Arizona tribal leaders, advocates, community members and organizations are celebrating the 75th anniversary this month of Indigenous people in Arizona earning the right to vote.

“The power of the Native vote is 75 years strong,” said Maria Dadgar, executive director of the Inter-Tribal Council, during a celebration honoring the anniversary of Native voting rights in Arizona held at Gila River Resorts & Casino — Wild Horse Pass in Chandler on July 14.

Dadgar said the celebration was to highlight the Indigenous people who fought long and hard to win the right to vote, and the celebration is to commend all the work that Indigenous people do and continue to do to protect that right.

Arizona has one of the largest Native voting populations in the country, with more than 305,000 of voting age, according to the National Congress of American Indians. Indigenous people make up 6% of Arizona’s overall population.

“Arizona has been described as ground zero for restrictive voting laws since the last election,” said Gila River Indian Community Gov. Stephen Roe Lewis. Even after gaining the right to vote in 1948, Native voters still face obstacles to casting their ballot, from voter suppression to racial discrimination.

“It’s no accident that these laws targeted our tribal communities,” Lewis said. “Our community members show up on Election Day. We show up because we know that it matters who sits in those state offices.”

Gila River Indian Community Gov. Stephen Roe Lewis speaks during a 2019 field hearing in Phoenix on voting rights and election administration issues facing Arizona and the Native American community.

Indigenous people in Arizona did not gain the right to vote until July 15, 1948, after the Arizona Supreme Court struck down a ban originally outlined in 1924.

In Arizona, the fight for Native voting rights started when Gila River Indian Community citizens Peter Porter and Rudolf Johnson filed a suit in November 1924, advocating for Indigenous people in Arizona to have the right to vote in state elections.

That attempt failed when the Arizona Supreme Court determined that, although Indigenous people of tribal nations in Arizona were state residents, they could not vote because they were considered under federal guardianship.

For the next 24 years, Indigenous people did not have the right to vote until Fort McDowell Yavapai tribal citizens Frank Harrison and Harry Austin tried to cast their votes in 1948.

Their goal was to vote for Arizona leaders who would support their efforts to provide for senior citizens and families, but the Maricopa County recorder turned them away.

They soon filed a lawsuit in hopes of overturning the Arizona Supreme Court’s decision from 1924, and on July 15, 1948, the state’s high court ruled in favor of Harrison and Austin.

“In a democracy, suffrage is the most basic civil right since its exercise is the chief means whereby other rights may be safeguarded,” Arizona Supreme Court Justice Levi Udall wrote in the opinion that established Indigenous people’s right to vote in the state.

“To deny the right to vote, where one is legally entitled to do so, is to do violence to the principles of freedom and equality,” he said.

Dadgar said Indigenous people fought long and hard to win their right to vote in 1948, yet they still face many obstacles and barriers when exercising their rights today.

Joshua Gonnie, a Navajo voter, wore an "Every Native Vote Counts" shirt to cast his ballot in Phoenix in the 2020 presidential election.

“It is our hope that by meeting annually to celebrate the Native Right to Vote event, we will continue to stimulate dialogue in Arizona in a positive direction toward improving access to voting for all citizens,” she said.

‘We have come so far’

Several tribal leaders, advocates, community organizers, youth and community members gathered to honor the efforts of all 22 tribal nations in Arizona to protect and honor the Native right to vote.

Lewis said it’s important to acknowledge that when Indigenous people gained the right to vote in 1948, they had been considered U.S. citizens for only 24 years, but it would be another 20 years before they gained access to the Bill of Rights.

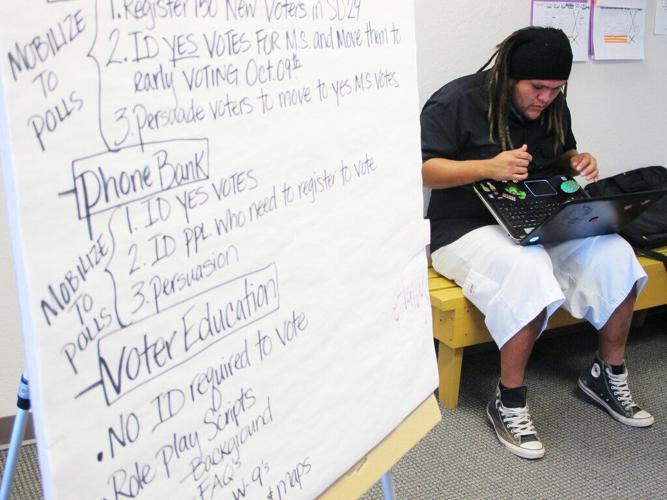

A volunteer for the Native American Voters Alliance works on his laptop, next to a road map for getting out the vote.

“Protecting our voting rights doesn’t end once you leave the borders of our sovereign nation,” Lewis said. “Protecting our rights on the reservation is just as important as protecting our rights off the reservation.”

For instance, Lewis said the water rights of the Gila River Indian Community were stolen from them 150 years ago.

“That historic theft occurred at a time when we couldn’t vote,” Lewis said. “When we didn’t have those basic civil rights to be able to advocate and to vote for leaders that would protect our sovereignty and our water rights.”

The fight to gain the right to vote came at a tumultuous time for Indigenous people, Lewis said, because it was during a time that tribal governments, land and culture were all being questioned.

“At a time when we had to fight for our place in the country that formed around us and on our lands,” Lewis said. “In so many ways, we have come so far since that time, but we all know we’re still fighting.”

Lewis said it’s not too early to start organizing and educating Indigenous communities about the 2024 election season. He said the stronger the Native vote becomes, the louder Native voices become.

Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community Tribal Council Member Mikah Carlos said it’s important for Indigenous communities to unite like this because they have been fighting hard to obtain their basic civil rights.

“Sometimes it feels like we’re not making any progress because we’re continuously having to fight,” Carlos said, which is why “we celebrate to remind ourselves that we do have victories.”

Even though the work is not done and Indigenous communities still have to fight, Carlos said the Native vote is powerful.

“I think if our vote wasn’t powerful, they wouldn’t be trying so hard to take it away,” she added.

The Young River People’s Council from the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community also attended the celebration. Youth Advisor Sommer Lopez said she was happy to bring them out because it’s important for them to learn about Native voting rights.

“It’s important to celebrate it for us because it reminds people that it was not that long ago,” Lopez said. “It’s something that we should remember because there was a lot of hard work and sacrifice put into it.”

Lopez said they do a lot of outreach within their community to get more people registered to vote and educate the youth so they’re aware and prepared for voting.

When Lopez learned that Indigenous people in Arizona only gained the right to vote in 1948, she said she was shocked because she knew that her non-Indigenous peers didn’t have the same type of history.

Lopez said for Indigenous people, it’s not even their ancestors; it’s more like their grandparents because it was only 75 years ago.

Watch now: Tucson City Council members unanimously approved a motion at its April 18 meeting to give ancestral land near the base of “A” Mountain to the Tohono O'odham Nation.