Tribal advocates told a Senate panel this week the federal government’s effort to fund expanded broadband infrastructure in Indian Country overlooked a fundamental issue.

Many tribes did not have the broadband access needed to apply for the funding that would let them improve broadband access.

Information about the first round of grants was available only online, and tribes were encouraged to apply online in a 90-day window during the pandemic. The upshot, said Matthew Rantanen, was that only about half of all eligible tribal communities applied for the funding.

“Some of the tribes didn’t get enough of the information about it or didn’t have access already, which we know they don’t have access to broadband,” said Rantanen, the co-chair of the National Congress of American Indians Subcommittee on Technology and Telecommunications.

His comments came during a Senate Committee on Indian Affairs roundtable discussion Wednesday on the National Telecommunications and Information Administration’s Tribal Broadband Connectivity Program, a multibillion-dollar program aimed at increasing digital equity in tribal communities.

Originally created as a $980 million program in the fiscal 2021 budget, the program received another $2 billion infusion as part of the bipartisan $1.2 trillion Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act that passed in November.

The first phase of the program set aside up to $500,000 for each of the 574 federally recognized tribes that they could seek to use for broadband projects. Paper applications were accepted, but the program’s online FAQ page says that “NTIA prefers that applicants use Grants.gov to submit their applications.”

Not only was it difficult for some tribes to access information on the grants, but the short timeframe during a pandemic made it hard for many tribal councils to meet and discuss their applications, said Rantanen, who is also on the board of Arizona State University’s American Indian Policy Institute.

Access is not the only issue dogging the program: Government agencies cannot agree on the scope of the problem.

Federal Communications Commission data from 2019 showed that fixed broadband services reached 95.6% of the nation as a whole, but just 79.1% of people on tribal lands — and only 46.5% of tribal households had adopted these services. The FCC bases its report on geospatial data collected by broadband providers showing where broadband currently exists and could potentially exist.

But a 2018 report by the Government Accountability Office said the FCC data overstates tribal broadband availability, by lumping in areas where infrastructure could be expanded with areas where broadband is available.

Sen. Brian Schatz, D-Hawaii, said the data can lead lawmakers to believe the situation is less severe than it actually is.

“We have actual bad data, which leads policymakers … to engage in magical thinking about who has broadband connectivity,” said Schatz, the chairman of the committee.

Manuel Heart, chairman of the Ute Mountain Ute tribe in Colorado, said that rural areas were especially affected by lack of connectivity during the pandemic.

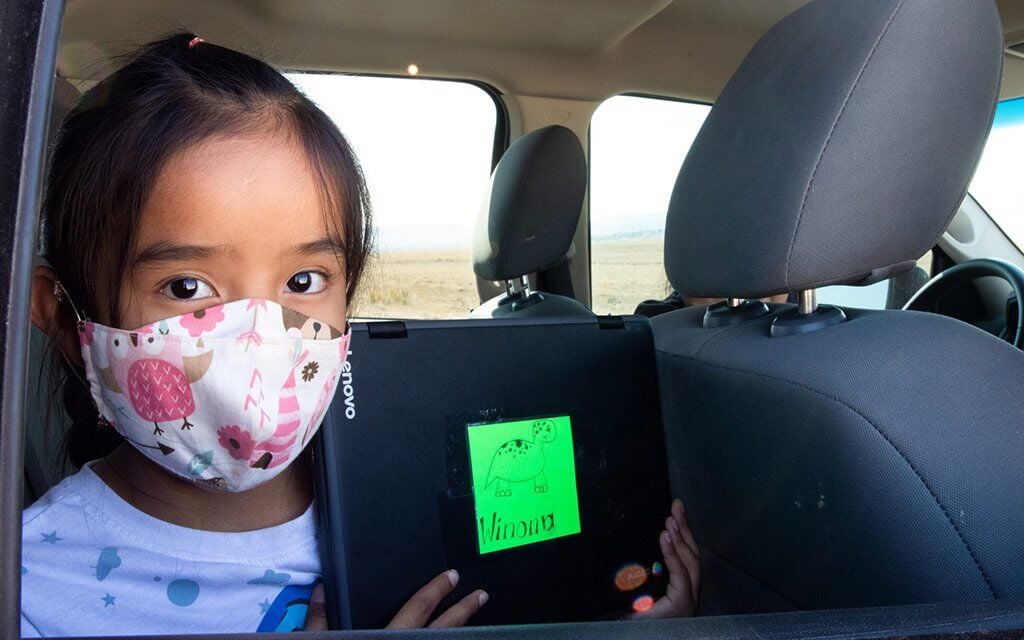

“We’ve had to put in some hotspots where parents have to bring their students to a parking lot just to access internet” when schools were shut down by COVID-19, he said.

The NTIA said it has approved just five of the 280 tribal applications for the program so far, including one for the Yavapai-Apache Nation in Arizona. But not every tribe had major issues with the grant application during the pandemic.

Walter Haase, the general manager of the Navajo Tribal Utility Authority, said the Navajo Nation’s self-funded infrastructure following an Obama-era grant has greatly improved the tribe’s broadband access. That allowed it to avoid many of the problems with the online application format that hindered other tribes, he said.

Internet challenges on sprawling Navajo lands are steep. Navajo Nation President Jonathan Nez told a House committee in 2020 that New Jersey is one-third the size of the Navajo Nation but had more than 1,300 communication towers compared to the tribe’s 1,000 towers – most of many of which were on the borders of the reservation.

But Haase said forming public and private partnerships and creating nonprofit entities may help other tribes develop a more robust broadband system like the Navajo.

“We’ve made tremendous progress forward, and having that fiber backbone throughout the Navajo Nation … gives us an upper hand in solving the problem,” he said.