Thanks to Tucson’s unseasonably warm weather this month, the first hints of green are popping up on willow trees along the Lower Santa Cruz River in Marana. But many of those trees could dry up in the next few years — and not because of weather.

The river’s fresh water largely disappeared decades ago, mostly because of groundwater pumping, so treated wastewater has been used to nurture this stretch, which is lush with trees and wildlife as a result.

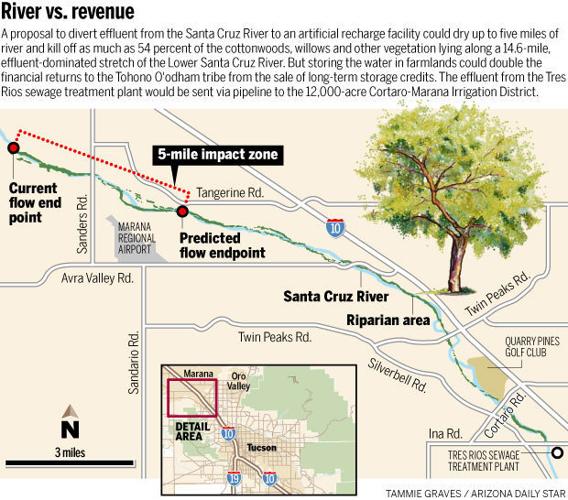

Now, though, the U.S. government is proposing to divert some of the river’s effluent supply onto neighboring farmland, to reduce groundwater pumping for the crops. The diversion would remove only about 15 percent of the effluent that runs down the Santa Cruz, but a lot more could be diverted later if the project works as planned.

The feds have another motive, too: meeting their obligation to keep Colorado River water flowing to the Tohono O’odham Nation through the Central Arizona Project. The federal fund to pay for that has run nearly dry because of the recession, higher costs, bureaucratic inattention and lack of congressional appropriations. They hope to raise money for it by diverting effluent from the Santa Cruz.

It’s not that the effluent itself will be diverted to the Tohono O’odham, however. So how would drying up part of a river raise money for the tribe?

Through the selling of water “credits.”

Builders, cities and certain other entities want to buy such credits to help prove to the state that their projects have assured water supplies as required. They can get credits toward this proof by recharging effluent into the ground to replenish the aquifer. Or, they can buy credits from others who recharge. Those credits can be used to offset their groundwater pumping.

In this case, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation wants to sell its recharge credits to make money to keep CAP water flowing to the Tohono O’odham.

Under an arcane 20-year-old quirk in state water law, the federal agency can earn twice as much legal credit — and ultimately twice as much money — if it recharges the wastewater away from the river than if the effluent stayed in the river. At the going rate for selling credits, the feds could earn about $1.12 million a year by diverting 7,000 acre-feet. A former state water director, Kathleen Ferris, says that quirk in the law wasn’t based on science but was “pulled from the air.”

So, to the dismay of environmentalists, the situation comes down to river vegetation versus competing needs and rights.

FUND FOR TRIBE

IS GOING BROKE

The Reclamation Bureau is reviewing a formal proposal to divert up to 7,000 acre-feet of the treated effluent from the Tres Rios sewage treatment plant along Ina Road northwest of Tucson before the effluent is discharged into the Santa Cruz. The effluent would go onto farm fields in the Cortaro-Marana Irrigation District.

The U.S.’s legal obligations to the Tohono O’odham stem from decades-old water rights settlement laws, to compensate for years of overpumping of groundwater beneath the tribe’s San Xavier District by the city of Tucson and others.

As it stands now, about 40 percent of the tribe’s share of CAP water doesn’t legally have a high-priority status. That means if there is a CAP shortage, that portion of the tribe’s water could be shut off much sooner than CAP water held by cities. So, the Bureau of Reclamation wants to use some money to obtain the rights to higher-priority CAP water for the tribe.

The money would also bolster a dwindling federal fund used to pay to deliver CAP water to the tribe’s San Xavier and Schuk Toak districts for farming and other purposes. It costs $4.5 million a year to deliver CAP water to the tribe. At the current rate of spending, the fund could be depleted in about four years, said Lawrence Marquez, Native American programs manager in the bureau’s Phoenix office.

“We’ve been at them for the last two years to put more money into the fund, but it’s fallen on deaf ears,” said Austin Nuñez, chairman of the tribe’s San Xavier District, who supports the bureau’s proposal. The tribe uses some of its CAP water to grow crops, including on a cooperative farm near Mission San Xavier.

“I hate to sound harsh,” Nuñez added, “but it’s come down to, do you choose being able to survive as humans with the water, or do you choose having the water in the river for wildlife and trees?”

He believes the state law should be changed to provide equity for the environment, “but that is a long haul, and we in the Indian community don’t have the resources to hire the lobbyists and the lawyers.”

LOSS OF RIPARIAN HABITAT

The Lower Santa Cruz is the closest thing Tucson has to a real river today.

The diversion proposal has drawn strong opposition from a local environmental group, the Community Water Coalition, because effluent removal could dry up as many as five miles of the Lower Santa Cruz, killing scores of native trees and shrubs. The area that would lose effluent contains 54 percent of all riparian trees and shrubs such as cottonwoods and willows living along a nearly 15-mile, effluent-dominated stretch of river, the bureau’s environmental assessment said.

In all, that stretch of river contains about 137 acres of desert riparian vegetation, considered the most productive ecosystem in North America.

The bureau’s environmental assessment on the project acknowledged that the “small, positive impact” of reducing the Cortaro district’s groundwater pumping is outweighed by loss of riparian habitat.

“The discharge of effluent into the river for the past several decades has created hundreds of acres of quality riparian habitat. Resident and migratory wildlife that utilize those areas will either be forced elsewhere or they will eventually decline or disappear,” the statement said.

At the same time, the bureau’s view is, “Our obligation under the water rights settlements is deliver water to the tribe,” Marquez said. “Effluent is one of the few resources available to us, and it’s real and it’s wet every year.”

The bureau will decide on the project later this year. For now, it’s a pilot project, to last five years and test its feasibility.

“IT’S THE DESERT”

The treated wastewater would go from the sewage plant via pipeline to the Cortaro-Marana Irrigation District, which includes 100 farmers, ranchettes and other clients. Cotton, alfalfa and small grains are grown in the district, which lies mostly in Marana.

“The key issue here is that there will still be a lot left in the river,” said David Bateman, general manager of the district. “We’re taking a small portion out. And this is not a natural riparian area — it’s the desert.”

One area that’s likely to be affected by taking out that portion of effluent is the Oxbow.

It’s a narrow, tree-lined stream that swings south from the main Santa Cruz channel, then reconnects to the river near the Sanders Road bridge in Marana. Loaded with willows, mesquite and non-native tamarisks, the mile-long Oxbow is a bird-watching hot spot and draws lots of other wildlife, said Brad DeSpain, a retired Marana utility director and former project manager of the Cortaro irrigation district. He’s now a co-owner of the Bridle Bit Ranch that’s authorized to divert some of the effluent to grow pasture for cattle.

“If we dry that river up, our wildlife here will probably be in trouble. And our business would probably be done,” DeSpain said.

Even temporary removal of the effluent will cause enormous damage to the riparian area, wrote the Community Water Coalition, representing 15 groups, in a Feb. 5 letter to the reclamation agency.

The Oxbow also contains a series of basins run by the county to recharge 600 acre-feet a year and houses migrating ducks and shorebirds. The coalition values the habitat in the Oxbow at more than $1 million.

In a letter to the bureau, County Regional Flood Control District Director Suzanne Shields faulted the proposal for failing to offer compensation for the loss of habitat and the credits the county now gets for its recharge there. Even if the effluent is eventually restored to the river, it would take decades to rebuild the riparian woodlands, she said.

“EMOTIONAL FOR

THE ELDERS”

One of the largest stakes in the water issue for the tribe lies only a few blocks east of Mission San Xavier. It’s the San Xavier Co-Op Farm, run by tribal landowners but considered an entity of the tribe, where 6,000 acre-feet of CAP water each year nourishes 860 acres.

The farm fields are mostly bright green, growing alfalfa, hay and other pasture grains sold as livestock feed. Also grown are various produce crops and traditional Indian crops such as tepary beans, corn and O’odham peas that are sold to tribal members and outsiders.

“The history of this farm starts with water. Every conversation I have about the farm starts with water,” said Cie’na Schlaefli, the farm’s food production manager. “You can’t do anything without it.”

Founded in 1971 and supplied only by pumped groundwater for many years, the farm operated on a fairly small size until large-scale delivery of CAP water to the district began in the middle 2000s and the district set up an irrigation system in 2007.

Today, the farm stretches a mile long. By next year, the farm’s operators hope to more than double its size.

If the CAP water were ever cut off, you wouldn’t see green fields here any more, Schlaefli said.

“It’s emotional for a lot of the elders. When they were growing up, they saw the fields of green,” Schlaefli said. “Then they saw it dry up. Now they get to see it come back.”

In addition to other farms, the tribe puts CAP water on three riparian restoration projects, including a large one that has brought back cottonwoods of up to 30 feet tall along the Santa Cruz southeast of Mission San Xavier, said district chairman Nuñez.

Nuñez shook his head at the irony of the tribe restoring cottonwoods while standing to benefit financially from the diversion of effluent that will likely kill cottonwoods and willows in Marana.

“We’re doing what we need to do here for the benefit of the land and the benefit of our people,” he said. “The bottom line is, it’s still very much a desert environment.”