Douglas Spring trailhead in Tucson’s Saguaro National Park East is well known to the masses who hike or jog the popular system, but few likely have any idea about the heavy maintenance and restoration work that keep the trails in place — or the giant rocks hidden under many of the slopes they tread.

But on a recent spring morning, that work was underway near Bridal Wreath Falls, about 3 miles up the Douglas Spring Trail.

Here, a dozen members of the Saguaro Trail Crew had set up their workplace for the next few days. Along a stretch of trail just above a wash, they were building what looked like large stone “steps” up the trail ascent.

The “steps” you see on Douglas Spring Trail are actually small “check dams,” explained Zak Beyersdoerfer, assistant volunteer coordinator and trail crew member.

“Hikers complain about them because they are hard on the knees, and horses try to avoid them making side trails which defeat their purpose — but we put them in to create a level area that slows down water velocity to retain soil,” he said. “The goal in building trails is to conserve soil and reduce erosion.”

For a mild grade, like the Bridal Wreath Falls section, each check dam had an almost level soil bed up to a “dam” rock with a short drop to the next dam bed. A completed section looked like mellow steps with a large flat soil bed in between. Because of grade, a steep area like the first climb up from Douglas Spring Trailhead, may require shorter beds and higher “dams,” appearing much more like a steep staircase to the unhappy hiker.

“We try for a maximum of 8 inches with each step rise to try to balance soil retention with hiker comfort.” But some rocks on the trails exceed that height, he noted.

The magic of the check dams is hidden beneath the surface. Crews transport, dig holes for, bury and perfectly set large rocks to create the dam that holds the bed in place.

But the real magic of the check dams is hidden beneath their surface. The crew transports, digs holes for, buries and perfectly sets large rocks to create the dam that holds the bed in place. Therefore, the visible “step” is generally a much larger rock buried deep beneath the surface. In addition, small rocks are carefully placed and tapped into tight alignment on either side of the large rocks to get perfect dam height to minimize soil erosion.

A completed set of about nine to 10 check dams showed only the large flat “steps” and not all the intricate rock work beneath.

For the most part, an individual crew member could create a “check dam” using hand tools.

Crew members could be seen moving a large rock over half their size by using a steel bar for leverage. The big rocks are collected and rolled down from the wash. Using pick and shovel, a builder digs holes for rocks placed as foundation of check dam — both the flat rock buried under the bed and rock dam that will hold back water. When rock is moved into a pit just right, the builder chisels it to fit, then places small rocks on the side called “gargoyles” to closely fit rock into place. The builder uses a soft hammer with sand to bang rocks into place without cracking them.

And yes, sometimes after working for hours getting a big rock placed, a tap from the hammer and it splits. Trail work teaches patience, Beyersdoerfer said. It might be a half or entire day just shaping and chiseling rocks into place for one check dam.

“If you get frustrated with the work, it’s you, there is nothing but patience here,” Beyersdoerfer said. “The Sonoran desert has taught me. It has such resiliency. It keeps things in check and then springs forth when it’s time.”

Besides the daily hiking (6 miles round trip for this particular project) and physical work, “you get to put your own artistic touches on the rock work,” he said.

Life on the trail

Observing several crew members at work, care, patience and artistry were evident.

Saguaro trail members come from all over the country. This group included folks in their 20s and 30s from Michigan, Delaware, Maine, West Virginia and California. Beyersdoerfer is from Georgia.

He started his trails career working for American Conservation Experience (ACE) — a national group based in Flagstaff (with other regional offices) that recruits and trains trail crews for projects all over the country. This turned out to be a common start for several of the trail crew.

Beyersdoerfer has worked in Great Smoky Mountains National Park in North Carolina; parks in New Jersey and Georgia; and in Arizona and Grand Canyon National Park, the Havasupai Indian Reservation and Tonto National Forest (Pinal Mountains near Globe.)

After a couple of years’ change from trail scene as a gardener (which evoked an interest in natural history and biome ecology), Beyersdoerfer took a job with Saguaro in 2001. “The West had left a lasting impression.” With an academic background in film and sociology, he liked the mix of outreach, trail work and conservation education. In the summer, he works with the park’s Youth Conservation Corps (a federal program that gives youth summer jobs in national parks, forests and wildlife refuges).

The trail crews are seasonal. Saguaro National Park hires 24-25 people (four crews of six members) during its winter season November-May; along with six to 12 trail crew members in the summer. Saguaro is ideal for many seasonals, who also work temporary jobs in colder climate areas like Rocky Mountain or Yosemite national parks.

A trail runner heads back to the trailhead as sun sets over the Douglas Spring Trail.

“When the snow flies, it’s time to move south; when the snow melts it’s time to work in the mountains,” explained Louis D ‘Andrea, a West Virginia native on his second tour at Saguaro. “Coming down here for the winter is nice.” He has worked in Adirondack State Park in New York, at Yosemite, and all over Arizona. His summer job is on the Monongahela National Forest in his home state. How long will he be a trails professional? “As long as my body holds up.”

Rory McLaughlin from Delaware started his trails career with ACE in California, cutting out fallen logs on the John Muir Trail in the Sierra Nevada mountains. It’s his ninth or 10th season alternating months in the southwest and in the mountains. “For a while there, I was hitting a sweet spot with eight months on and four months off.”

While the two crews were working on Bridal Wreath, two more were rebuilding eroded sections on the Quilter Trail, a section of the Arizona Trail on the south side of Rincons linking Manning Camp and Hope Camp trails.

At the start of the season, in November, all trail crews were working on West Turkey Creek Trail between Miller Canyon and Deer Head Spring on the east side of the Rincons with two base camps: one a the bottom end of a trail in lower Turkey Creek near Miller Canyon and one at Spud Rock Spring, an official Park Service campsite near the top of Mica.

The Spud Rock camp was luxury: a large canvas cook tent, wood burning stove, solar power lights and other equipment packed in by Saguaro’s packer and mules. “We had a Thanksgiving feast,” Beyersdoerfer added. No camp cook: each crew member took turns preparing a favorite meal for all. An unexpected snowstorm in early December shut down that operation.

For December and January, the crews rotated through Organ Pipe National Monument near Ajo, working on trails and sealing old mines with native rocks and soil.

Not all parks have trail crews, so Saguaro often loans out its crews to Organ Pipe, Tucumcari, Coronado and Chiricahua monuments, all nearby desert areas.

This month, crews are working on a nearly level trail west of Douglas Spring trailhead, installing logs and moving tools between work sites. Some members are already leaving for their summer jobs; a few will stay through May for wind-down work including logistics, gear inventory, sharpening tools and sanding down handles and hammers.

The summer trail crew “tries to stay ahead of the heat,” often working from Manning Camp at 7,920 feet on a flank of Mica Mountain, working on the large trail system that loops Mica.

Photos: Saguaro National Park through the years

Saguaro National Park

Updated

The Saguaro National Monument cactus garden in 1955.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

The Saguaro National Monument visitors center in 1955.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

The Saguaro National Monument visitors center in 1955.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

The Saguaro National Monument visitors center in 1955.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

The Saguaro National Monument West visitors center, left, with two rangers' apartments under construction in 1966.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Saguaro National Monument East unit loop drive in 1958.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Saguaro National Monument East, ca 1950s.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Saguaro National Monument in 1935.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Snow at Saguaro National Park East (then called Saguaro National Monument) on Dec. 23, 1965.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Undated photo (probably 1950s) of tourists enjoying picnics and hiking at Saguaro National Monument.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Saguaro National Monument visitors center ca 1940s.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

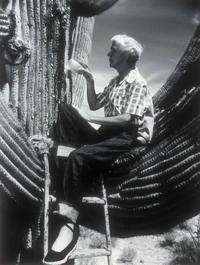

Home Shantz, a plant scientist and president of the University of Arizona in the 1920s, was instrumental in establishing Saguaro National Monument in 1933.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Panorama of cactus forest in Saguaro National Monument, 1931.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Dr. Alice Boyle applies Penicillin to a Saguaro cactus at Saguaro National Monument. Dr. Boyle’s studies of saguaros included treatments with penicillin that were somewhat successful. Later research showed that the loss of old saguaros was a result of age and periodic freezes, not a “blight”!

Saguaro National Park

Updated

The Freeman family in Saguaro National Monument in 1936.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Freeman's adobe home in Saguaro National Monument in 1934.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A park ranger with visitors on the loop drive in Saguaro National Monument in 1961.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Centennial Saguaro cactus outside the Saguaro National Monument visitors center.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Saguaro National Monument cactus

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Snow storm in Saguaro National Monument in 1937.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A view looking south from Signal hill at the Tucson Mountain Range in Saguaro National Park, Tucson Mountain District in 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A view looking east from Saguaro National Park, along Picture Rocks Road in the Tucson Mountain District in August, 2016. In the distance, cloud rise over the Santa Catalina Mountains.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A Saguaro carcass framed at the Saguaro National Park, West, The Tucson Mountain District (TMD) in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A southerly view out the window of a picnic shelter built by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930s that was built with surrounding rock in the Ez-Kim-In-Zin Picnic Area at the Saguaro National Park, West, The Tucson Mountain District (TMD) in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A desert tortoise makes its way down Kinney Rd. in the Saguaro National Park West, Wednesday, August 10, 2016, Tucson, Ariz. Kelly Presnell / Arizona Daily Star

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A Saguaro cactus off Golden Gate Rd. holds a top full of flower buds at the Saguaro National Park, West, The Tucson Mountain District (TMD) in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A view looking south from Signal hill towards Wasson and Amole Peaks from left in Saguaro National Park, Tucson Mountain District in August, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Visitors take a look at trail maps on the patio of the Red Hill Visitor Center at the Saguaro National Park, West, The Tucson Mountain District (TMD) in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Visitors from Denver stroll one of the many trails off Golden Gate Rd. at the Saguaro National Park, West, The Tucson Mountain District (TMD) in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Panoramic view from Spud Rock, including the city of Tucson, from six images, ranging from southeast at left to northeast at right, near Mica Mountain on the western slopes of the Rincon Mountains in the Saguaro National Park on June 2, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A hawk watches from his perch at the Saguaro National Park, West, The Tucson Mountain District (TMD) in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A zebra-tailed lizard (Callisaurus draconoides) perches on a rock near the Signal Hill Picnic Area at the Saguaro National Park, West, The Tucson Mountain District (TMD) in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Panther and Safford Peaks in the Tucson Mountains North of Saguaro National Park, West, The Tucson Mountain District (TMD) in 2015.

Ha:san Bak, Saguaro cactus fruit harvest

Stella Tucker uses the sharp edge of a stem of a Saguaro fruit to slice the husk to get to the sweet meat inside as she harvests the fruit in the Saguaro National Park in 2005.

Ha:san Bak, Saguaro cactus fruit harvest

Stella Tucker uses a kuipaD to harvest saguaro fruit in the Saguaro National Park 2005. During the early summer Tucker camps out in the park to harvest and cook the fruit just as her Tohono O'odham ancestors did. Tucker died in 2019 at age 71.

Ha:san Bak, Saguaro cactus fruit harvest

Bob Martens uses a kuipaD, lengths of Saguaro ribs topped by a small limb of creosote, to knock down ripe Saguaro cactus fruit as he helps Stella Tucker during the Tohono O'Odham harvest at Saguaro National Park in 2005.

Ha:san Bak, Saguaro cactus fruit harvest

Under the early morning sun, Jerry Yellowhair strengthens the joint where a small creosote branch is attached to a length of Saguaro rib to make a kuipaD, used to reach the Saguaro fruit.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

1907: Prominent Tucsonan Levi Manning and his family spent the summer at a get-away log cabin high in the Rincon Mountains.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Manning Camp in the Saguaro National Park East, in 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Some of the pots, pans and iron skillets used by the staff during their stays at Manning Camp in the Saguaro National Park on June 2, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Next generation ranger Ryan Summers, left, and wilderness ranger Shannon McCloskey look over the camps visitors log shortly after arriving at Manning Camp 8,000 feet above sea level in the Saguaro National Park, on June 2, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Horse shoes on one of the logs making a wall in the cabin at Manning Camp in the Saguaro National Park on June 2, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Next generation ranger Ryan Summers splits wood for the evening's fire at Manning Camp in the Saguaro National Park on June 2, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

The view east over Reef Rock, lower left, from Rincon Mountains near Manning Camp in Saguaro National Park, June 2, 2016

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Wilderness ranger Shannon McCloskey, left, and next generation ranger Ryan Summers prepare to do some upgrades to the facilites at Manning Camp in the Saguaro National Park on June 2, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Sid Kahla, left, and Thor Peterson get a pannier balanced on Goose while packing seven mules for a resupply of Manning Camp ranger station in 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Saguaro National Park trails supervisor Nick Huck, left, and chief of maintenance Jeremy Curtis split up a box of paper towels, distributing the weight evenly among the panniers while preparing for a pack mule resupply of Manning Camp on April 14, 2016. Seven mules were in the supply train and each mule can carry between 100 and 120 pounds.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Wasson and Amole Peaks at the Saguaro National Park, West, The Tucson Mountain District (TMD) in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Monsoon clouds gather over the cactus forest in the Saguaro National Park West, Wednesday, August 10, 2016, Tucson, Ariz. Kelly Presnell / Arizona Daily Star

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Saguaro cacti backlit by western sun at the Saguaro National Park, West, The Tucson Mountain District (TMD) in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A horizontal sliver of sun catches a stretch of cactus in front of the Rincon Mountains just off the Mica View Trail in Saguaro National Park East, Friday, August 12, 2016, Tucson, Ariz. Kelly Presnell / Arizona Daily Star

Saguaro National Park

Updated

This old stone building was constructed in the 1930's by the Civilian Conservation Corps at the Cam-Boh Picnic Area at Saguaro National Park West.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

In the aftermath of an evening summer storm, lightning arcs through the night skies over the Saguaro National Park West in 2012.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Saguaro National Park trails supervisor Nick Huck, left, and chief of maintenance Jeremy Curtis split up a box of paper towels, distributing the weight evenly among the panniers while preparing for a pack mule resupply of Manning Camp on April 14, 2016. Seven mules were in the supply train and each mule can carry between 100 and 120 pounds.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A Harris' antelope squirrel, a year-round resident of the Sonoran Desert, comes out of from under a bush for a look-see near the Golden Gate Road at the Tucson Mountain District of the Saguaro National Park in 2010.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A jack rabbit munches on some greens near the Broadway Trial Head at Saguaro National Park Rincon Mountain District in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Hikers in Saguaro National Park, like these on the King Canyon Trail in the park's unit west of Tucson, can pay park entrance fees at trailheads using a smartphone.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Loop of connected trails at Saguaro National Park East, made up Shantz, Pink Hill, Loma Verde, Cholla and Cactus Forest trails in 2012.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

From atop an outcropping under the Rincon Mountains, Next Generation Ranger Ryan Summers points out the ancient fault line that shifted and formed the Tucson valley to a group of visitors during a geology tour of Saguaro National Park East on April 26, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Saguaros stand on a ridge line as massive storm clouds drift in the distance along the Hohokam Road at the Tucson Mountain District of the Saguaro National Park in 2010.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Chief of maintenance Jeremy Curtis gets the strap as tight as possible with the help of trail supervisor Nick Huck while preparing a 70+pound propane tank for a pack mule resupply of Manning Camp in the Saguaro National Park, Rincon District on April 14, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Saguaro National Park ─ Sunset can be a colorful time along a network of trails near the eastern end of Broadway.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Ranger Donna Gill points out cactus flowers and birds during the Twilight Glow to Moon Shadows hike on the Sendero Esperanza Trail at Saguaro National Park West in April, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Hedgehog cacti are in brilliant fuchsia bloom at many sites around Tucson from Sabino Canyon to Tucson Mountain Park and Saguaro National Park in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Russell Jones takes a picture at the Saguaro National Park West Red Hills Visitor Center in 2009.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Poppies were blooming profusely at Saguaro National Park West on February 23, 2015

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Mike Ward of Saguaro National Park, left, and volunteer LaDeana Jeane observe a Saguaro cactus while conducting a census at the east section of Saguaro National Park in 2009.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Gavin Youngstrum drives a roller along the bed of the new Mica Springs Trail, work which will make it ADA compliant in Saguaro National Park East on April 22, 2016, Tucson, Ariz. Power tools and motorized equipment is used very rarely in the park. The trail is not in a wilderness area so the prohibition on the use of power tools and machinery doesn't apply.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A blue Arizona lupine mixed in with a handful of yellow bladderpod along the Ringtail Trail in Saguaro National Park Tucson Mountain District in 2013.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Park Ranger Ann Gonzalez watches the campers in her group as they go over a map during Junior Ranger Wilderness Day Camp at the Saguaro National Park in 2009.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Petroglyphs are among the many wonders at Saguaro National Park West.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Runners top the first climb as the sun rises at 6:30am, during the annual 8K Saguaro National Park Labor Day Run at Saguaro National Park East in 2007.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A saguaro under the stars, including a smudge of the Milky Way, at the Broadway Trail Head at Saguaro National Park Rincon Mountain District in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Sunset reflected in a mud puddle left over from heavy rains a few days earlier at the Broadway Trail Head of the Saguaro National Park Rincon Mountain District in 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

The moon hangs high over Wasson Peak as Ranger Donna Gill leads hikers during the Twilight Glow to Moon Shadows hike on the Sendero Esperanza Trail at Saguaro National Park West in April, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Volunteers help yank out the nonnative, invasive buffelgrass at Saguaro National Park East.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Using a laser, amateur astronomer Joe Statkevicus points out a few interesting objects in the night sky to Landon George and Vickie Miller at a Saguaro National Park East Star Party in 2010.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A bee works through a patch of baldderpod in the Saguaro National Park Tucson Mountain District along the Ringtail Trail in 2013.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Trail worker Brad Duffe redistributes material as he and his trail crew lay down a bed for a new surface, part of remodeling the Mica Springs Trail to make it ADA compliant in Saguaro National Park East on April 22, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Riders maneuver their mounts down a hillside just north of the Douglas Spring Trail in the Saguaro National Park Rincon Mountain District, Friday Nov. 27, 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Tim and Connie Phillips, from Salt Lake City, look for photo angles during the Twilight Glow to Moon Shadows hike on the Sendero Esperanza Trail at Saguaro National Park West in April, 2016. The retired couple sold their home and are "following the weather" across the country in their RV.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A few items, photos and brief entries in tiny notebooks from an unofficial shrine at Mica Mountain in Saguaro National Park on June 2, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

The sun sets over the Saguaro National Park Rincon Mountain District on Oct. 8, 2015.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Scarlett Gates and the rest of the tour group watch the last few minutes of daylight from a rock outcropping along the Tanque Verde Ridge Trail during their guided sunset hike in Saguaro National Park East on April 16, 2016.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Gold poppies stand out against a backdrop of cacti and blue desert sky at Saguaro National Park west of Tucson on March 11, 2019.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

Rainbows pop up over Saguaro National Park East, as the first major monsoon storm of the season begins to roll into the valley, Tucson, Ariz., July 11, 2020.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A half rainbow arcs over Saguaro National Park East as a highly localized cell of monsoon rain sweeps through a small band of the eastern valley, Tucson, Ariz., July 28, 2020.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A light coating of snow remains on the Rincon Mountains seen nearby the Broadway Trailhead in Saguaro National Park in Tucson, Ariz. on January 27, 2021.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A cactus in the Saguaro National Park East stands in front f the snow in the higher reaches of the Santa Catalinas, Tucson, Ariz., March 13, 2021.

Saguaro National Park

Updated

A lighting strikes hits in the Saguaro National Park, east of Tucson, Ariz., July 29, 2021, one of several storm cells that skirted the city.