The Aleppo pine tree in Randy Smith’s north-side backyard was 82 feet tall and maybe 60 years old. One of many such trees in his neighborhood, its canopy spread across the yard and offered shade and sanctuary.

But nearly two months ago, the tree turned almost completely brown over two weeks. Pine cones started falling. Many, many needles were dead.

“I’ve never seen anything like it. It looked like a tree you would see falling in snow country during the winter,” Smith recalled. “One day it looks like hell, a couple of days later it looked like it’s dying and a week later it looked suffocated.”

Shortly afterward, Smith had the tree taken down, at a $2,000 cost. “It was a huge beautiful tree. It was quite a loss,” he said.

The tree is one of many big non-native pines felled all over Tucson this year. The reason: the invading pine bark beetle.

Numerous massive tree die-offs in high-elevation forests across the West in recent years have been blamed on bark beetles. That includes piñon pine deaths in Northern Arizona and other Four Corners region states in the early 2000s. But the beetle had never been seen before at this low of an elevation in the Southwest.

No one knows why beetles started killing trees here this year, how long they’ve been here or how they got here. One theory is that they came down from Mount Lemmon or other mountain ranges in firewood. Another possibility is that trees here are drawing beetles because of stress from hot and dry weather.

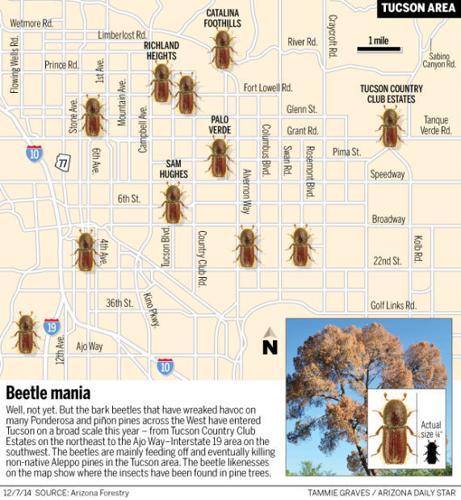

So far, at least a dozen non-native Aleppo and Eldarica pine trees have turned up with bark beetles and died here this year across eight neighborhoods, said Peter Warren, an urban horticulture agent for the Pima County Cooperative Extension Service. Like Smith’s, many of those are very large. Aleppos are common here in older neighborhoods.

Aleck MacKinnon, a certified arborist, said he removed another big dead pine about a week ago from a neighborhood east of Reid Park, behind the Doubletree Hotel. It died over three months, weighed about 8.5 tons and took up most of the yard. It was probably about 60 years old, 40 to 50 feet across, up to 60 feet high and cost at least $2,000 to take down.

The number of beetle kills is small, but that doesn’t comfort authorities. They’re concerned the beetles could spread and they say there’s probably more beetle infested trees they don’t yet know about.

Beyond that, numerous studies have linked climate change — recent, extreme heat and drought — to the rise of bark beetles and the numerous forest tree die-offs.

While it’s hard, if not impossible, to link a specific die-off to climate change, it’s likely that more will occur as the weather gets hotter and drier, said David Breshears, a University of Arizona ecologist and natural resources professor.

“We know two things with great confidence: temperatures are generally warming, and droughts with warmer temperatures are really hard on trees and can trigger or accelerate their mortality,” Breshears said in an email.

Death from top down

The beetles first came to authorities’ attention in March when several dead pines were removed from the Tucson Country Club Estates area on the far northeast side.

“A local arborist was dusting a tree that had died quickly and he brought in a sample for me to look at. He noticed it looked pretty weird,” said the extension service’s Warren.

Since then, state and county extension officials have learned of beetle-infested trees throughout the city, by word of mouth or by going door to door for them, Warren said

The most common sign of beetle infestation is a discolored crown, whose needles fade from green to a straw color to reddish orange, the extension service says.

As Warren stood next to a beetle infested, dead pine at River Road and Dodge Boulevard, he pointed to two other signs of beetles’ presence: small bits of sawdust pockmarked throughout the bark and equally small exit holes, for the quarter-inch-long beetles to leave the trees.

“Once you start looking for trees with discolored crowns, of a reddish color, you start seeing them,” Warren said. “They’re towering above homes. But we haven’t had the time or people to go out and knock on every door.”

State forest health specialist Bob Celaya said he, too, can spot beetle-infested trees just by driving around Tucson.

“This is totally unpredictable that we’d find them surviving at Tucson’s elevation,” Celaya said. “We didn’t think they’d survive. They apparently found this non-native host to feed on and reproduce.”

The beetle found here is the six-spined engraver, one of 11 species of insects living in the inner bark of pine trees that can cause rapid decline and death. It typically infests the thicker-barked and deeply fissured main tree trunks.

They’re called engraver beetles because they engrave on the wood, Warren said. The first section of dead pine tree he saw in the spring had bark that was peeling off and contained galleries, or beetle-sized tunnels, where adult males make a small house that entomologists call a nuptial chamber. From there, the male tries to attract females to come to mate.

The beetle problem appears to be worsening here, Warren added.

“In the forest, you can spray the trees with pesticides, but in neighborhoods there’s the problem with pesticide drift,” he said. “When you spray a tree with a pesticide you need to get full coverage. You wouldn’t necessarily do that in neighborhoods with a tree overarching someone’s house or several houses.”

The state’s Celaya, however, said there’s no way to say whether the beetles will become a major problem. In their native environment, they’re typically active for one year, kill whatever trees they will kill and move on, he said. Here, “I have no idea what will happen next year because of the elevation, the temperatures and because of climate,” he said.

Deep waterings needed

Typically, Aleppo pines, native to the Mediterranean region, are thought of as low-water-use plants. That’s how they’re classified in an official California publication called “Estimating Irrigation Water Needs of Landscape Plantings.”

While the Aleppo is adapted to dry weather, Warren said he suspects one reason trees are dying is that they haven’t been watered enough and get stressed, attracting the beetles.

“Aleppos in winter get desiccated by the cold, windy weather,” he said. “They need watering. After all, we’re in a drought. I wouldn’t recommend them here in the first place. They’re too big. But now that they’re here, I hate to see them go.”

He recommends that Aleppo owners water them every two or three weeks during summer, and very deeply once a month in the winter. It must be watered heavily enough to seep two feet down into a root zone that typically circles around an entire yard, he said.

Also, if you put the hose right by the tree trunk it doesn’t do much good, he said. The water really needs to be put further out, near the edge of the tree crown, where roots are absorbing water, he said.

Richland Heights residents Randy Smith and Mima Falk said they did water their Aleppos heavily — only to lose them.

Falk, a botanist, said her big tree was watered up to five to six hours at a time, once a month, during the hottest season. She stuck a probe three feet into the ground to insure it got enough water, she said.

But, “this is year 14 of a drought in the desert, and I’m not going to say we watered it every year,” added Falk, whose 40- to 50-year-old tree died last summer, three weeks after she noticed problems in it. “We started watering more in the last couple of years when we realized it was a relentless drought down here.

“For me, as a botanist, it’s always horrible to see a really big tree like that go so quickly. It’s a shame to lose any large tree in Tucson that provides shade.”

Smith said his since-departed backyard pine and two others were watered quite regularly by rainwater that poured from his roof down a downspout into an underground septic tank.

But his tree hasn’t totally vanished. Rather than pull the entire stump from the ground, he followed the advice of experts to leave three feet behind. He made the stump into a table, and uses it as a plant stand — a place to remember his prized tree.