When he moved to his Tortolita Mountain foothills home in the 1980s, Glenn Phillips’ well would run over each time it rained in the winter.

“You could pump and pump all you wanted,” he remembers.

Twenty-nine years, two more wells and $60,000 later, Phillips is no longer pumping. Every 12 days, he hauls thousands of gallons of water to his home, nestled among saguaros and ironwoods. His monthly water bill has jumped from $5 when he was pumping water to $350 now that he has to buy and haul it.

His last well, 1,060 feet deep, dried up in 2011, and he’s had his house appraised for possible sale. He would sell in a second, assuming he could find a buyer, if his wife didn’t love the area so much. “Everyone within my view has to haul or have water delivered. There are weekends on the public road when all you see is pickups with water tanks,” he says.

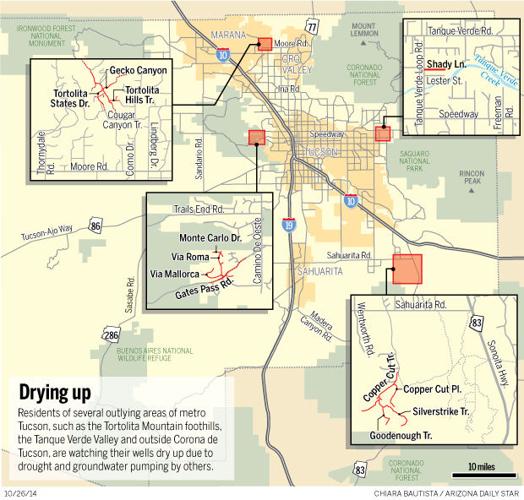

Wells are drying up all around the fringes of Tucson — the Tortolita foothills on the north, the Santa Rita Mountain foothills on the south, the Tanque Verde Valley to the east, parts of the Tucson Mountain foothills on the west.

These areas have been magnets to nature-lovers. They offer mountain views, lush desert, mesquite bosques and plenty of wildlife.

But they sit atop shallow aquifers, vulnerable to groundwater pumping and drought. While the city of Tucson’s aquifer is stable or rising in many areas due to its use of Central Arizona Project water from the Colorado River, most farther-flung unincorporated areas without CAP water have falling water tables.

The Tucson area is a long way from matching California, whose killer drought has deprived at least a dozen small communities of any water. While the CAP serving Tucson could be threatened by continued drought, that problem is five to 20 or more years away, depending on the weather and the person making the prediction.

Still, Arizona water officials say these drying wells could be the first sign of trouble for the entire region.

“It’s sort of like the canary in the coal mine,” says Frank Corkhill, the Arizona Department of Water Resources’ chief hydrologist. “People in the periphery, on the margins of a basin, where the aquifer is not highly productive to start with, are often the ones first affected by the drought.”

More homes, less water

In the Tortolita foothills, Glenn Phillips has plenty of competition for water. About 70 wells, drilled since the early 1980s, are registered with the state water department in a one-mile-wide swatch north of Cougar Canyon Trail, between Como Drive on the east and Seifert Estates Road on the west.

They range from 150 to 1,250 feet deep, with bedrock less than 400 feet.

One of the area’s first wells was dug in 1979 by Charles Hill, now 61, whose home now backs up against Phillips’. A computer scientist who designs and writes applications for computers at the University of Arizona, Hill and his wife moved here from Tucson three months after their marriage because they wanted to live under dark skies and see the stars.

His well went down 158 feet, but at times he could get water from as little as 30 feet .

“When we moved here, you could look out the door here in any direction, you couldn’t see a house,” recalls Phillips. “Now, you can see 10 houses from the front of my house and five from the back.”

The well stopped producing in 2003. Hill, Phillips and another neighbor sunk a new well at 360 feet deep. It dried up in 2005, and they drilled a third at 1,060 feet. That one, used by three families, started drying up part-time in 2009 or 2010 and completely dried up after a neighbor dug another well, Phillips recalls.

He should have seen it coming, he says, having watched the drought up there get worse all the time.

“I remember when the wash that’s down off Cougar Canyon Road below us would flow and you couldn’t get through there. At times it would flow 2 feet deep. We’d have to park down by the mailboxes and sit and wait and wait,” Phillips recalls. “It’s not doing that anymore.”

He and his wife are considering selling, although he expects to have a hard time getting a decent offer.

One neighbor who did leave is Justin Flynn, a firefighter, who with his family moved out of his manufactured home a year ago after eight years there. Living about a mile from Phillips, his family shared a well with several others. He started hauling water part-time five years ago, driving 10 miles to a Metro Water bulk water station.

“We had to restrict ourselves to 400 gallons every three days or so, and eventually it was 200 gallons every three or four days,” Flynn recalls. “It was really hard to get through the day without water. There were 10 homes around us, all having similar issues.”

He had to drive to the water station three or four times a week because his vehicle could only pull about 650 gallons at a time. And just about at that time, he says, gasoline prices skyrocketed.

Flynn and his family loved living in the Tortolitas and had planned to build there. But the lack of water drove them to move to Tucson’s west side and rent out their manufactured home, which is now for sale.

Glenn Phillips has tried to get city water delivered to the neighborhood. But his application died at the hands of the city’s new water service policies, made permanent in 2010. Those policies, created to give the city a better handle on where it serves water, put his neighborhood outside the delivery boundaries.

Marginal aquifers

Our aquifers are fed by rainfall and snowmelt, streaming downhill from surrounding mountains and recharging into the ground.

In productive aquifers, water-bearing underground deposits are hundreds of feet thick. They can be pumped for decades.

Phillips’ well and others on the fringe are probably drying up because they are drilled into marginal to poor deposits of water-bearing sands and gravels, hydrologist Corkhill says.

Typically, far-out areas are near the edge of groundwater basins, far closer to fractured bedrock than Tucson, whose aquifer runs much deeper, he says.

In bedrock, drilling for water is hit-and-miss because water exists only in rock fractures, says Wally Wilson, Tucson Water’s chief hydrologist. Bedrock can contain “great big fractures full of water” that take a long time to fill, he says.

“They can produce a hell of a lot of water for a period of time, but they drain. If there’s a drought and they’re not being replenished, it can be kind of sudden,” Wilson says.

It’s not just Tucson where this happens.

In Northern Arizona, many Navajos drive into Flagstaff for water, Corkhill says. People living near the Phoenix-area San Tan Mountains were hauling water years ago when their wells were running dry. They were doing it again a year or two ago in parts of Laveen, an unincorporated community on the southwest edge of Phoenix.

“Every now and then, when there’s been an extended period of no precipitation, we hear from people who are living on domestic wells that are really not very deep and don’t penetrate much saturated thickness in aquifer, and their wells dry up,” Corkhill says.

In Tucson right now, it’s tough to pinpoint how much this drought has reduced groundwater recharge.

“We don’t have the ability” to calculate that, says Dale Mason, a state Department of Water Resources hydrologist. “But just sitting and thinking about it, obviously if you have a drought, you have less mountain-front recharge.”

Plus, there’s competition from more wells, whose numbers have grown with Tucson’s population.

“It’s just continued overuse. Everybody comes down and wants another well,” says Jim Wise, whose Wise Pump and Tank Service installs and repairs well pumps and water tanks. “The more straws you put in the cup, the quicker the cup gets empty.”

Costly city hookups

When wells went dry a decade ago and again this summer on Shady Lane in the Tanque Verde Valley, homeowners weren’t deprived of water — just cash. They can hook up to city water.

Shady Lane is aptly named. It stretches a few blocks east of Tanque Verde Road, just north of Tanque Verde Creek, and its mesquite trees tower 40 feet or more.

The shade and greenery drew Ralph and Valerie Mathews to their home on a one-acre lot back in 2007.

“You can sit on front porches here when it’s 110 degrees and it’s still tolerable,” Ralph says. “You can see cardinals and javelina run through here, and raccoons and coyotes.”

But about 13 months ago, their toilet stopped flushing and they couldn’t get water to their washing machine. They hired a well driller and installer, Gary Hix, who doubles as a professional geologist, to “sound” their well, lowering a device into it that gives off an alarm when it reaches water. The well tested dry.

They considered digging deeper, but many companies wanted to charge them for a minimum of 200 feet of drilling whether they hit water or not, Valerie Mathews says.

First, they paid a private company to haul water to them. Then they tapped into a neighbor’s city water line, with the neighbor’s OK, and asked Tucson Water for their own hookup.

That’s where the money issue arose. The Mathews were among at least three homeowners whose wells went dry recently, nearly a decade after three neighbors whose wells went dry hooked up to city water.

At the time, the three paid $13,000 apiece to hook up, less than what it might have been because Tucson Water allowed two to install remote meters, which are hooked up not at the customer’s home but at a city water main or distribution line.

That let the homeowners avoid paying for a much larger and costlier extension from the city water line.

But Tucson Water no longer allows remote meters, which can be costly and hard to fix.

So the homeowners say they’re facing hookup costs as high as $16,000 to $20,000. Tucson Water’s planning administrator wouldn’t comment on specific costs because every home’s hookup charges are different.

Last summer, a neighbor who hooked up to city water in 2005 wrote the city, pleading unsuccessfully to find some wiggle room in its remote meters ban.

“Most of the residents on our street are totally dry again, clearly because of the drought situation, which promises to only get worse,” Pat Rhea wrote. “Our neighborhood is desperate for water, many have livestock, and trucking in the water is not a good option.

“When there is a dire need ... and our community is definitely unique for sure ... ‘dire’ does not even begin to describe the situation out there!”

10 years of hauling

Living 2 miles uphill from pavement on a washboarded dirt road, longtime Santa Rita Mountain foothills resident Mike Bong has learned to live with his dry well.

He’s been hauling water for the last 10 years.

Every two weeks, he drives his pickup, with its 500-gallon water trailer, 4.4 miles to a watering station in unincorporated Vail. There, a line of about 30 spigots serves customers who lack access to municipal water supplies. Bong pays $40 to $50 a month.

“Most people moved up here because we pretty much want to be left alone,” said Bong, a foreman for Faulk Electric Corp. “I don’t hear sirens at night. On the Fourth of July, you can watch every fireworks display in town.”

For the past two years, he’s also been hauling water five months a year for a neighboring rental house owned by his mother-in-law, Sandy Whitehouse, because that 400-foot-deep well, 80 feet shallower than his, is dry. Another neighbor’s well recently dried up, forcing the couple to move away.

“I can’t get out of my house what I paid for it,” he says. “But I literally wouldn’t move. I couldn’t handle living in the city.”

Tom McKeon, who rents Whitehouse’s home, moved from Corona de Tucson.

“I used to live in town and had endless water,” he says. “Here, you’ve gotta be careful about what you do. I don’t take showers here. I take showers at a friend’s house.”

His ex-wife and daughter, who live in the house, do shower at home, he says.

Since the mid-1990s, about 45 families have put in wells along Copper Cut Trail, the main road leading into this area from Sahuarita Road, state water officials say.

Bong says he doesn’t know who to blame for the dry wells because there are so many variables — an aggregate mine operating further uphill, the continued arrival of new neighbors and the drought, to name a few.

“The point is, who is going to fix it, and how? Nobody has an answer, and nobody wants to take responsibility,” he says.

“My theory is that they’ll run the water until it’s dry, then they’ll worry about it.”