He was just a boy when his dad was killed, leaving Bill Kelley much to learn about the man his dad was through the many letters and writings he left behind and from the people who knew and served with him.

“He was such a great writer,” Kelley said. “It was fascinating to read his letters, especially to his father.”

Victor Bruce Kelley was killed in Vietnam on April 28, 1965. He was the second Tucsonan killed in the war that lasted for more than a decade and claimed the lives of more than 58,000 Americans.

Bill Kelley, 59, was 10 years old when his father was killed, and has many memories of him. For example, he can recall his father terrifying him and his siblings by pretending to drive with his hands over his eyes while navigating mountain passes on a family trip in Germany where Bruce Kelley, as he was known, was stationed in the Army.

It wasn’t until adulthood, however, that Bill Kelley came to appreciate his father as a man of intellect, keen observation and curiosity.

The letters and notes the elder Kelley left behind helped his son to better understand the man he knew simply as his dad — a man who would serve his country in three wars, ultimately giving his life in an effort to save a comrade.

“In my reflections as I grew older, and certainly as I became a father myself, I would reflect on all of those things through his writings,” Kelley said.

Bruce Kelley’s intellect, analytical mind and inquisitiveness are evident throughout the writings, particularly in an early outline of a book he intended to write about his Vietnam experiences.

What we have often encountered in the field of advice is the reluctance of the Vietnamese to accept the recommendations offered. The reasons are as varied as the individual personalities involved. The most serious general observation has been a lack of aggressiveness in combat; the absence of battlefield desire to close with and destroy an enemy. This has continually hampered the ARVN’s (Army of the Republic of Vietnam) military effort.

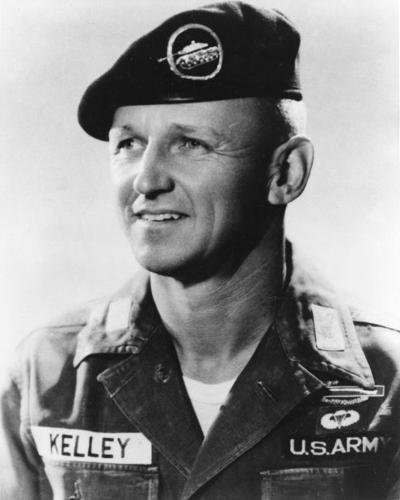

Victor Bruce Kelley, 1965

Bruce Kelley was born on June 19, 1928.

His parents, Victor H. Kelley, a well-known professor at the University of Arizona, and Mary Kelley moved to Arizona from Kansas as the Great Depression ravaged rural America. The family originally settled in Flagstaff, where Victor H. Kelley was a Naval reservist and a professor at what was then called Arizona State Teachers College of Flagstaff, later to become Northern Arizona University.

The call to serve grabbed Bruce Kelley early on. He graduated from high school at 16 and was allowed to enlist in the U.S. Navy at 17, just as World War II was coming to a close. As a skinny teenager, he served in the Pacific theater for the final months of the war in 1945.

After a few years of service, the elder Kelley returned home to Tucson — where his father was a professor — and enrolled at the University of Arizona to study political science. While there, he earned his commission as a second lieutenant through the Army ROTC program.

He also met Patricia Hedgcock, whom he later clandestinely married in Florence in 1950. The newlyweds later held a proper marriage ceremony at Kelley’s new in-laws’ ranch near Sonoita.

The Kelley's had four children all together: Susan, Howard, David and Bill.

By 1952, he again felt a strong desire to serve. The country was at war in Korea, and though he had a growing family by then, Kelley was ready. In Korea, he earned the Bronze Star and a Combat Infantryman Badge.

After the war, he decided to try his hand at civilian life once more. He returned to Tucson and again enrolled at UA, this time to earn a master’s degree in education.

In 1955, Kelley packed up his young family and set out for Oxnard, California, where he taught high school and coached sports.

While there, Bill Kelley and his brother, David Kelley, were born.

But it wasn’t long before the call to service once again gripped him.

“He didn’t like teaching; he loved the military,” Bill Kelley said.

Kelley re-enlisted in the Army in 1958, where he once again earned distinction, eventually completing Airborne and Ranger training.

During these years, the Kelley family moved numerous times. As the young officer’s assignments changed, the family shifted from California to Texas, Kentucky, Georgia, and eventually Germany.

In Germany, Kelley was a staff officer in the same 3rd Armored Division in which one of America’s biggest icons, Elvis Presley, was serving.

In the fall of 1964, having earned the rank of captain, the Army decided to send Kelley to the then-little-known country of Vietnam, where thousands of American military advisers were training and counselingthe country’s leaders in an escalating internecine war against North Vietnam. It was during his service there that Kelley’s writings most clearly showed his analytical mind.

An ambivalence about the growing U.S. involvement in Vietnam was clearly at odds with his sense of duty. He questioned some of the policies at play in his writings to friends and in a commentary where he handwrote his thoughts next to passages clipped from an article titled “A Life Panel: The Lowdown From the Top U.S. Command in Saigon,” from a November 1964 issue of LIFE magazine.

I feel in my own heart that to abandon this cause would be a national tragedy — if not immediately, at least will in our lifetime. At the same time, I also feel to further commit our forces would be just as tragic. … I guess I can’t write the nice catch phrases home as to why I’m here like “safe for democracy,” “last outpost against communism,” “so the children won’t have to do it,” etc. I’m here because the Army sent me, I’m here to help another professional soldier (and the ARVN officer for better or worse is just that) do a job by providing him with my professional counsel.

Victor Bruce Kelley, 1965

“He would have been a general, no doubt in my mind,” Bob Ainsworth said. “Bruce was the greatest leader I ever knew.”

Ainsworth, 79, met Kelley in 1958, when they were stationed together at then-Camp Irwin in the deserts of San Bernardino County, California.

“He was kind of like my big brother, he looked out for me,” Ainsworth said from his home in Upland, California.

The two would go on to infantry and Airborne training, and served together several more times. Both later served in Germany and Vietnam at the same time, though at different posts.

Ainsworth, who spent 20 years in the Army, eventually retiring as a lieutenant colonel, remembers Kelley as someone with whom he used to pull practical jokes.

“I think we encouraged each other and challenged each other; that’s how we got in trouble,” he said.

He recalled when both men grew frustrated at the training in Airborne school that seemed geared toward absolute beginners. Basic things, Ainsworth said, like instructing soldiers on the proper end of a rifle to hold.

So the two set out to poke fun at the training manuals by writing a one-page sendup.

“It became a sensation,” Ainsworth said. So much so, however, that it caught the attention of the general in charge, who called the two satirists into his office for a stern dressing down.

For Ainsworth, this was the Bruce Kelley he remembers — a soldier at heart, a true intellectual and someone who found enjoyment in all aspects of life.

“He had a rough exterior, but underneath he was a big pussycat,” he said.

The Vietnamese boil everything they eat — rice being the basic food. ...I have found the food to be tasty but you’ll never get fat on it; I have no problems eating it (remembering my favorite soup as menudo should give you an insight to my oddball tastes) although many Americans can’t make it.

Victor Bruce Kelley, 1965

After completing his duties by mid-1965, Kelley was to be reassigned — but like so many servicemen before him, his young life was cut short amid a barrage of gunfire.

“It was sad; he was going to go to Leavenworth,” Bill Kelley said.

Ainsworth, who was serving farther north in Vietnam when he heard the news of his friend’s death, traveled south to Vinh Long to learn the circumstances. He found out Kelley had been reassigned, and his replacement already installed. But someone called in sick that day, and his friend volunteered to fill in.

Kelley and his co-workers learned that a unit of the South Vietnamese army — or the Army of the Republic of Vietnam — and an American adviser had been ambushed nearby. The American adviser had been injured, and his comrades were unable to reach him through sniper fire.

“Bruce, being the kind of guy he was, grabbed about four or five ARVN guys,” Ainsworth said.

The men headed out to rescue their comrades. Kelley left his armored vehicle in search of the wounded American. Locating the man, Kelley hoisted him over his shoulder, intending to carry him to safety.

That’s when a sniper’s bullet stuck Kelley in the head, killing him instantly.

He was 36 years old.

The VC are good. They’re not supreme, but they understand guerrilla warfare and they damn well employ tactics to fit their abilities. I’m eternally grateful that they do not have more imagination than they do, as they could — with little effort — quickly convert this war into a national disaster.

Victor Bruce Kelley, 1965

Ainsworth accompanied his comrade’s body to Tucson to attend his funeral. Victor Bruce Kelley was buried on May 7, 1965, in East Lawn Palms on East Grant Road.

He was awarded the Silver Star, the Soldier’s Medal, the Bronze Star, the Air Medal and a Purple Heart.

Despite losing his father at such a young age, Bill Kelley says he’s never been bitter or resentful.

“From the time I could remember, I knew that was a possibility,” he said.

He laughs a little at the naming of the bowling alley at Fort Knox, Kentucky, in honor of his father, who served there. “Kelley Alley” has since been rebuilt into a more auspicious training facility, the Kelley Combat Marksmanship Center.

The younger Kelley and his family attended the dedication ceremony in 2004.

“He loved it,” Kelley said of his dad’s military career. “This was what he chose to do.”