Across Cochise County’s Sulphur Springs Valley, the ground sinks more than three times faster today from unregulated agricultural overpumping of groundwater as it did 25 years ago, state records show.

In that valley south of Willcox and west of the Chiricahua Mountains, a stretch of U.S. 191 was recently closed due to a large crack. The ground underneath that part of the highway has fallen 13 inches since 2010.

Four miles away, the ground under a major intersection has fallen 3.5 feet since 2010, and crews have repeatedly repaired a huge earth fissure there. The fissure just reopened a few weeks ago, got repaired, but was again opening this week after heavy rains, neighbors say.

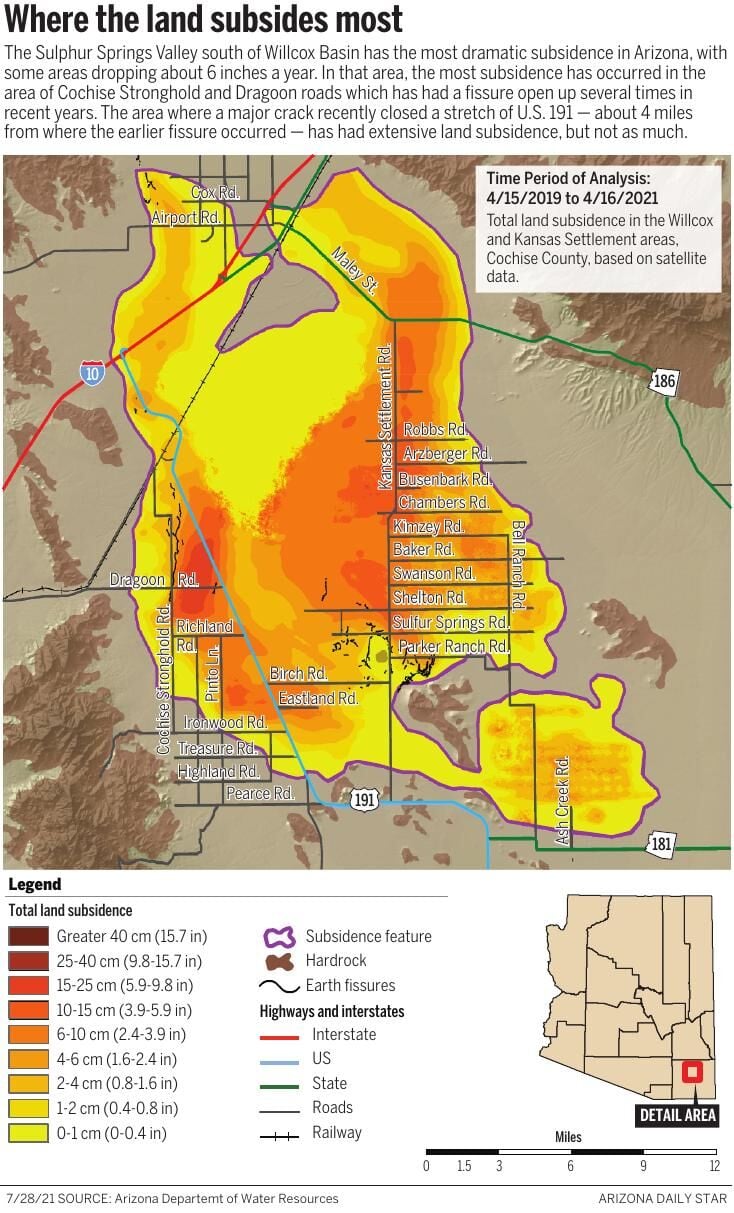

The land collapses in both places are due to a geologic phenomenon known as land subsidence, caused by groundwater overpumping by agriculture, Arizona Department of Water Resources officials have said. The entire Sulphur Springs Valley has the state’s worst subsidence, with some areas sinking 6 inches a year, ADWR hydrologist Brian Conway said.

But, three weeks after the crack closed 191 and two weeks after the repaired highway reopened, officials say it’s unlikely they’ll ever know for sure if this latest crack was caused by subsidence and pumping or was strictly due to natural causes.

The crack on 191 opened up 2 feet wide and up to 10 feet deep in places. But highway crews couldn’t detect the exact depth just by looking at it.

To determine the depth — a key factor in whether the culprit was overpumping — authorities most likely must excavate far beneath the road, said Conway and Arizona Geological Survey and Arizona Department of Transportation officials. That would be expensive and would require closing the highway again.

That’s unlikely to happen, said Bill Harmon, ADOT’s district engineer for Southeast Arizona including Cochise County.

“From the district’s point of view, we just fix what we see, as best we can. I don’t have a budget to do research or anything like that. That might be interesting someday, but it’s not in my wheelhouse,” Harmon said this week.

ADOT closed a 2½-mile stretch of 191 on July 6, after heavy rains caused cracks to open in the road through erosion and forced traffic to detour.

Right after the crack was discovered, Harmon said he thought it was a fissure, caused by subsidence. Large, polygon-shaped cracks on either side of the road are typically caused by natural forces, alternating patterns of dry and wet weather such as Southern Arizona has recently experienced: a record-setting drought followed by near-record monsoon rains.

But the crack on the road itself is “somewhat more linear,” suggesting subsidence as a factor, Harmon said initially.

Geologists from ADOT and the geological survey and an ADWR hydrologist have since examined the area around the crack. It appears to be part of a polygon-shaped network of naturally forming cracks found on either side of the road, they said. These are known as giant desiccation cracks, said Joe Cook, an Arizona Geological Survey geologist.

“Just like the mud cracks you see in a puddle after it dries up, in the same way, cracks form that are usually very narrow, and then when we have a rainstorm, water gets into a crack and it becomes wider and you can see it,” said James Lemmon, an ADOT geologist who spent three days at the crack site. “And this is a naturally occurring process.”

However, an ADWR map showing 10 years of subsidence in the Willcox area shows U.S. 191 passes through several bright red areas indicating the worst known subsidence, near where the recent crack occurred.

Cracks in the pavement running down the middle of the U.S. highway 191 show where a fissure opened near Sunsites.

“So it is definitely possible a fissure could form somewhere along there,” said Cook. “It can be tough to differentiate between the different types of cracks but when a fissure forms through a preexisting desiccation crack network, it can make all the cracks worse — deeper, with more erosion.”

Some of these areas may already have fissures forming, but people don’t know about them until they break the surface, usually on a road or someone’s property, Cook said.

But while farmers have been pumping a mile from where the crack occurred, authorities haven’t observed what’s known as differential subsidence there. That occurs when one area of land sinks more than an adjoining area, and is typically a prime cause of fissures, said Lemmon and Conway.

By contrast, the scientists say the differential subsidence is obvious at the known large fissure running northwest of the 191 crack site. At four miles long and close to 20 feet wide, it has opened up repeatedly over the past two decades at Cochise Stronghold and Dragoon roads, in an area of heavy agricultural pumping.

The intersection lies close to an area of bedrock, and the area east of the bedrock has subsided while the bedrock area hasn’t, Cook said.

“The earth fissure follows that differential subsidence there, extremely well,” ADWR’s Conway said.

Cochise County Highway road crews used to fill it in yearly with aggregate, soil, rocks, concrete slurry and then patching the top with asphalt.

Finally, in October 2017, workers laid a 12-inch concrete slab atop the fissure, said Jackie Watkins, the county’s director of engineering and natural resources.