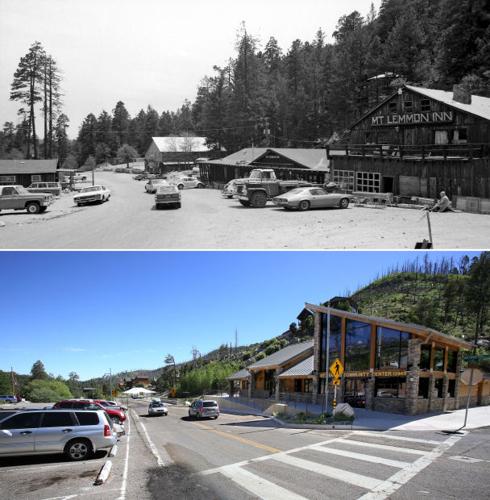

SUMMERHAVEN - Ten years after fire destroyed two-thirds of the homes in this alpine village, its devoted core of full-time residents is developing an appreciation for "a different kind of green."

Half the destroyed homes and business on Mount Lemmon have been rebuilt, but the forest in which they once sat will take centuries to grow and may never be the same.

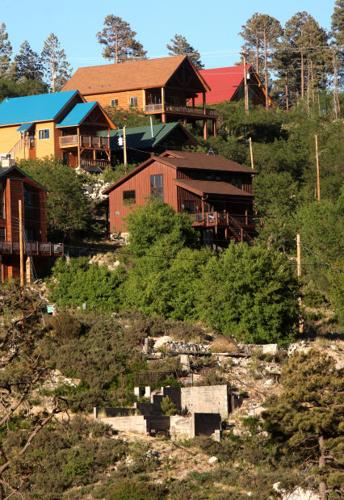

For now, at least, this is the land of big houses and small trees.

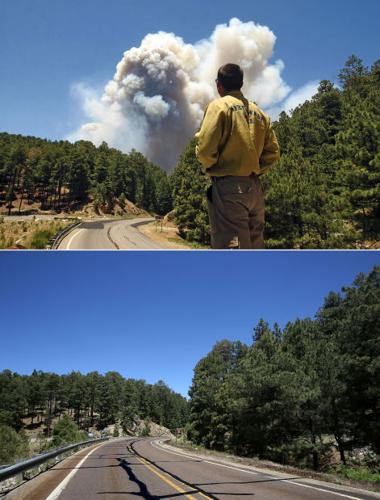

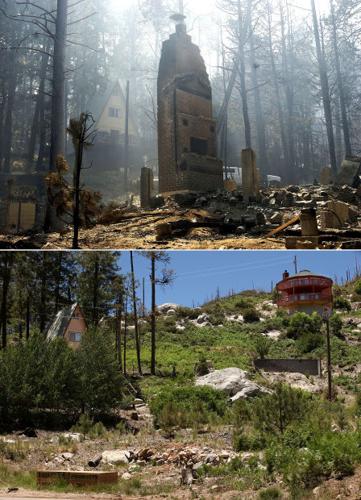

On June 19, 2003, at about 1 p.m., the Aspen Fire roared through Summerhaven, flames leaping through treetops. It destroyed 314 of the village's 467 homes, nine of its 12 businesses and a huge swath of its forest.

In a month of fire that would destroy cabins elsewhere in the Santa Catalina Mountains and threaten homes from Oracle to Ventana Canyon, the Aspen Fire burned across 84,750 acres of the Coronado National Forest.

It changed the lives of mountain residents and the look and feel of Tucson's much-loved summer refuge.

Ten years after, Summerhaven is stripped of its big pines and firs. It is sunnier and windier. Its rebuilt homes, some four times the size of their predecessors, appear even larger with that conifer curtain gone.

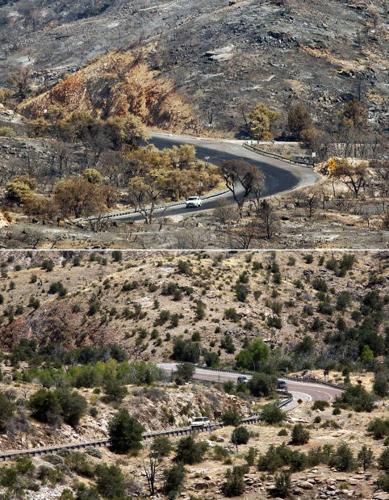

A different green

Vegetation has sprouted, but the pine seedlings planted by residents are dwarfed by faster-growing oak, aspen and locust trees. The hillsides are covered with Fendler's ceanothus, a thorny grey-green shrub that thrives after fire.

"It is a more deciduous forest," said Carol Mack, who with husband, Phil, owns the rebuilt Mount Lemmon General Store. "It is a different kind of green."

Change is taking place across the Catalinas.

On a hike up the hill from Palisades Ranger Station, Craig Wilcox points to the fields of ceanothus and sprouting scrub oak growing profusely amid the husks of blackened ponderosa pine. The same thing is occurring in Spencer Canyon and on the burned slopes of Oracle Ridge.

Wilcox, a silviculturist (forestry expert) with the Coronado National Forest, doesn't make value judgments about it and doesn't consider any change permanent. "These are all native species, and there is nothing unnatural about post-fire succession."

Whether these plants are ever succeeded by the forest that existed before depends on a number of factors, from the frequency of future fire to the continuation of our current drought to the predicted warming of the planet.

Rush to rebuild

A new built environment also rose from the ashes of the fire - a rush of construction that abruptly slowed during the recession.

Builder Dennis Cozzetti went to work on a half-finished cabin days after the fire was declared controlled. Ken Paulin broke ground for a replacement for his Fern Ridge cabin nine months after it burned. The Macks were open for business at their reconstructed Mount Lemmon General Store in Summerhaven on the first anniversary of the fire.

Debbie Fagan rebuilt her Living Rainbow Gift Shop the following spring, and Vic Zimmerman resurrected his Cookie Cabin soon after.

Pima County kicked in with infrastructure improvements. It spent $4 million in bond and community-reinvestment money to redo roads, bridges and parking lots. It built a $1.2 million community center, justifying the expense by the number of visitors who drive up the mountain, estimated at 1.5 million a year.

By the end of 2006, 111 homes, from Summerhaven to Willow Canyon, had received final inspection in the Santa Catalinas, Pima County Development Services records show.

Then the real estate bubble popped and the recession hit. In the last six years, 36 more homes were finished and 11 are in various stages of construction.

The value of land and real estate on the mountain dropped $25 million after the fire to about $67 million. It is now more than $164 million, said Pima County Assessor Bill Staples.

For some residents and business owners, said Fagan, rebuilding was "just too heartbreaking."

Alex and Char Carrillo, owners of the Aspen Trail bed-and-breakfast, walked away.

Their burned truck, now rusted, still sits in front of the foundation of the inn's entrance, dwarfed by a fast-growing aspen tree.

The view behind it is nearly as bleak as on the day they returned after the fire on July 17, 2003. They couldn't imagine attracting customers to a bed-and-breakfast overlooking a canyon of charred sticks.

The Alpine Inn, a lodge and bar/restaurant that was once the social center of the mountain, remains a bare lot.

Open and windy

The most dramatic change is the openness.

"Before the fire, you knew people lived next door to you, but you couldn't see them and couldn't hear them," said Michael Stanley, who runs the Mount Lemmon Water Co.

Now, you can hear conversations from the porch across the canyon. Stanley, who lost his rented cabin in the fire, plans to begin building his own home this year.

Residents say they feel closer to one another, their bonds formed in adversity. But there are fewer of them.

Pamela Selby-Harmon, officer in charge at the Mount Lemmon post office, said the permanent population is now less than 40. Before the fire, it was about 160.

She and her husband, Matthew, are among the emigres. Their rented cabin burned in the fire and afterwards they rented another that had survived.

"It was not the same, obviously. It was like living on the moon, and the wind was really intense."

She now commutes daily from Tucson, as does her husband, who is a homebuilder on the mountain.

Builder Cozzetti has a different view. "I'm still happy to be here. It's still beautiful, even in the burned areas. I wouldn't trade it for anywhere."

"It does definitely feel hotter," he said, and the vegetative changes support a different mix of fauna. "Raccoons used to be everywhere. Now I don't see them."

Rattlesnakes are showing up on the newly denuded rocky slopes, and he's even spotted a Gila monster.

"The turkeys are doing well and so are the mountain lions," he said. In the last couple years, at least two Summerhaven residents have discovered lion-killed deer carcasses beneath their porch decks.

The wind wreaks chaos, peeling back newly installed roofs and, in at least two cases, crashing trees through them, said Cozzetti.

"It's really windy. That's probably the most significant change."

Cozzetti, who has built or renovated 60 homes on the mountain since the fire, said the current crop is not just bigger, but better built.

Code enforcement was lax in the past. Now, the county is vigilant and a new wildland-urban interface code, enacted a year after the fire, requires construction that will withstand fire. Metal roofs, cement board and larger logs have replaced what Cozzetti calls the "tree-fort construction" of the past.

The sloped lots require cutting and filing, and the transportation of materials and workers adds to building costs, which Cozzetti estimates are $180 to $200 per square foot.

A small cabin is a bad investment under those circumstances.

The cost of building and the scarcity of building sites has kept homes large and values high on the mountain. Recent sales reach up to $300 per square foot, prices reached only in Tucson's fanciest Foothills neighborhoods. A 3,591-square-foot home on Turkey Run Road is the current record-holder, selling in 2011 for $1.18 million.

It was the first million-dollar sale on the mountain, said longtime mountain businessman and realtor Bob Zimmerman. His Mount Lemmon Realty site last week showed 16 cabins for sale, ranging in price from $285,000 to $898,000.

Third homes

Most of the homes on Mount Lemmon are vacant for much of the year.

Summerhaven was always a place for second homes, but now it holds a lot of third ones.

Many previous mountain dwellers were teachers who built modest cabins where they and their families could spend summers.

Zimmerman said his realtor father, Tony, never let teachers visit without selling them lots. Some families pooled resources and shared time.

Now, said Cozzetti, the place has been discovered by professionals, doctors especially, with busy lives and other vacation options. Selby-Harmon said her husband built one home that its owners wanted to resemble their villa in Switzerland.

One of the big new homes is seldom vacant. John Mulay, a retired physical education teacher who worked for years at Pueblo High School, said he and his wife, Linda, spend 90 percent of their time on the mountain in their new home.

Mulay has been buying, renovating and renting cabins on the mountain since 1974. He lost four of his five cabins to the Aspen Fire. He's still incredulous that the smallest of his homes, a 440-square-foot wooden A-frame on Phoenix Avenue, survived.

He was insured for about $85 a square foot but managed to negotiate replacement value at $125. He pooled the money and built a single "dream home" for about $250 per square foot.

His new home, built with humongous logs with a metal roof and wide porches, is 4,600 square feet with a full basement.

The Mulays go to Tucson only for provisions and appointments. He's on ski patrol at nearby Ski Valley in the winter. His two sons and their families spend most of the holidays on the mountain.

Things felt out of whack for a long time after the fire, Fagan said.

The hikers and recreationists disappeared, but have since rediscovered the mountain and its charms.

Fagan, who has lived in Summerhaven for 34 years, was among the early rebuilders. Her Living Rainbow Gift Shop, which reopened on the second summer after the fire, was one of the symbols of the mountain's early rebirth.

"This year feels more balanced. The mountain itself has come back. There are so many hikers now, people who really care about the mountain."

One new business, the Sawmill Run Restaurant, was developed by Bob Zimmerman and Jim Campbell on the site of the former Mount Lemmon Cafe.

New aspen, burned forest

About 20 percent of the Aspen Fire, much of it in the pine forests, was classified as a "high intensity," stand-replacing fire. That's what happened in Summerhaven, but there is still a lot of greenery evident as you leave the village to the south toward Marshall Gulch.

Where fire burned through on the ground, you must look closely to see evidence of its passing. The loop formed by the Aspen and Marshall Gulch trails takes you through the contrast. On the Aspen Trail, where the fire began, you walk through new stands of aspen and encounter vistas of burned forest.

In Marshall Gulch itself, along the flowing creek, the pines mix with maples and other deciduous survivors of the fire that burned through with little effect.

Carol Mack has taken heart-breaking walks on the Oracle Ridge and Mint Springs trails and more satisfying ones in Marshall Gulch and elsewhere on the mountain.

The Macks' decision to rebuild immediately proved to be a good one. "Business is definitely better," she said. "We were put on the map worldwide."

The lack of a real community is isolating, however. "I miss the Alpine Lodge. It was a place of community - a gathering place. Now people tend to keep to themselves."

The architecture of the new homes is eclectic, ranging from log-cabin to modern to whimsical. The locals have given some of them names - the Hobbit house and the Jetsons' pad.

They don't look like cabins in the woods but they, too, are undergoing a process of adaptation - to meet new building codes and the new reality of a forest that is no longer friendly to habitation.

Fear of fire

Even with the Aspen Fire 10 years in the past, the threat of the next fire remains.

Mount Lemmon Fire Chief Randy Ogden is terrified at this time of year to send any of his firefighters or equipment down the mountain. The Mount Lemmon Fire Department, which once made money fighting other people's fires, no longer follows that model under Ogden, who rose to interim chief in the Tucson Fire Department before resigning and taking this job.

Ogden still lives in Tucson, but at this time of year he sleeps in a travel trailer at Palisades Ranger Station.

His seven-person force relies heavily on four reserve officers and 12 active volunteers, who help patrol camping areas each day, looking for fires that haven't been properly snuffed. They've already found five this year.

There is plenty of water for fighting fires this year - one unexpected benefit of the Aspen Fire. With fewer trees sucking up water, the springs are flowing, even in late spring. And fewer customers want a share, said Michael Stanley, of the water company.

The tanks are full at fire season. There are more fire hydrants, and most homes have more defensible space between them and the next cabin or the fringe of the closest forest.

Bob Zimmerman said he likes the new openness of Summerhaven, mainly because of the lessened fire danger.

"I was getting pretty panicky before the Aspen Fire because of the density of the trees."

He is still worried and pushing for more thinning of the unburned forest in the village.

When the Aspen Fire burned through here, in the early stages of a Southwestern drought that persists to this day, it was the second- largest fire in Arizona history.

And as drought persists, bigger fires burn.

Ultimately, the fate of the forests - and the villages like Summerhaven - are linked to climate. Recent studies have noted shrinking conifer forests in the Southwest, with drought leading to beetle-killed trees and stand-replacing fires.

The future, under predicted levels of warming, is more of the same.

And already, in the 10 years since Summerhaven burned, those predictions are coming true.

The Aspen Fire is no longer the second-largest in Arizona history.

It is the sixth.

On StarNet: See more photos of the Aspen Fire and Summerhaven as it is now at azstarnet.com/gallery

Contact reporter Tom Beal at tbeal@azstarnet.com or 573-4158.