While serving in Vietnam in 1969, Michael Matthews never took his Navy-issued .45-calilber pistol out of its original packaging.

Instead, he checked the pistol into his civilian luggage and used the holster to carry a knife, fork, spoon, and a pair of sunglasses.

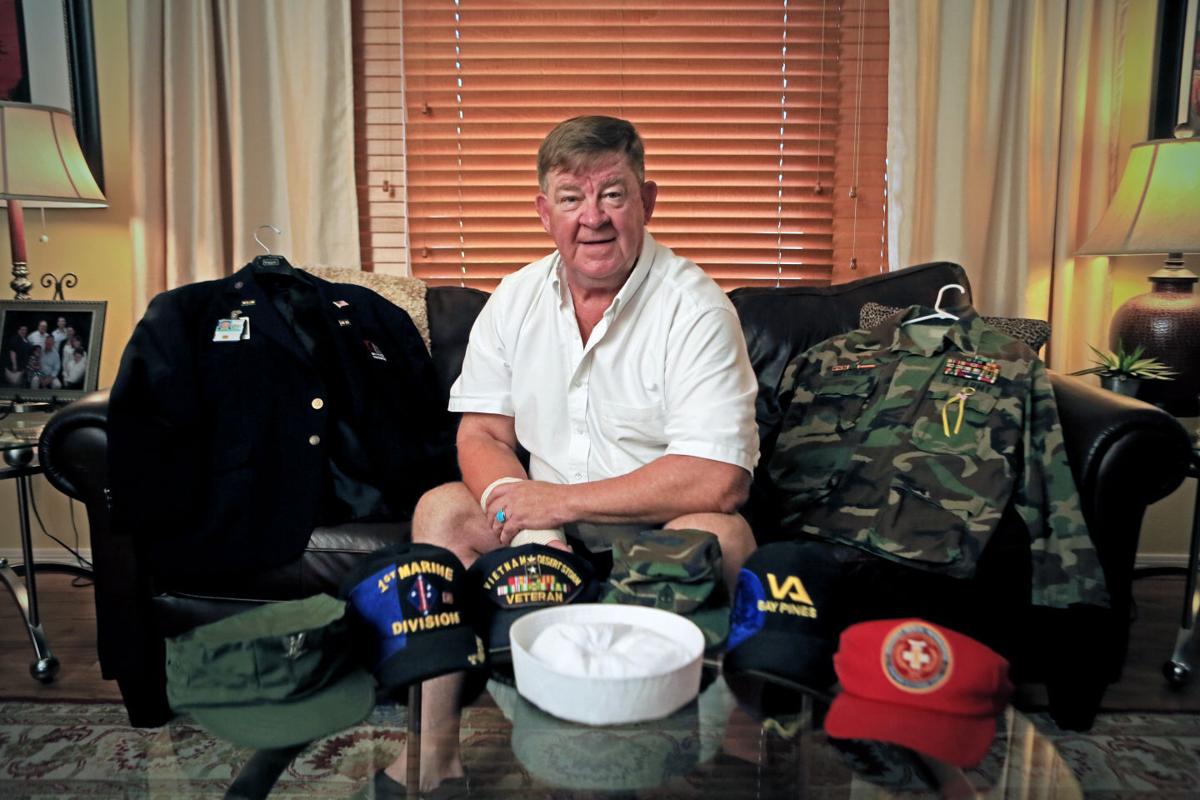

“I wanted to serve my country, but I didn’t want to kill anybody,” said Matthews, 67, a devout Catholic since his boyhood in Syracuse, New York.

His faith prohibited him from violence, so he volunteered to work as a medic.

He spent seven months in the jungle alongside Marines, all of whom were younger than 21-year-old Matthews, as they tried to cut supply lines to North Vietnamese forces.

The last six months of his tour were spent in an environment much more in line with his faith.

He worked as a scrub nurse in a hospital “like a MASH unit you’d see on TV,” he said. The hospital treated the wounded, regardless of whether they were “friend or foe.”

“Even if they were wounded prisoners, we took care of them. We didn’t ask ‘name, number, and insurance card, please,’” he said.

He and the other medical personnel came to refer to the unit as a “car wash.” Patients were stripped of their clothing, washed, covered in antibiotics, and readied for the operating room.

Working in the hospital wasn’t without its own risks. In one case, a Vietnamese farmer showed up with a small wound in his chest and the medics cleaned him up for surgery.

“We were just getting ready to cut him to fix the wound in his chest when the X-rays came in. There was a 40-millimeter unexploded mortar round in his chest,” he said.

He helped the doctor carefully remove the mortar with obstetrical forceps covered with rubber tubing. Always one for humor, Matthews joked that he needed a clean pair of underwear after the bomb disposal unit carried away the mortar round.

His aversion to carrying a gun incited some “snide remarks” at the gun range one day. Unbeknownst to his fellow soldiers, Matthews had earned an expert badge with the M-16 rifle. He accepted a $110 bet that he couldn’t hit the target once. He hit it five times.

“I knocked the head off the target, dropped the clip, gave the gun, gave the clip, said ‘thank you,’ and walked away $110 richer,” he said with a laugh.

He left active duty shortly after he returned from Vietnam but served as a scrub nurse in the New York Army National Guard and then the Army Reserve.

In 1990, he served in the Persian Gulf War at a 1,000-bed hospital in Oman designed to treat victims of biological or chemical weapons. The hospital remained empty throughout the war, making his time there rather uneventful.

“All I did was work on my volleyball serve and eat peanut butter and jelly sandwiches,” he said.

He moved to Florida after the war ended and worked as a scrub nurse at a Veterans Affairs hospital.

“I got good at my job and I actually liked going to work,” he said. “The pay wasn’t the best, but I thought I was doing some good.”

“Somebody would come in with a break or a problem and I was part of the solution to fix it and they went out the door cured or fixed or whole. That made me feel good,” he said.

He retired as a scrub nurse in 2008 and moved to Marana.

For the past six years, he has volunteered at the VA hospital in Tucson as a concierge, helping veterans make their way around the hospital. He also is a Eucharistic minister at Our Lady of the Desert Church.