“In the heart of the Pinal Mountains in Arizona, and the center of what is known as the Apache country, is a little valley of not more than 150 acres in extent,” wrote J.C.Y. Lee in his 1873 report to the Smithsonian Institution. According to Lee, he had “never seen as rough a country, and have no words to adequately describe it.”

Lee was viewing one of the most ancient sites in Arizona — Besh-Ba-Gowah — so named by archaeologist Irene Vickrey during her excavation of the area more than 60 years later in 1935.

Luella Irene Singleton was born April 4, 1910, in Hume, Illinois. Throughout her life she suffered from lung and respiratory issues. After attending the University of Indiana for several years, taking pre-law and archaeology courses, she came west hoping the dry climate would improve her breathing problems.

In 1930, Irene arrived in Globe and found work as a legal stenographer. The following year, she married Globe schoolteacher Parke E. Vickrey who was 24 years her senior. Apparently, the couple was concerned about the differences in their ages as they both lied on their Yavapai County marriage application. Twenty-one-year-old Irene listed her age as 28 while 45-year-old Parke said he was only 38. Regardless of their deception, the marriage was founded on a shared interest in archaeology.

Parke was teaching industrial arts and serving as an athletic coach for Globe High School, but he was an avid archaeology student at the University of Arizona and had already participated in field trips conducted by famed archaeologists Byron Cummings and Emil Haury. Irene also took archaeology courses at the university and joined her husband on summer excavation excursions conducted by these two eminent archaeologists.

In 1935, the city of Globe received Works Project Administration funding to excavate ancient ruins just south of town. Haury appointed Irene to head the Globe project that she named Besh-Ba-Gowah, a loose translation of the Apache words “place of metal.” She was elected to the board of directors for the Gila County Archaeological Society.

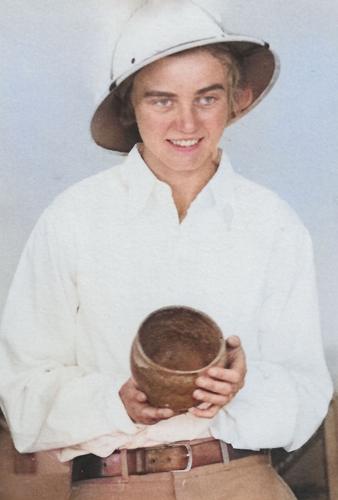

Archaeologist Irene Vickrey, who excavated Besh-Ba-Gowah in 1935.

From 1935 to 1940, 200 rooms and 350 burial sites were unearthed under Irene’s direction. Even though she was officially in charge of the operation, under federal policy during the Depression, married women could not hold government jobs as it was deemed men needed to work to support their families more than did women. Her title was relegated from foreman to “sponsor supervisor” to work around the regulation.

According to Irene, the site was probably inhabited by ancient cultures because of its abundance of water, good farming land, plenty of timber, and a profusion of game.

She estimated Besh-Ba-Gowah was first occupied around A.D. 550 by the Hohokam people and later by the Salado until around A.D. 1450. Irene and her crew discovered an abundance of pottery and shells along with stone and bone tools, baskets, jewelry and metates or grinding stones. The crew also found remains of corn and beans in large storage jars, along with hoes made from stone, signifying that the Salado farmed the area.

Deer, turkey, jackrabbit and bird skeletons, plus a variety of seeds and walnut hulls peppered the area. Animal skins were fashioned into sandals, and a form of cotton was used for clothing.

Shells were crafted into ornamental objects: beads, rings and pendants. Some were carved to represent animal figures.

The site was on a major trading route through Casa Grandes in Chihuahua, Mexico, to the Salado River near what is now the town of Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Irene estimated about 400 Salado lived at Besh-Ba-Gowah until drought and attacks from other cultures drove them out. It lay abandoned until she and her staff began their excavation.

Irene oversaw the collection and preparation of the materials found. The myriad of artifacts they amassed and recorded is one of the largest single site Southwestern archaeological collections in existence today, and one of the most complex of the known Salado communities.

In 1940, the WPA approved funding to build a museum on the site with Irene serving as curator of the museum project. The first year the museum opened, 4,000 visitors from 46 states and 11 countries stood in awe at the amount of materials amassed by Irene and her team, as well as the number of unearthed rooms.

In 1941, Irene directed a community pageant on the roof of the museum. “Last Days of Besh-Ba-Gowah” depicted life in a Salado village. The program was such a hit that it was performed annually with the proceeds going to the Gila County Archaeology Society.

Years of ancient dust and dirt clogging her lungs finally caught up with Irene, and she was forced to forgo venturing out on extended digs around the state. Yet she remained active in organizations around Globe.

Only 35 years old, Irene's lungs finally gave out on Jan. 19, 1946. She never had a chance to publish her extensive reports that she had meticulously compiled detailing her work on Besh-Ba-Gowah.

Years passed and the site was almost forgotten. In 1953, the Globe City Council approved the site as a city park. Baseball fields and parking lots were built over many of the ancient rooms and burial sites.

In 1981, the city approved restoring what was left of Besh-Ba-Gowah and in 1984, the site was placed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Today, Besh-Ba-Gowah is one of the most popular attractions in the area with the museum a great place to view activities and artifacts of long-ago cultures. Visitors are encouraged to explore the rooms, touch the walls, climb the ladders, and grind corn on ancient metates unearthed at the site.

Hours of operation and directions to Besh-Ba-Gowah can be found at www.globeaz.gov/besh-ba-gowah-archaeological-park-and-museum.

Anthropologist Rodolfo Castillo Lopez, of Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History, is placing five spools of black ribbon on the skull of Padre Eusebio Francisco Kino inside the crypt in Magdalena de Kino, Sonora.

The ribbon is now a third-relic of would-be saint Padre Kino and will be put on prayer cards to promote his canonization by Tucson’s Kino Heritage Society. The unsealing of the crypt was requested by Bishop Edward J. Weisenburger of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Tucson on behalf of the Kino Heritage Society. Video courtesy of Lupita Teran.