housing Council, “I’m gonna say it happens on a daily basis,” says Evelia Martinez, project manager at the Tucson nonprofit.

ABANDONED TRAILERS

Unscrupulous landlords and property managers have incentives to get tenants to abandon their homes: Abandoned trailers can be revenue streams.

Tenants who own their trailer on rented land can find themselves in an impossible position if they want to leave: Relocating a trailer typically costs $3,000 to $5,000, assuming it’s is in good enough condition to be moved.

The state offers mobile home relocation assistance, but many owners have no place to move their trailer even with that help. That’s because newer mobile home parks often have rules against accepting trailers of a certain age or condition, so costly rehabilitation may be required to secure a new space.

Often, just abandoning their trailer is the best option, especially if they can’t find a buyer approved by their landlord, can’t continue to pay their space rent or utilities, or can’t afford repairs to make the place livable.

This year, the Arizona Association of Manufactured Home and RV Owners opposed a bill — written by the lobbying group for mobile home park owners, Manufactured Housing Communities of Arizona — that legal advocates say would have made it easier for landlords to declare a trailer abandoned if the owner was absent for 30 days and rent was due for 30 days.

“Under this bill, a park owner has total discretion to claim a home is ‘substantially’ damaged and then remove or demolish a damaged mobile home without court order and with no liability. The park owner could have caused the damage and still can use these provisions,” Katz, of the William E. Morris Institute for Justice, wrote in a email to legislators considering the bill.

Susan Brenton, executive director of the Manufactured Housing Communities of Arizona, says the legislation sought to put in writing how abandonment has been handled for decades, and it would have given residents at least 77 days after the landlord filed for abandonment to pay up and reclaim the trailer.

“This is how it’s been done for the last 20 years and it’s worked,” she says.

The bill did not make it to the floor this session and Brenton says the board of the lobbying group will meet this summer to decide whether to pursue it next session.

RENT-TO-OWN abuse

When Pamela Schmidt put down money on a 1957 Flamingo model in the midtown Covered Wagon Mobile Home Park, the blue-and-white trailer was showing its age. In late 2012, a busted sewer line sent raw sewage seeping up from the ground. Since she had already signed a rent-to-own contract, park managers said it was her responsibility to repair it, which she couldn’t afford. To use her toilet, she disconnected it from the broken pipe and let the waste fall onto the ground.

But to Schmidt, 48, the trailer had the makings of a home. After she put down $1,500 in a rent-to-own arrangement, property manager Jeff Wehage repeatedly delayed handing over the title, she says. (Wehage no longer works for the property management company, office employees say.) Schmidt later realized that the photocopy of the title he’d given her had the name of a deceased woman on it.

She says she was billed thousands of dollars for supposed damage to an old awning that fell down and for late rent payments, which she says was due to confusion over what she owed and the rapid accumulation of late fees. She wanted to sell the trailer in order to pay off her debts and stop the late fees, but without the title, she couldn’t.

Schmidt was evicted from her space in February 2013 for lack of rent payment. Moving her trailer to a new park was not an option, because in the decades since it was installed, a building was erected just a few feet in front of the trailer hitch.

The landlord deemed her trailer abandoned after the eviction, and Schmidt says all of her personal belongings were removed from the trailer’s storage shed.

“So much sentimental stuff that is gone,” she says.

Covered Wagon mobile home park owner Scott Greene — who owns at least five parks in Tucson — did not respond to calls and messages left with his office staff seeking comment.

Schmidt has filed a complaint with the state attorney general’s office, but hasn’t heard anything. She says she has little hope of getting her money or belongings back, let alone the run-down trailer she bought.

“I really don’t know how to deal with all this,” she says. “I feel like I was completely taken advantage of. There’s nowhere to turn to because I don’t have the money to fight it.”