Tucson police no longer use controversial cellphone-tracking devices in investigations and haven’t for more than two years.

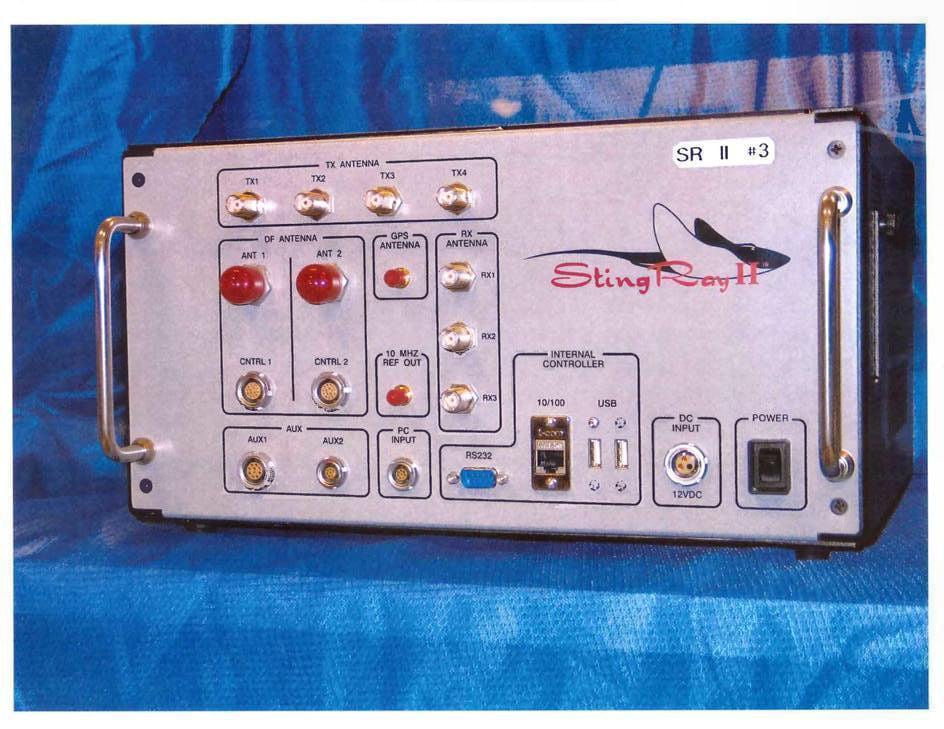

The devices, the subject of a lawsuit filed by the ACLU against the Tucson Police Department, were used in five police investigations since 2010. The city paid $408,000 in federal grant money to Florida-based Harris Corp. for a vehicle-mounted device and a backpack-sized device. That amounts to $81,600 per investigation.

The cell-site simulators mimic cellphone towers and allow police to track the movements of suspects through their cellphones. In an Arizona Court of Appeals hearing last week, the ACLU said the devices raise privacy concerns for people whose phones may be tracked solely because they are in the vicinity of a suspect.

The controversy is not limited to Tucson, where police used the devices without first obtaining a warrant. On Sept. 3, the Department of Justice issued new guidelines for federal authorities requiring warrants for the use of cell-site simulators in all but exigent circumstances.

The last time anyone at TPD remembers using the devices was mid-2013 and the department formally took them out of service in early 2014, said Lisa Judge, principal assistant city attorney and legal adviser for the Police Department.

“It’s been in boxes in a storage closet for quite a long time,” Judge said.

Due to the sparse use of the devices, the city chose not to upgrade them when the time came, she said. The price of the upgrade was “cost-prohibitive in terms of investigative value,” she said.

The city did not replace Stingray with another cell-site simulator and has no plans to do so, Judge said.

TPD is now trying to dispose of the devices, a process that is complicated by rules attached to the federal grant, Judge said. For example, Harris would not be allowed to resell the devices and turn a profit on them twice.

Top TPD officials were unavailable for comment late last week, a department spokesman said.

Although the city is no longer using the devices, the legal battle continues over whether it should release technical and training information about the devices in response to a March 2014 lawsuit filed by freelance reporter Mohamad Ali “Beau” Hodai.

Pima County Superior Court Judge Douglas Metcalf ruled last year that disclosing the information would not be in the best interests of the state.

The ACLU of Arizona, representing Hodai, appealed the decision and Wednesday’s hearing was held to determine whether the city responded promptly and adequately to Hodai’s records request.

The hearing before a three-judge panel also sought to determine whether the best interests of the city outweighed the requirement of the state’s public-records law to disclose records.

The judges also are charged with determining whether the trial court erred in not ordering the city to release communications between TPD and the FBI, saying the request was too broad.

Principal Assistant City Attorney Michael McCrory told the judges that TPD discontinued use of the Stingray devices, which prompted Judge Peter J. Eckerstrom to ask whether the city’s concerns that local criminals would take advantage of any released information about the system were weakened.

One of the five TPD investigations that used Stingray devices is ongoing, McCrory said, and disclosure could jeopardize that investigation and those of other law enforcement agencies across the country.

When the city received the public-records request from Hodai, the FBI expressed concerns about disclosing the information and the city was in no position to disregard those concerns, McCrory said.

The ACLU website says at least 58 law enforcement agencies in 23 states and the District of Columbia use Stingray devices.

The city entered into a nondisclosure agreement with Harris in which the city would allow Harris to challenge records requests in court and would not release any information Harris deemed confidential.

The agreement cited two exemptions to the federal Freedom of Information Act: the protection of business or trade secrets, and information that would interfere with law enforcement proceedings or reveal law enforcement techniques.

At the time the lawsuit was filed, City Attorney Mike Rankin said the city honored the agreement by consulting with Harris about the records request, but did not let the company dictate the city’s response to the request. The agreement includes language allowing the city to comply with the state’s public-records laws.

Court of Appeals Judge Philip G. Espinosa asked whether disclosing information about the devices would allow criminals to develop defensive tactics. ACLU of Arizona lawyer Darrell Hill responded that the city cited no evidence showing disclosure of information has led to such a scenario.

In response to a question from Eckerstrom, Hill said the city could have a legitimate interest in not disclosing information that would affect law enforcement investigations.

However, violating citizens’ Fourth Amendment rights is not a legitimate interest and “the weight of the public interest is very strong” in favor of disclosing the information, Hill said.

The judges will issue a ruling later.