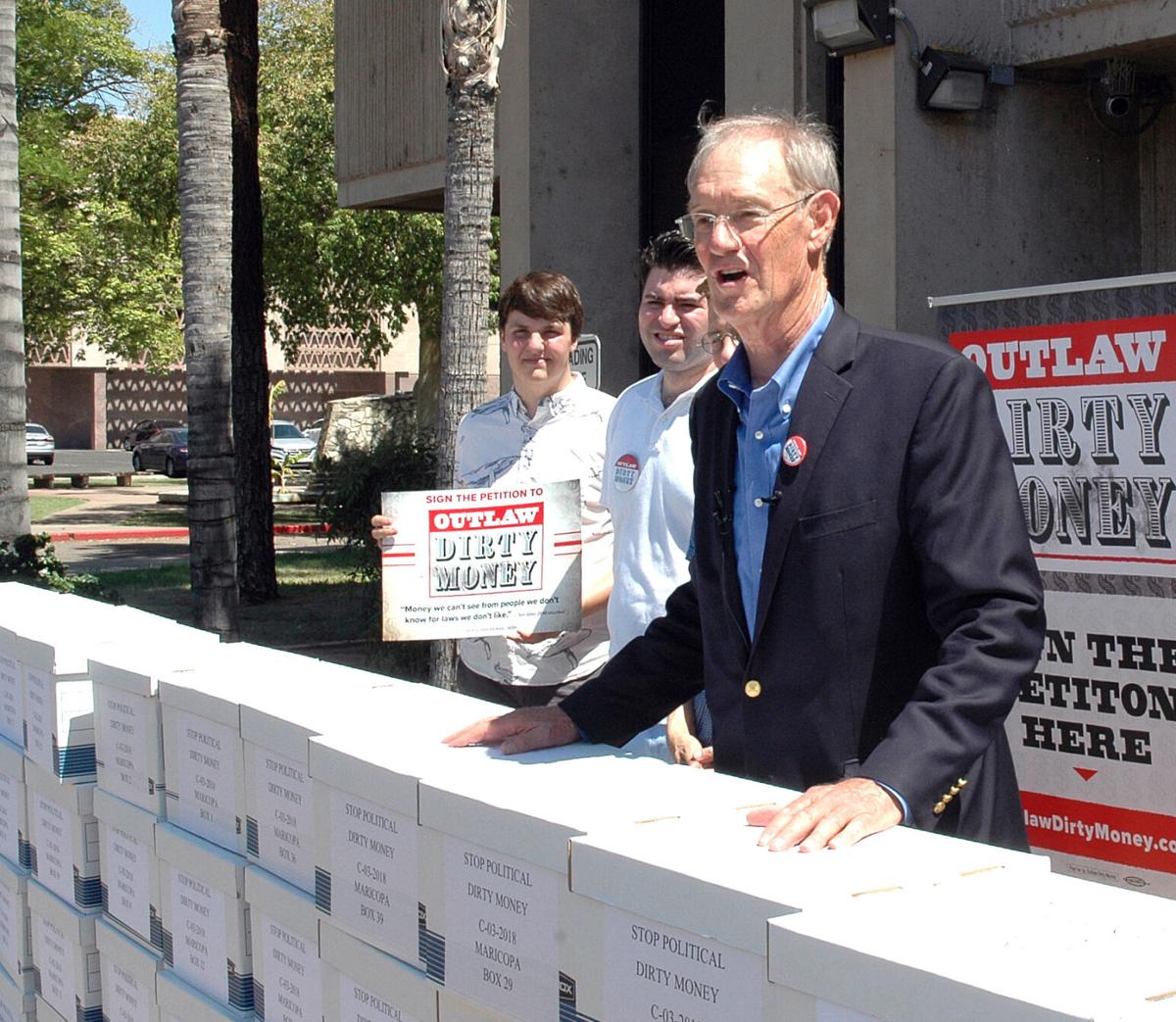

PHOENIX — Former Attorney General Terry Goddard is making a third — and, he hopes, finally successful — pitch to put a measure on the Arizona ballot to outlaw so-called “dark money.”

The initiative would require the public disclosure of the true source of donations of more than $5,000 spent by organizations on any candidate or ballot measure. Current law exempts these “social welfare” organizations from having to list their contributors.

Goddard’s effort is worded to cut through any effort to hide the identity of the actual original donor by having the cash moved through a series of groups, a process Goddard calls “laundered.”

A similar 2018 effort he led failed after foes challenged some of the 285,000 signatures collected. And, under the terms of a law approved by the Republican-controlled legislature, the judge had to strike all of the signatures gathered by paid circulators who did not respond to a subpoena.

In 2020 Goddard moved to an all-volunteer effort to circumvent that problem. But the signature gathering faltered during the COVID-19 pandemic which included, for a period of time, a stay-at-home order.

This time around Goddard is choosing a course that may make reaching the goal easier.

First, he said, any paid circulators will be local and not subject to the same automatic disqualification provisions. More important, it is being proposed not as a constitutional amendment but a change in state election laws.

That difference is crucial. It takes 356,467 valid signatures to put a constitutional change on the ballot; a statutory amendment needs just 237,645 by the July 8, 2022 deadline.

There is a danger going that route. Even though the Voter Protection Act bars lawmakers from altering or repealing statutory changes, they may find workarounds to effectively undermine the provision. But Goddard said he believes the language of the measure is tight enough to avoid tinkering by the Republican-controlled Legislature which has approved measures designed to allow for donors to political efforts to hide their identities.

The heart of the measure is what Goddard calls the “right to know.”

Current law makes public any donation of $50 or more directly to a candidate or an initiative campaign. But those laws do not cover “independent expenditures,” campaigns by groups not legally connected to the candidate or campaign that urge voters to support or reject an individual or an issue.

These are usually run by groups organized under the Internal Revenue Code as “social welfare organizations.”

They are free to spend money on political issues and must disclose how they use their cash. But the Republican-controlled legislature has approved laws that they need not disclose their donors.

And there can be a lot of money involved.

In 2014, for example, American Encore spent more than $1.4 million on Arizona races. And while the group originated with an organization founded by the Koch brothers, there is nothing on the record of who put up those dollars.

What is known is some of that American Encore money helped Republican Doug Ducey defeat Democrat Fred DuVal in the gubernatorial race. Overall, outside groups spent more than $8 million on Ducey’s behalf in that campaign, outstripping the $7.9 million Ducey spent himself in funds that came from donors whose identities he was required to disclose.

The initiative spells out that once any statewide campaign spends or accepts $50,000 — $25,000 for local or legislative races — it has to start filing public reports of the source of the funds received. That means providing the name, mailing address, occupation and employer of anyone who has contributed at least $5,000. And that includes not just who is the direct donor, but where that entity got the money.

Any group spending money on Arizona races that can’t trace back and identify the ultimate source of the cash has to give the money back, Goddard said. And he if they use the money anyway on media campaigns, they are subject to fines equal to three times the amount of the unidentified cash.

The move will get a fight — and not just from groups that have a habit of making independent expenditures.

Sen. J.D. Mesnard, R-Chandler, has been one of the champions at the Capitol for what he says is the constitutional right of people to participate in the political process and to do so independently.

“People should be able to support the charities, the causes that are near and dear to their heart without fear that they’re going to be doxed, especially in this day and age when we’re seeing that happen more and more,” he said.

“Doxxing” refers to the practice of revealing someone’s personal information on the internet, usually for malicious purposes. Mesnard said that can lead to efforts to ruin people financially or have customers boycott a business.

He acknowledged that existing law requires disclosure of donations directly to candidates or ballot measures.

“Absolutely, we need to know who is behind a candidate because you have financial conflict-of-interest considerations,” Mesnard said. “Those types of things don’t exist when it’s an independent entity exercising its right to free speech.”

But Goddard said there really is no difference, whether the cash goes directly to the candidate or to another group working on behalf of the candidate, even if there is no formal coordination. He said the U.S. Supreme Court has said the First Amendment right to speech and participate politically doesn’t entitle confidentiality.

“If you’re a political contributor, you don’t have a right to hide,” he said. Goddard also said this isn’t a liberal-conservative thing, citing a 2010 quote from then-Justice Antonin Scalia in a case involving disclosure of petition signatures.

“For my part, I do not look forward to a society which, thanks to the Supreme Court, campaigns anonymously . . . hidden from public scrutiny and protected from the accountability of criticism,” justice Scalia wrote.

Goddard also pointed out the measure protects the identities of small donors, with an exemption for those who put less than $5,000 every election cycle into political campaigns. What’s left, he said, is “a pretty rarefied area” of those who have the resources not only to give but also to protect themselves.

Even with that, the initiative does contain a provision that allows those who believe they or their families would be subject to “serious physical harm” to petition the Citizens Clean Elections Commission for an exemption from disclosure. But he said that doesn’t shield businesses that use their funds to influence election through independent expenditures.

“I don’t think a corporation can be physically harmed,” he said.