Paul Hing looks over the yellowed pages of the journal he kept while attending the University of Arizona, smiling as he turns to the entry from April 30, 1986.

“Dad was thrilled about the letter for his 1953 tennis year. He talked about it all weekend,” the entry reads.

Paul Hing remembers that day well. His father, Holy Hing, excitedly told him how for the first time ever, he’d be able to attend the UA’s annual letterman’s breakfast — an event reserved solely for athletes who had been awarded a varsity letter.

Hing was 56 at the time, decades removed from his time as a member of the Wildcats’ tennis team, but he had never before been permitted to attend any letterman events.

That’s because his varsity letter came late — 32 years after he graduated, to be precise. The delay did not matter one bit to Holy Hing, a die-hard Wildcats fan.

His children believe the letter, a 12-inch by 12-inch swath of crimson cloth cut into the shape of a familiar “block A,” was his greatest honor.

Holy Hing treasured it up until his death on June 3 at the age of 90.

‘He loved the competition’

Holy Ong Hing lived most of his life in Coolidge. Despite his proximity to both Tempe and Tucson, there was never a choice when it came to picking a college. Hing bled red and blue from the very start.

“It seemed like the boys always knew they wanted to go to UA,” said Tod Hing, the second of Holy Hing’s four children. “The girls favored ASU, with four of his sisters going to ASU.”

Holy Hing and his nine siblings all attended college, which was unheard of at that time.

Hing began playing tennis while attending Superior High School and was mostly self-taught. His children say that he wasn’t very good at first, but worked hard to improve his game.

“He had a short motion on his serve, kind of pokey-looking, but accurate. Flat. And his strokes were also rather short, flat, and controlled rather than hard. I don’t remember playing him, but I remember him quite well,” said Allen Fox, who won NCAA doubles and singles titles for UCLA in 1960 and 1961.

Fox got his start in tennis in Tucson when he was 14, playing for Tucson High before moving to Beverly Hills when he was a junior.

He went on to be a Southern California junior champion, was ranked No. 4 in the country in 1962 and was in the top 10 in the U.S. five times between 1961 and 1968.

“I’m sure he would have beaten me,” Fox added. “I was lucky that he was nice enough to practice with me.”

Hing did beat Fox, as he told his children multiple times, but added that Fox didn't get good until later. Hing's game also improved: He became good enough to join the UA’s tennis team in 1952.

It’s believed that he is the first Asian American to play on the Wildcats’ tennis team, and one of the few Asian Americans to play varsity sports at the UA at the time.

“He loved the competition. He loved that a short guy can compete with anyone — any height, any weight, any size. He loved the parity of that,” said Paul Hing, Holy’s son and a California tennis pro. “And of course, he loved winning.”

Holy Hing’s four children all followed in his footsteps, taking up tennis and attending the University of Arizona. Three of Hing’s children still play tennis recreationally and his oldest son works as a tennis pro in Southern California.

Hing earned a nickname — “The Human Backboard” — for his ability to return just about every shot. It was a great equalizer, a way to beat taller, stronger opponents.

Said Tod Hing: “He let the other person make the mistakes.”

And while Hing went undefeated against ASU during his time at the UA, worked his way up to at least the No. 6 position on the varsity team and was pictured in the tennis team’s yearbook photos from 1952 and 1953, he was not awarded a varsity letter.

Rather, he moved on into adulthood.

After graduating from the UA in 1954, Hing went to work in his family’s grocery store for a few years before putting his education degree to use and becoming a teacher.

Hing spent four years teaching at Picacho Elementary School before returning to Coolidge in 1961 to take over his father’s store, Save Money Market, which he would run for the next 43 years.

“That was the thing about our dad,” Glenn Hing said. “He did it, but then he moved on to the next thing, whatever was the next phase of his life.”

'It could have been political at the time'

Holy Hing’s parents were very traditional, and when he wasn’t married by the age of 32, they took a page from their ancestors’ playbook.

“They’d take you back home to Hong Kong to find a wife,” Tod Hing said. “There’s a matchmaker there that would set up these meetings with probably a girl every day.”

Hing met a different woman every day for a month before he met Lola. They fell in love and were together until Lola Hing’s death in 2008.

The couple was married in Hong Kong and returned to Coolidge, where Lola experienced the culture shock of her life. The town of 7,000 people had just three Asian American families.

Then there was the weather.

“She came over to the U.S. and Arizona, not knowing it was going to be 120 degrees and not speaking a single word of English,” Tod Hing said.

Glenn Hing, left, and Lisa Hing talk with their brother Tod Hing, right, outside his house in July in San Francisco. Their father, Holy Hing, graduated from the University of Arizona in 1954 and was on the Wildcats’ varsity tennis team — possibly as one of the first Asian Americans to play on the UA varsity tennis team.

A few years after their return to the States, Paul was born. Tod came a short time later, and Glenn and Lisa weren’t far behind.

“She grew to love the small town and open space, coming from Hong Kong. She loved the backyard and the pigeon coop,” Paul Hing said. “She was the disciplinarian of the family, making sure we did our homework.”

With Lola Hing in charge of academics and obedience, Holy Hing jumped at the chance to pass along his love of tennis to his clan.

“It wasn’t like he pushed us or anything; we all wanted to practice and play,” Paul Hing said. “That has stuck with us, stuck with me as a tennis pro teaching now. Everything starts with fun, then you spoon-feed in the technique along with the fun.”

The Hing kids took to the game quickly, all playing at Coolidge High School. Over the course of a decade, they dominated the state’s tennis championships, winning a collective eight singles titles among them.

Paul Hing won championships in 1980 and 1981; Tod Hing one-upped him, winning in 1982, 1983 and 1984.

Then it was Glenn Hing’s turn, and he claimed victory in 1985 and 1986. Lisa, Holy Hing’s only daughter, won her own state title in 1990.

The “Hing Dynasty” was born.

All four Hing siblings then attended the UA, earning degrees from the school.

And while there was no doubt that Holy Hing was happy with his life, and proud of his children, he often thought back to his college days. Maybe it was watching his children play tennis, or witnessing them graduate from his alma mater. He began to wonder — often — why he was denied a varsity letter.

“Who knows (why)? It could have been discrepancy between him and the coach. It could have been political at the time,” Paul Hing said. “But he complained about it every year for 32 years to all of us ad nauseam.”

'A fierce, determined competitor'

By the start of his senior year at the UA in 1985, Paul Hing was ready to take action.

He approached assistant athletic director Bob Bockrath and asked what it would take to get his father the letter. Bockrath suggested that some of Holy Hing’s former teammates write letters on his behalf.

And so began a months-long effort to find men scattered across the country, a task that was much more difficult before the advent of the Internet.

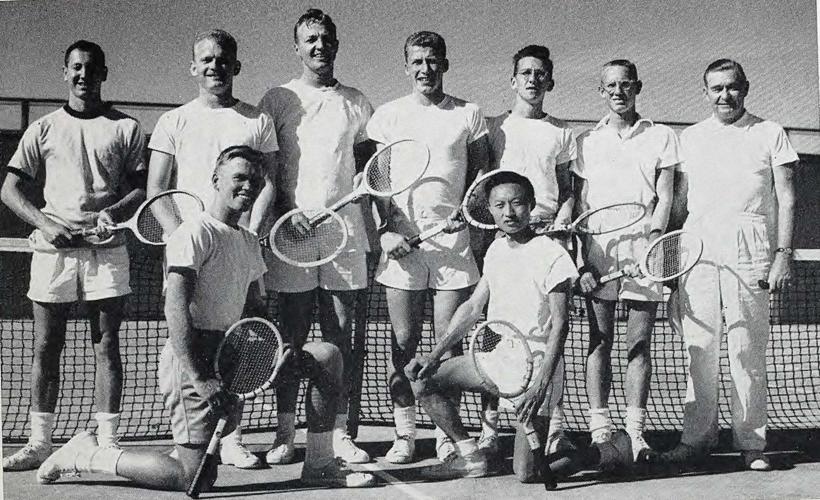

Holy Hing, bottom right, pictured with the 1952 University of Arizona tennis team. Hing’s teammates helped him get a letter three decades later by writing letters to the UA, saying he was a fierce, determined player who was also a gentlemen.

Before long, the team’s best players were sending letters advocating for their former teammate.

“I vividly recall Holy Hing as a fierce, determined competitor. What he lacked in size, he more than made up for with his ability to cover the court and his never-say-die spirit,” former teammate Philip Malinsky wrote.

“And, although it does not seem to make a difference with today’s players, he was always a gentleman on the court.”

Added Bill Crary: “Awarding a varsity letter now might imply an injustice was actually done at a time past. (However) not awarding a varsity letter might continue an injustice that has apparently had a long and persistent effect.”

The athletic department agreed, and on April 23, 1986, Paul Hing received word that his father would receive a letter for the 1953 tennis season.

Paul picked the “A” up from McKale Center and, together with his siblings, presented it to their father.

“It was perhaps the greatest honor for him during his lifetime,” Tod Hing said.

'You’re contributing to the team’s success'

It’s unclear why Holy Hing didn’t get his letter the first time, but there are a few theories, and no one is disputing the fact that he earned it.

Coaches at the time decided who received varsity letters. It wasn’t uncommon for athletes to play on varsity teams and not be awarded a letter.

“In the early days of athletics … coaches felt very strongly that varsity ‘A’ wasn’t a participation award, but rather it was something you earned,” said Kathleen “Rocky” LaRose, who spent 34 years at the UA, rising to Deputy Director of Athletics, before retiring in 2013. “Because of that, our coaches clear up until the modern day of athletics had some pretty stringent policies on how you earned an ‘A.’ ”

Through the early 1980s, LaRose said, coaches submitted criteria for receiving a letter to the department for approval.

“Later on, as we evolved, everyone realized now that if you’re on a team, whether you’re a starter or a third-stringer, you’re contributing to the team’s success,” LaRose said. “We’re one of the Power 5. We are elite athletics, and the philosophy of the athletics department is the pursuit of excellence.”

Holy Hing’s Arizona Wildcats stadium chair is seen next to his tennis trophies where he lived with his son in San Francisco. Hing was finally awarded a letter in 1986.

When the mindset shifted, the department began to award retroactive letters to those who could provide records and research to make their cases.

While LaRose said the department tries not to overrule coaching decisions, when it comes to a situation like Hing’s, “You have to do the right thing.”

'I think we should be idolizing him'

Hing’s children believed he helped pave the way for many other Asian American athletes at the UA.

“People always asked if he faced discrimination. If he did, it didn’t stop him from doing what he wanted to do,” Tod Hing said. “He didn’t use it as a crutch and he didn’t play the victim. That was part of his life and he dealt with it. Deal with what you have control of — that’s what he taught us.”

Hing retired from the Save Money Market in 2004 at the age of 74, but he kept busy. He sang and danced. He learned to play mahjong following Lola’s death, and soon was teaching it at a senior center.

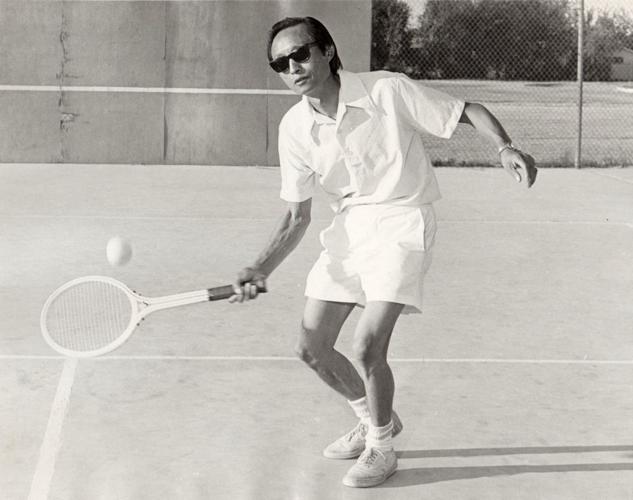

Paul Hing, a former UA student, tennis player and Holy Hing’s oldest son, passes on his father’s legacy and love for the game, working as a tennis pro in Southern California.

Hing relocated to Northern California to be closer to Tod, Glenn and Lisa. There, he enjoyed playing table tennis, cards and table shuffleboard.

“He was the Michael Jordan of shuffleboard,” Tod Hing said.

Hing’s heart remained in Arizona though, and he would visit Coolidge at least three times a year, stopping by his old haunts and checking in on his friends.

He kept an even closer eye on the Wildcats. Hing wore UA gear everywhere he went, in Arizona and California, and took pride in wearing cardinal and navy on special occasions.

When his family took professional portraits, they asked him to not wear his UA clothes.

“Why?” he’d ask.

Eventually, Hing’s children gave up that battle.

Holy Hing was a lifelong University of Arizona fan, having graduated from the school in 1954. His children said it was nearly impossible to get him to leave his UA hat behind on formal occasions.

“He loved the UA. He idolized and followed all of the athletes at the UA for every sport,” Tod Hing said. “My dad loved amazing athletes and I want him to get recognized as an amazing athlete as well. What he went through to make it to the varsity team, and then to wait 32 years to get his varsity letter, I think we should be idolizing him.”

Like any die-hard UA fan, Hing also cheered on Wildcats when they moved onto the pros, one of his favorites being Steve Kerr.

“I remember planning my wedding and making sure that it didn’t fall on a playoff game,” Lisa Hing said.

And even after moving away, Hing continued to claim Arizona’s professional teams as his own.

But perhaps greater than his UA fandom was Hing’s allegiance to his grandchildren’s various sports teams. Last year, Hing was taken to the emergency room shortly before one of his granddaughter’s basketball playoff games. As the clock ticked down to tipoff, Hing got impatient.

“He pulled his IV out and hailed a cab to get to the game,” Tod Hing said. “My daughter was warming up, saw him walking across the court asked if he was supposed to be there.”

Hing’s children said he lived life to its fullest, touching countless lives and doling out lessons along the way.

When Paul Hing was 10 years old, he won the Coolidge Examiner’s college football pick ’em contest twice.

His secret? Paul listened to his father’s advice.

“’Don’t do what everyone else is doing, be different.’ He kind of ingrained that in all of us,” Paul Hing said. “That embodied our dad.”