The future of affordable housing in Tucson should be centered on high-capacity transit, like fast-moving bus and light-rail systems, planners say.

And three planned affordable-housing complexes near the streetcar route are just the beginning.

As a low-wage community, Tucson has many families without any vehicle or with just one vehicle, even if more than one household member works, said Marilyn Robinson, community planner and associate director of the Drachman Institute in the University of Arizona’s architecture school.

“Given that, we need to do a better job of providing a stronger transit network,” she said. “What we should be looking at is, how are we going to accommodate a whole range of incomes along the streetcar (route) and other high-capacity transit corridors?”

Demand for housing near transit routes is growing in Pima County, according to a new housing demand study commissioned by the Drachman Institute and funded by the Arizona Department of Housing. Nearly 65,000 households, mostly renter households, have a preference for housing with easy access to transit, and that figure is expected to reach nearly 96,000 households over the next three decades, the findings show.

The full results of the affordable and mixed-income housing demand study — including an assessment of dozens of potential transit station locations in Tucson — will be discussed at an Aug. 15 presentation at the Drachman Institute.

When families can rely on transit for the daily commute, cost of living and quality of life can improve dramatically for those struggling with vehicle payments, maintenance and fuel costs, planners and housing advocates say.

“The more transportation options you provide, the more freedom people have to make housing choices,” said Jeremy Papuga, city of Tucson transit director and former transit services director for the Pima Association of Governments.

With momentum from the streetcar still fresh, planners hope to focus attention on the need for smart planning along with potential high-capacity transit routes.

Maintaining affordable and mixed-income housing there not only helps those residents, but boosts patronage and revenues for the transit services. And when transit systems function reliably and efficiently, residents of all income levels want to use them, Robinson said.

“It’s a win-win,” she said.

The 45 percent threshold

Finding affordable housing is a major challenge for Tucsonans living in poverty, who today make up more than one-fifth of the metro area’s population. The Star’s 2013 “Losing Ground” series on poverty noted thousands are on the waiting list for Section 8 housing and many poor families must resort to aging, deteriorating homes. Between 50,000 and 80,000 units, up to 18 percent of the city’s housing stock, are more than 50 years old.

Too often, low-income housing is equated with use of cheaper building materials or cheaper land on the outskirts of town — but those cost savings can evaporate when projects are located miles and miles from places of employment, recreation or commerce, advocates say.

After housing, transportation is the second-biggest expense for low- to moderate-income households, Robinson said.

To be affordable, housing and transportation costs combined should account for less than 45 percent of household income, but in Pima County, the average household spends nearly 55 percent of its income on transportation and housing, said the Center for Neighborhood Technology’s searchable affordability index.

In east Pima County, some ZIP codes spend more than three-quarters of their household income on those expenses, which can have a devastating impact on quality of life, advocates say.

TAX CREDITS

Affordable housing near public transit are now more likely to secure federal low-income housing tax credits, the biggest source of funding for those projects, planners say. Arizona developers are expected to get $15.3 million in competitive tax credits for housing developments proposed this year.

That includes two Pima County low-income housing proposals near the streetcar route: The historic Downtown Motor Lodge at 383 S. Stone Ave., to be converted into housing for low-income veterans and others, got $934,000 in federal low-income housing tax credits. Another proposed Stone Avenue affordable-housing complex, Rally Point Apartments at 101 S. Stone, got $464,000 in tax credits.

The Gadsden Co., has an agreement with the city to develop a 160-unit, $17.5 million low-income housing complex at the west end of the streetcar route. Gadsden also has applied for noncompetitive tax credits through U.S. Housing and Urban Development, said developer Adam Weinstein.

The project is adjacent to Gadsden’s Sentinel Plaza development for very low-income seniors. The planned West End Station is considered “workforce” housing, geared toward working families earning 50 percent to 80 percent of area median income, he said.

Subsidies for transit-oriented development are passed on to tenants “because they’re able to put more of their income toward rent, school, other things, rather than having that eaten up by maintaining one or two vehicles,” he said.

LONG-TERM PLAN

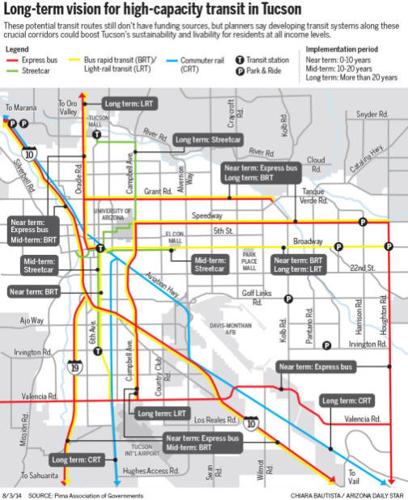

In the coming decades, Tucson could see an expansion of the 3.9-mile streetcar loop and the addition of dedicated, rapid bus lanes stretching north to Tangerine Road and East to Houghton Road. A light-rail system could extend down Sixth Avenue and north toward Oro Valley. A 2009 plan from the Pima Association of Governments, or PAG, mapped out these potential high-capacity transit routes, including a possible commuter-rail service, utilizing or parallel to the Union Pacific Railroad, to major employers like Davis-Monthan Air Force Base and Tucson International Airport.

“It was kind of a wish list. If we had all the money in the world, these are the corridors that would benefit from high capacity,” said Papuga, formerly of PAG. “Hopefully, we’ll be able to use the momentum from our current streetcar to start more high-capacity transit.”

PAG will soon update the 2009 long-term plan, which imagines transit networks in the year 2040 and beyond.

But even the near-term plans aren’t a given, RTA director Farhad Moghimi said via email. Funding sources haven’t been identified yet for any of those projects.

The $197 million streetcar project got $63 million in federal TIGER grant funding. But future transit developments will need new funding streams, Papuga said.

“It’s harder and harder for communities to rely on federal money to build these projects,” he said. “In order to expand our high-capacity transit plan, my belief is we will have to find a way to fund it locally or through private investment.”

PROTECTING AFFORDABILITY

Over the next year, the city will schedule public meetings to gather community input on long-term plans for housing developments throughout Pima County, said Sally Stang, director of Tucson’s Housing and Community Development Department. The public forums will solicit opinions on potential locations for new housing, including infill development in higher-density areas and along future transit routes.

“Those are the conversations we’re going to have: how we deal with infill and utilizing the space we have available, and not necessarily changing the character of neighborhoods or the downtown area,” Stang said.

Transit-oriented planning must consider all income levels, including those who would depend on transit for daily rides, in lieu of using a vehicle, and those who would choose it for convenience, said Jim DeGrood, deputy director of PAG.

“We need to be serving both needs. If our objective is to get the largest number of people riding transit because of sustainability and air-quality benefits, then we need to look at drawing in discretionary riders,” he said. “But being able to help families live affordably is also something we ought to look at doing with our transit system.”

In Phoenix, Mesa and Tempe, much of the recent affordable housing has developed along the light-rail system, which launched in 2008, said Robinson, of the Drachman Institute.

Private developers get interested when transit options include “fixed guideways” — that is, railways or other infrastructure that’s not easily moved, as opposed to conventional bus routes that can change without adjusting much infrastructure. As developers’ interest piques, land values increase, diminishing prospects for affordable developments, Robinson said.

Local governments should purchase land along anticipated transit routes while it is still cheap, and hang on to it as future sites for affordable housing, she said.

In Phoenix, the nonprofit Raza Development Fund helped build and secure tax credits for 1,000 affordable rental units along the light-rail route, said Silvia Urrutia, director of housing for the fund. She said they were able to acquire the land near the light rail cheaply, in part because private developers initially weren’t interested: They didn’t expect Phoenix residents to give up their cars and use the light rail, she said. But the light rail has been popular, she said.

“They have met 20-year goals within four years,” she said.

Development throughout metro Tucson is inevitable, so smart planning today can help guide that growth, Robinson said.

“This is a real exciting time for Tucson. But this is certainly just the beginning,” she said. “We need to be thinking really clearly and carefully about where we go from here, so that we remember the diversity of our community and so that we provide housing and transportation for the entire community.”