The following column is the opinion and analysis of the writer.

We planned on taking the three-hour train ride to Limoges on Friday evening. From there we’d get on the bus to Saint Just-le-Martel, which is French for “Middle-of-Nowhere.” Until then we had a few days free to explore Paris. On Thursday we wandered across the Seine to the royal chapel of Sainte-Chapelle, stained glass on steroids, which shared an island in the middle of the Seine with the proud husk of Notre Dame and many of the justice departments and courts of Paris. Our sublime reverie inside God’s kaleidoscope was shattered by the screech of sirens just outside the ancient windows and the arrival of gendarmes armed with combat weapons, who evacuated us across the Seine, behind the crime scene tape ringing the island.

A lunatic had stabbed four of his law enforcement coworkers to death next door to Sainte-Chapelle. Paris had gone mad.

Since the Charlie Hebdo madness, every gathering of cartoonists is surrounded by armed security. I admit to being nervous. I had drawn Muhammad once for a cartoon that was widely reprinted. “Better a fatwa than a Pultizer,” joked my Jordanian cartoonist friend, and fellow heathen, Emad Hajjaj. Friday night we sat facing Emad and his lovely wife Lina on the train to Limoges. (I met Emad, a kindred doubter, in Mexico City. He and I became “habibi”: best friends.) On the diner car table between us Lina produced a feast of olives, cheese, sausages, grapes, plastic champagne glasses and a bottle to pop. We talked about our kids, played a fun Jordanian card game and laughed at our good fortune as the French countryside sped past.

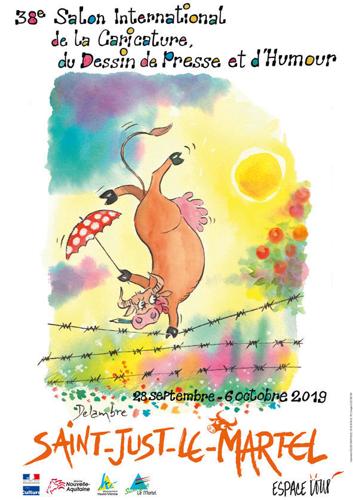

Off the train, hobnobbing with a Bulgarian cartoonist, we boarded the bus to Saint Just-le-Martel, a rural crossroads with no shops, traffic lights, bakeries or cafes; just one charming school and a 12th century stone church overlooking a meadow. The townspeople had transformed their school into the site of an international festival that would attract thousands from all over France. We dumped our luggage in an auditorium where I saw industrious teenagers filling the hundreds of bottles of wine we’d consume over the next two days, fueling our loosened pens and our convivial cheer.

Out of the humble school cafeteria the villagers prepared seven-course feasts, which were served by the same students happy to practice their language skills. Over steak and wine Ellen and I met our host family: Anne-Marie and Claude. Claude, was a local celebrity, a beloved third grade teacher who had taught every man, woman and child in St. Just. And their children. And their children’s children.

After pleasantries, Claude described a recent visit to the cemeteries at Normandy. Thanking me for America’s sacrifice, he feared the world was going mad again. I mentioned a distant relation who was felled by the Nazis that day. I thanked him for his nation holding fast to the revolutionary ideals of liberté, égalité, fraternité through the centuries. We shook hands. I thanked him for Lafayette, for blocking the British navy from reinforcing Cornwallis at Yorktown and for Lady Liberty. And Brigitte Bardot. Long live our democratic republics in a world gone mad. High fives, laughter and more wine.

That morning, we learned it is the habit in St. Just to drink your morning coffee out of a cereal bowl with both hands. And the rooster did indeed crow in French.

I drew for my supper, began sipping wine mid-morning like the natives and had the time of my life.

Returning to Paris we got lost outside a speakeasy and walked across Paris in the rain at three in the morning, got a french lesson from a Ghanaian taxi driver, Merci, and trekked to Montmartre where we found the tree-lined square where artists and caricaturists peddled their work. Steve Sack, of the Minneapolis Star Tribune, suggested we had found our retirement plan.

A French caricaturist made his sales pitch. Steve argued we were both caricaturists ourselves, political cartoonists. In broken French he lamented the crazy times we are living in and insisted on drawing me. “Monsieur, could we … swap?”

“Oui.” I unholstered my pen. A crowd gathered. Markers flying, we drew portraits of each other until “Voila!” We exchanged our sketches. We delighted each other.

I felt sorry for the old artist. He missed his grown son terribly. He had moved to California.

“He left Paris? For California?” The world has gone mad.

Emad likes to feign shock, by saying “Haram!,” it is forbidden, with a spirit of pained regret over losing an opportunity to sin. Our last night in Paris he whispered it in my ear at the Moulin Rouge when the Can-Can girls kicked up their heels. It was the saddest “haram” I ever heard, followed by an elbow from his wife Lina, along with the only cure for a world gone mad: laughter.