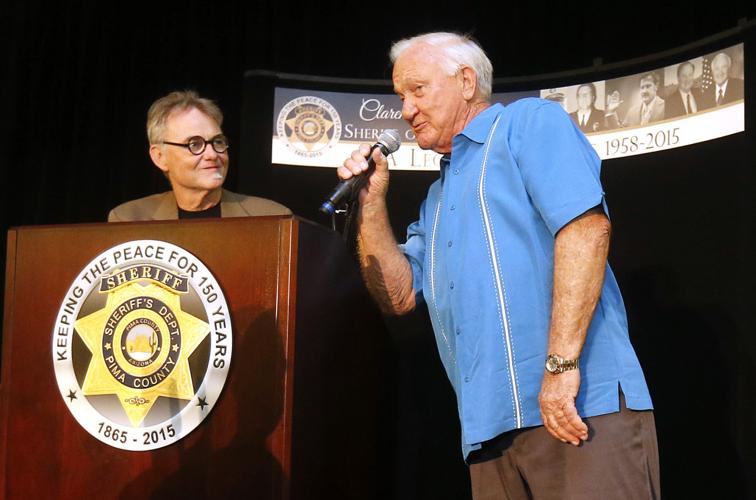

Representatives of Cenpatico, the company that will oversee the public behavioral health system in Pima County as of Oct. 1, were in the middle of introducing the network to a group of law enforcement, justice system and mental health care agency folks when the conference room door opened and in walked Sheriff Clarence Dupnik.

It was July 31, his last day on the job. He stopped in to speak to a meeting of the Mental Health Support Team, a group of representatives from law enforcement agencies, the Pima County Attorney’s Office, behavioral health agencies and others. The team meets regularly to talk about how to better address mental illness in our community.

Police officers and the court system often deal with the effects of mental illness: people who are suicidal, people who are responding to voices no one else can hear, people who are dealing with mental illness symptoms and making others worried or uncomfortable enough to call the cops.

Dupnik has long been forthright, compassionate and realistic about the need for better mental health care in our community — and what can go so horribly wrong when people who are dangerously mentally ill go untreated.

When he talks about it, Dupnik is often quick to point out that people with mental illness are far more likely to be victims of a crime than to commit one. But the specter of the Jan. 8, 2011, mass shooting murders in Tucson, done by a young man with untreated schizophrenia, is never far from the minds of many.

The connection between serious mental illness and violence is statistically small, but perceptually powerful. People living with mental illness must deal not only with their personal medical situation, but also with the wrong assumption that mental illness equals dangerous.

“The public believes that if we encounter someone with schizophrenia, we can take them to you (agencies) and you figure it all out and make them normal,” Dupnik said. “We know that’s not going to happen.”

Dupnik is likely right about the public’s expectation about “fixing” people. But mental illness doesn’t work that way. One of most frustrating aspects of many diagnoses is that the person with the illness doesn’t believe they’re ill at all.

“You guys are involved in working on one of the most difficult and frustrating issues that we have in our society,” Dupnik told the group. “Some future society will look back on us and laugh about how we deal with mental illness.”

Cry, more likely.

The Tucson Police Department answers about 60 calls each day that are connected to mental illness. Cenpatico plans to add more mobile response teams of behavioral health professionals that law enforcement can call on for assistance. This is a definite good step, but it’s clear that TPD calls alone could keep a fleet of mobile teams occupied.

Roughly 40 of those TPD calls are requests to take the caller or someone else to the Crisis Response Center, which is essentially Pima County’s emergency center for behavioral health issues. It’s located at Ajo Way and Country Club and offers urgent psychiatric care services and helps people get connected with community agencies that address mental health and addiction.

TPD makes about 500 drop-offs at the CRC each month — drop-offs, not people. Some are repeat users who go to the CRC, get stabilized, are released but don’t have follow-up care, or do but don’t comply, and end up back at the CRC.

The revolving door needs attention, the group agreed. People in a mental health crisis used to routinely be taken to the Pima County Jail, because there was nowhere else for them to go. Taking them to the CRC is a big improvement, but the work to get people help in the community, where they live, is a constant endeavor.

Dupnik acknowledged the challenge but struck a hopeful note.

“Thank you for getting together and working on a problem that really doesn’t have a solution,” he said. “But we can make things better.”