A group of scientists, including one from the UA, has new findings suggesting the Antarctica’s Southern Ocean — long known to play an integral role in climate change — may not be absorbing as much pollution as previously thought.

The old belief was the Southern Ocean pulled about 13 percent of the world’s carbon dioxide — a greenhouse gas that contributes to climate change — out of the atmosphere, helping put the brakes on rising global temperatures.

To reach their contradictory conclusion, the team used state-of-the-art sensors to collect more data on the Southern Ocean than ever before, including during the perilous winter months that previously made the research difficult if not impossible.

Some oceanographers suspect that less CO2 is being absorbed because the westerlies — the winds that ring the southernmost continent — are tightening like a noose. As these powerful winds get more concentrated, they dig at the water, pushing it out and away.

Water from below rises to take its place, dragging up decaying muck made of carbon from deep in the ocean that can then either be released into the atmosphere in the form of CO2 or slow the rate that CO2 is absorbed by the water. Either way, it’s not good.

The Southern Ocean is far away, but “for Arizona, this is what matters,” said Joellen Russell, the University of Arizona oceanographer and co-author on the paper revealing these findings. “We don’t see the Southern Ocean, and yet it has reached out the icy hand.”

Oceans, rivers, lakes and vegetation can moderate extreme changes in temperature. Southern Arizona has no such buffers, leaving us vulnerable as average global temperatures march upward.

“Everybody asks, ‘Why are you at the UA?’” Russell said about studying the Southern Ocean from the desert. She said the research is important to Arizona and the university supports her work.

Making measurements

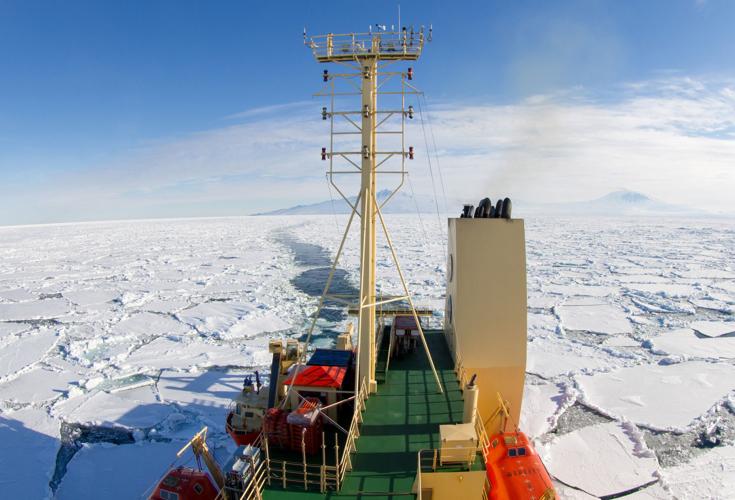

The Southern Ocean is a formidable place, especially in winter. Winds can howl at nearly 100 mph, churning waves that can surge 80 feet high. The temperature dips below freezing for prolonged periods.

“Very few people who have a sane view of the world go down there in winter,” said Rik Wanninkhof, an oceanographer from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and one of the paper’s co-authors.

For this reason, scientists know less about the Southern Ocean than the rest of the world’s oceans. What they do know is mostly limited to surface CO2 levels in the summer, when it’s safer to take measurements by ships with researchers aboard. Shipboard sensors that directly measure CO2 are the accepted scientific standard in these types of studies.

Understanding CO2 levels within the air, land and sea and how it is exchanged between the three is necessary for making more accurate future climate predictions.

To fill the gap in knowledge, Russell and her team have deployed an array of cylindrical tanks, called floats, that collect data on carbon and more in the Southern Ocean year-round. Russell leads the modeling component of this project called Southern Ocean Carbon and Climate Observations and Modeling, or SOCCOM.

The floats drift 1,000 meters below the surface. Every 10 days, they plunge a thousand meters deeper, then bob up to the surface before returning to their original depth.

For three years, 35 floats equipped with state-of-the-art sensors the size of a coffee cup have been collecting data along the way and beaming it back to the researchers, like Russell in Tucson. Within hours, the data is freely available online.

They measure ocean acidity, or pH, and other metrics to understand the biogeochemistry of the elusive ocean, but not without controversy.

Making a splash

Alison Gray, an oceanographer at the University of Washington, is the lead author on the study. She said there are two reasons the study may contradict what has previously been thought of about the Southern Ocean: The lack of wintertime observations at the ocean by other researchers and the fact that ocean carbon levels might vary throughout the year.

So while SOCCOM is making it possible to get more data than ever before, others question her nontraditional methods. They suggest that Gray’s alarming results are derived from error.

“Whether the Southern Ocean is absorbing a large quantity of CO2 from the atmosphere is a hot topic for environmental science and global policymaking,” said Taro Takahashi, a geochemist from Columbia University, in an email. He is not involved with SOCCOM.

Takahashi is not entirely convinced the measurements reported by the authors are scientifically reliable enough to support their conclusions.

The issue with the findings is that researchers are not directly measuring CO2 but rather calculating it from the measurements taken with the new sensors, he said. The standard shipboard sensors don’t work at the depth the floats operate, and the traditional sensors are too large to fit on a float.

Pushback

Publishing the paper has been laborious as well, Russell said.

SOCCOM is like the disruptive startup in the carbon counting industry.

“(Reviewers) kept saying, ‘It’s a new sensor, so if you want us to trust it, we want more time and more of them,’ which is legitimate and annoying,” she said.

Additionally, while the floats are convenient year-round tools, some worry the floats will render measurements made by shipboard crews with the older, larger sensors obsolete. But Russell wants to reassure them: “We don’t think we should ever replace the ships because that together actually gets us this transformational science.”

What’s next

Gray remains confident in her findings, “but we need to keep making measurements to verify our results,” she said.

“Even assuming large uncertainty, our results are still significantly different than previous estimates,” Gray said. “So even if we are off, the take-home message is the same.”

The team only wants to improve the models with more data so that future climate predictions can bet more accurate, Gray said.

“If the Southern Ocean is not taking up as much carbon as we believed, it could be that things are changing more rapidly,” Wanninkhof said.

And that matters, even in a desert thousands of miles from the Antarctica since climate change will make extreme weather events more extreme in Arizona, he said.