On a recent Tuesday, a trio of Pima County victim advocates went to assist police with a possible neglect case involving an older woman who was blind and spoke only Spanish.

The woman's daughter had arrived to help translate and was distraught, saying the person who was supposed to be caring for her mother had taken steps to keep the daughter away. She said she'd long wanted to help her mother but hadn't known what to do.

One of the advocates worked with the mother, speaking Spanish and giving her water in the afternoon heat. A second comforted the daughter, speaking in soft tones and offering tissues while just listening.

By the time the exchange was over, both mother and daughter said they felt supported and hopeful. It was just one everyday example of the myriad of situations the advocates respond to, "to help out in the community with folks suffering a loss or tragedy or crime," said Virginia Rodriguez, victim services director for the program run by the Pima County Attorney's Office.

But the program's volunteer force is down to nearly half its pre-pandemic size, and the County Attorney's Office is looking to rebuild its ranks as the need to support victims of crime grows.

The office's Victim Services Division was established in 1975, becoming the first in the country to provide comprehensive assistance to victims of crime both at the scene and while navigating the criminal justice process. There are a handful of advocates on staff.

For years, the office relied on a force of roughly 100 volunteer advocates to help keep the division staffed 24/7, but these days, there are about 55 volunteer advocates, Rodriguez said.

And, with a rise in violent crime in Pima County, calls for advocates are increasing.

Crisis support

Victim advocates provide in-person support and resources to help empower people seeking justice or recovering from trauma.

The division just completed its first training of 2022, which started in February and ran two nights a week for six weeks. With COVID-19 restrictions still in place, the training — which is usually open to members of the public — was restricted to prospective volunteers only.

With a second and unrestricted training scheduled for September and staffers hitting the streets in August to get the word out, Rodriguez hopes for a full class of advocates to help fill in the gaps in crisis coverage that have resulted due to decreased numbers.

Pima County's victim advocacy program was the first and remains one of the only in the country that includes both court support and on-scene crisis support, Rodriguez said.

"It's very important to the community. Our own community members come together from all walks of life in this common thread to help victims of crime," she said.

During their six weeks of training, advocates learn about working with victims of stalking, domestic violence and child abuse; providing death notifications; cultural awareness and more.

During a recent session on working with children, Victim Compensation Fund coordinator Rosanna Cortez spent two hours walking attendees through tactics that take into account the different impacts trauma can have on a person, to help them sensitively approach and assist a child who was the victim of or witness to a crime.

Cortez, who previously worked as an advocate for 18 years, was among a group of Pima County Attorney's Office advocates who provided support and help to first responders following the 9/11 terror attacks in New York City.

On Jan. 8, 2011, Cortez assisted victims of the Tucson mass shooting involving Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords and others, and in 2017, Cortez led a team of PCAO advocates who traveled to Las Vegas to support victims of the Oct. 1 mass shooting.

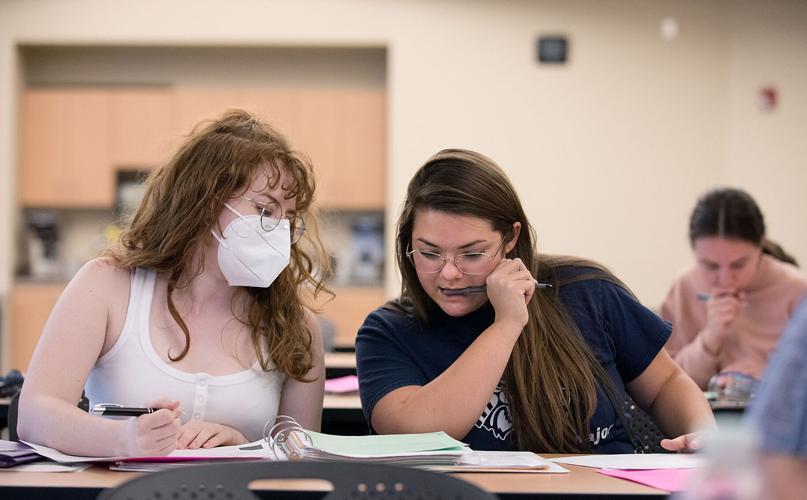

Eebee Schaefer, left, and Tatiana Calderon work together on an exercise during a Pima County Attorney Office's Victim Services Division training at the Tucson Police Department Miracle Mile substation.

Cortez started the training session by talking about Adverse Childhood Experiences, also known as ACE, which include things like physical and emotional abuse, neglect, caregiver mental illness and household violence.

"Given the statistics, we know people in this room have been impacted by adverse childhood experiences," she said. "Do whatever you need if you need to step out, but you know the drill. Someone will step out and check on you and make sure you're OK."

Helping children who are suffering

Cortez provided the group with statistics and facts surrounding child abuse in the form of a multiple choice quiz, with participants using noisemakers to indicate their selection.

From there, they moved onto resilience-building techniques to help empower children and provide them with a renewed or new sense of confidence. They talked about the neuroscience behind childhood brain development and what tools advocates can use to support a child's needs during a time of trauma.

"You may believe that you can help but might not really know what to do. We're hoping by the end of night, you have a few simple strategies and tools to act on if you were to encounter a child tomorrow," Cortez told the group.

Attendees watched videos, participated in discussions and role played ways to work with children in the aftermath of trauma, with Cortez explaining that advocates are mandated by law to report suspected abuse.

"This isn't theoretical, this is something we often have to do," she said. "Young kids disclose incidentally often and they may not realize they're disclosing. If you're the person they pick to tell, you've got to know what to do."

Cortez also taught prospective advocates appropriate things to say to a child when their loved one dies, along with things not to say. She also talked to them about drawing as an intervention tool and how it can be a helpful way for kids to express their feelings.

At the end of the session, attendees split into two groups to practice working with a drawing. Established victim advocates in attendance took on the roles of children and worked with prospective volunteers to practice asking questions about the child's drawing.

"We want you to recognize that every person in the room has the ability to help a child who is suffering," Cortez said.

Forming connections

While the bulk of volunteer advocates seem to be seniors and students, there's a wide diversity in age, political views and language, Rodriguez said. "We get people from all sorts of walks of life."

She said the volunteer force represents the "full spectrum of points of view" but has a built-in camaraderie thanks to the shared experiences.

"Riding along in that van, they can get somebody that grew up in the 1960s paired with someone who is a member of Generation Z," she said. "What other place can you have that face-to-face contact and communication that forms those connections?"

Ryan Edwards uses a radio during victim advocate training for the Pima County Attorney Office's Victim Services Division at the Tucson Police Department Miracle Mile substation.

Now that county pandemic restrictions have been lifted, advocates are back in the field providing crisis response and Pima County's courts have opened up.

Rodriguez hopes to expand the program's reach. But that means doubling its volunteer pool so that advocates can provide 24/7 crisis response.

The minimum commitment per month for volunteers is 20 hours, with a variety of duties to choose from ranging from going out on crisis calls, attending court and helping out at the office.

The current greatest need is help with crisis call response, Rodriguez said. As of now, there aren't enough people to regularly cover the overnight shift, which runs from 10:30 p.m. to 6:30 a.m.

"We'd love to have folks on those shifts, but also having people in the office in the afternoon covering court is very helpful," Rodriguez said. "Crime has gone up and our law enforcement partners are short-staffed. We appreciate when they call us and trust that they call when they need us."

Last year was a record-breaking year for homicides in the city, with 93 homicides reported, according to the Tucson Police Department. The former record was set in 2008 with 79 homicides.

Having relationships with law enforcement is critical to the program's success but also to having a healthy society in general, Rodriguez said.

Small gestures can mean large rewards

During that recent Tuesday shift, longtime advocate Leo Quesada teamed up with Nancy Davis and Angelica Santamaria, who both have less than a year of experience under their belts. Quesada, who works full-time for Southwest Gas and sits on the board of 88-CRIME, has been a volunteer advocate for 32 years.

Their first call — the possible neglect case — came in minutes after the start of their 5:30 shift, with Tucson police officers calling them to assist in the situation, which also involved a family dispute.

Santamaria, who said she speaks a little Spanish, walked over to the mother, who was seated in a chair, and dropped down to her level. Davis came to the side of the daughter, speaking softly and crouching on the ground so she was at eye level, offering water and, when needed, tissues.

Quesada, who was there mostly to supervise, stood back and watched the pair of newer advocates as they offered information about Adult Protective Services, resources for older adults on a limited budget, and the public fiduciary.

By the time the exchange was over, the daughter's tears of distress had dissipated, and she told Davis and Santamaria that she felt for the first time like someone listened to her side of the story and believed her. Davis smiled warmly at the young woman, tenderly touching her arm as they said their goodbyes.

Davis, a University of Arizona graduate and military wife, returned to Tucson with her husband roughly four years ago.

"I'm used to helping our neighbors in the military," she said. "This fills that void."

On Davis' first ride along, which was also with Quesada, she learned they had a Tucson connection. Nineteen years ago, Quesada was the advocate that responded to the hospital to help provide support to the family of Brandi Fenton, who was killed in a car crash. Davis is close friends with the Fenton family.

Santamaria will soon be training to be a pediatric nurse. She works in radiology at a local hospital and previously spent time working as a Certified Nursing Assistant and then in the military. Santamaria found victim services when looking for volunteer opportunities that would fulfill her nursing school application requirement.

"I wanted to do something I like. My dad is a retired detective and he told me about victim services and what they do," she said.

Santamaria's required volunteer hours have long been fulfilled, but she has no plans to stop working as an advocate.

Quesada, who started volunteering as an advocate in the fall of 1989, knows the feeling. What started as a one-off ride-along at the suggestion of two advocates he knew through his work as a volunteer with TPD has turned into a way of life for Quesada and his family.

"They showed me the ropes that night and I really got hooked," he said. "I've been here ever since."