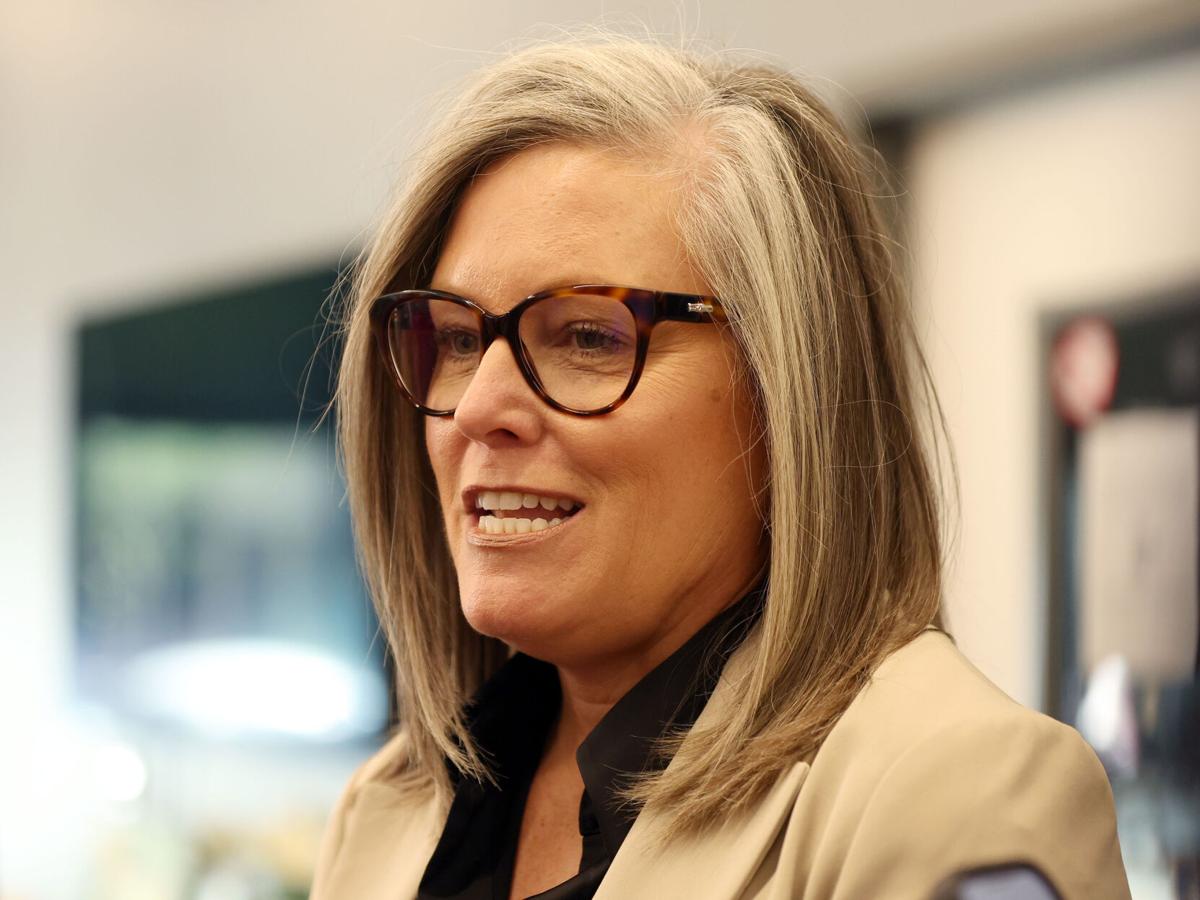

PHOENIX — Gov. Katie Hobbs is trying to get the Court of Appeals to overturn a judge’s ruling that her actions to get around her fight with the Senate over director nominations are illegal.

And her case turns on arguments by Andrew Gaona, her attorney, that she “shall’’ make nominations doesn’t mean she “must.’’

In new court filings, Gaona argues that Maricopa County Superior Court Judge Scott Blaney was legally off base earlier this month in concluding she acted illegally in naming 13 individuals as “executive deputy directors’’ to run state agencies after the Senate would not confirm her picks. The judge said the governor “willfully circumvented’’ the process of legislative review.

Hobbs said after Blaney’s ruling she would appeal rather than negotiate with the GOP.

But Gaona told the appellate court that Hobbs had to act to ensure that someone was running the agencies after the Senate created “a drawn-out political circus,’’ slow-walking some nominations and “concerned more with partisan talking points than the serious consideration of executive nominations.’’

Hobbs needs a quick answer from the appellate judges.

Blaney has scheduled an Aug. 14 hearing to decide whether to order the governor to send the names of her nominees to the Senate or risk being found in contempt.

But more than that is hanging in the balance.

Gaona argues that leaving Blaney’s ruling as is would “create a massive cloud of uncertainty around everything that the executive deputy directors in 13 state agencies have done,’’ dating all the way back to when they were first appointed in September 2023. That could provoke legal challenges.

But the bigger issue, he said, is the precedent it would set.

As Gaona sees it, allowing the Senate to throttle gubernatorial nominees — refusing not just to confirm them but leaving them in legal limbo without even considering them — would violate constitutional separation of powers.

“The Senate could shackle executive operations at its want and whim,’’ he wrote. “This decision cannot stand.’’

Arizona law requires a governor to submit the names of those she has picked to run state agencies to the Senate for confirmation.

Any who are rejected outright cannot serve and the governor must name someone else. If the Senate fails to act, the pick can stay in place only for a year.

After Hobbs took office in 2023, Senate President Warren Petersen set up a special Director Nominations Committee, departing from the usual procedure where a governor’s picks were reviewed by standing committee with expertise in a particular area like health or finance. And Petersen tapped Sen. Jake Hoffman, R-Queen Creek, founding member of the conservative Arizona Freedom Caucus, to chair it.

Hoffman, in turn, said he intended to do a deep dive into each pick, arguing that state agencies set policies that can have the effect of laws. But Gaona said that the panel went far beyond.

Consider, he said, the governor’s nomination of former state Sen. Martin Quezada to head the Arizona Registrar of Contractors which licenses and oversees those involved in construction, something he said is a non-political job.

“Committee members asked him about (among other topics) transgender people in sports, face masks during the pandemic, white nationalism, mass shootings, antisemitism, border security, empowerment scholarship accounts, critical race theory, and Israeli-Palestinian relations,’’ Gaona told the appellate court.

“Of course, none of this had anything to do with Mr. Quezada’s fitness to lead the Registrar of Contractors — a job he’d dutifully fulfilled for nearly four months until the DINO Committee voted against his appointment on party lines,’’ he said. Hobbs withdrew the nomination, making Quezada “the victim of a Senate committee concerned more with partisan talking points than the serious consideration of executive nominations.’’

The committee failed to even take up 13 other nominations. So Hobbs last year withdrew their names from consideration and used a maneuver to instead have them named “executive deputy directors’’ of those same agencies, leaving them in charge as none of those agencies has an actual director.

It was that act that Blaney concluded broke the law by skirting the legal requirement that state agencies be headed by those who actually have been confirmed by the Senate.

In his ruling, Blaney acknowledged Hobbs’ concerns. But he said that didn’t change anything.

“The governor’s frustration with a co-equal branch of government — even if that frustration was justified — did not exempt her director nominees from Senate oversight,’’ he said. And he cited state laws spelling out that the governor “shall nominate’’ department heads and “shall promptly transmit’’ the nominations to the Senate.

But Gaona is urging the court to read that word “shall’’ not as a mandate on the governor — at least in this kind of situation — but as “directory.’’

The key, he told the appellate judges, is that nothing in the law saying that Hobbs “shall nominate’’ agency heads holds any sort of penalty for her not acting within a given period of time.

Gaona said it would be one thing if the law said the failure of the governor to nominate directors by a certain deadline stripped her of the power to do that. This does not do that.

By contrast, Gaona said, there is a state law that says if the governor does not fill a vacancy on the Commission on Appellate Court Appointments within 60 days, then the chief justice gets to make the pick. The same is true of vacancies on a fire board which has to fill vacancies within 90 days or the responsibility falls to the board of supervisors.

Since the Legislature imposed no such time limit, Gaona told the appellate judges, it must be that the omission in this case was intentional — meaning that “shall’’ can’t be interpreted as a mandate.

And he said there’s another reason that “shall’’ can’t be interpreted as a mandate.

Gaona told the appellate judges that even if Hobbs could be forced to send her picks to head state agencies to the Senate, state law also gives her the power to withdraw any nominations — immediately.

“Any mandatory duty to nominate people by any date would thus be meaningless because the governor could comply with the duty and then withdraw the nominations, leaving the Senate in the same position that it’s in now,’’ he said.

Gaona also said requiring the governor to act by a specified deadline, as he said Blaney reads the law, creates logistical problems.

He said there are more than 100 vacancies for positions that require Senate confirmation. He said the lower court ruling could allow the Senate to sue the governor to coerce her to make picks of certain agencies first, denying the governor the time she needed to properly vet people.

No date has been set for the appellate court to consider the governor’s arguments.