OROVILLE, Calif. — If you look close enough, you can see the slight elevation in the corner of Jerry Johnson’s backyard. That’s where the pitcher’s mound used to be.

If you imagine hard enough, you can picture the entire setup. The batting cage. The old-school video camera. The JUGS machine. The basketball court. The lights. The kids playing at all hours.

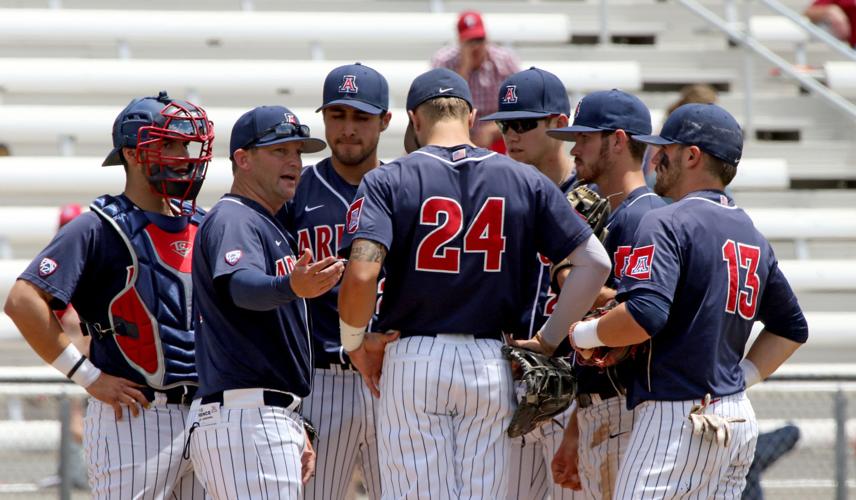

This is where it all started for Arizona baseball coach Jay Johnson — where the groundwork was laid for the painstaking approach that helped the underdog Wildcats advance to the brink of the College World Series title in Johnson’s first season on the job.

He spent every waking moment taking batting practice, shooting free throws or breaking down tape at his parents’ modest three-bedroom home in the Thermalito neighborhood on the west side of Oroville.

Once known for its gold mining, and recently in the news when its nearby reservoir nearly overflowed, Oroville is a small town (pop: 19,000) with a big heart. It’s a blue-collar city nestled in the middle of Northern California farmland, “a town of high work ethic — elite work ethic,” Johnson, 39, says.

“The foundation of who I am is from growing up there,” he says, “and it has served me well at each stop after that.”

From San Diego to Reno to Tucson, Johnson always brought a little piece of Oroville with him. If you want to know how Johnson got the Wildcats to maximize their potential last season — and has them ranked in the top 15 entering the Pac-12 home opener against USC on Friday — look no further than this place.

“Limited resources and grit,” says Bob Schmautz, one of Johnson’s former high school coaches, when asked to describe Oroville.

The same could be said of Johnson in his playing days, or of the 2016 Arizona squad that went from preseason No. 9 in the conference to national runner-up.

They’re all proud overachievers.

His father’s son

Jerry Johnson greets a visitor in front of his immaculately manicured, one-story house, on a partly sunny Friday morning. He is decked out in University of Arizona gear — camouflage baseball cap and navy T-shirt atop tan Dickies and brown work boots — which he insists is just a coincidence; his closet is full of Wildcats paraphernalia.

The garage door is open, revealing a neatly displayed wall of tools to the left. Jay Johnson’s father is busy doing yardwork, cleaning up after another day of heavy rain that damaged Oroville’s spillway and threatened to flood the region.

Thousands would be evacuated before being allowed to return to their homes, and the potential worst-case scenario was averted.

Jerry takes a break to talk about the older of his two sons: how Jay acted as a kid, how he carries himself now and how little difference there is between the two.

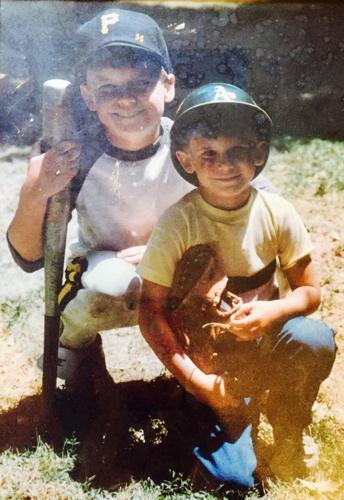

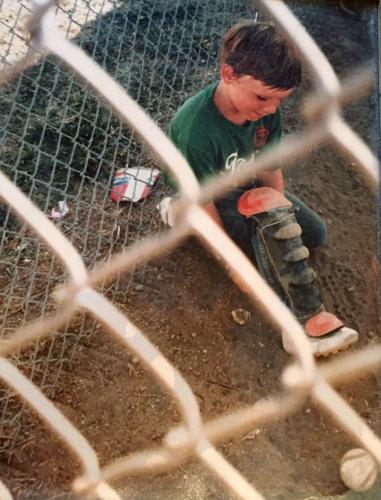

“He wasn’t normal,” Jerry says while sipping coffee at a small breakfast table, where he has laid out photos of Jay as a youth. In one, he is strapping on catcher’s shin guards over jeans in his first year of T-ball; in another, he is wearing a Pittsburgh Pirates cap and squatting beside younger brother Jimmy, cradling a worn-down silver bat in his right hand.

“He did not do the normal things teenagers do,” Jerry continues. “If raising kids was this easy, I would have had 10 of them.”

Jerry and Jay were, and still are, kindred spirits. Jerry was a wildly successful boys track coach at Oroville High School. The Tigers went undefeated in varsity dual meets from March 3, 1984, to March 23, 1989, often beating schools with larger enrollments.

“Jerry was one of the best track coaches in California,” says Tom Frazier, a longtime family friend and the current athletic director at Oroville High. “For 10 years, they were untouchable.”

A plaque commemorating Jerry’s achievements — “Team of the ’80s” — rests on a mantle in the trophy room adjacent to the kitchen. The room, an addition built by Jerry and his father, represents one of the few areas where Jerry and Jay differ. Jerry’s hunting prizes are mounted on the walls, including four deer heads, a bear head and full-bodied wild turkey.

“On Thanksgiving, Jerry and Jimmy would go pheasant hunting,” Jay’s mother, Beverly Cowden, says later that day. “Jay would watch the Cowboys.”

Schmautz, also a family friend, remembers visiting the Johnsons one time. While Jimmy was working outside, Jay sat for hours in front of an “old tube TV” watching baseball instructional videos. One of his favorites: “Teaching Kids Baseball with Jerry Kindall,” starring the legendary coach at Arizona.

“What kid does that?” Schmautz wonders.

A kid who is his father’s son.

“He’s a detail guy,” says Frazier, who played youth baseball with Jay. “He learned that from his dad. He was meticulous.”

‘Born to do it’

To understand Jay Johnson’s borderline obsession with college baseball — or, more specifically, his borderline obsession with preparing to win college baseball games — it’s instructive to talk track with his father.

“I scouted more than any track coach in the country,” Jerry Johnson says. “I knew every kid.”

Jerry would film opponents’ meets, looking for any edge, no matter how minuscule. He would study the relay teams. Maybe, if he configured his in a particular way, he could put pressure on an opposing runner and force a bad baton exchange.

“The preparation part — that’s what you can control,” Jerry says. “You can’t control the outcome of a game.”

Winning those dual meets, which featured 16 events, required fitting multiple puzzle pieces together. It required a detailed plan, not unlike assembling a college baseball team. You get only 11.7 scholarships for 27 players.

Jay relishes that annual challenge. Those who know him best insist he was meant to follow his dad’s path into coaching.

“He was born to do it,” Jimmy says. “He was driven to do it.”

Jerry swears that Jay first expressed interest in becoming a college baseball coach when he was 5 years old.

When he was in middle school, he would tag along with his father to coaching clinics and conferences.

Hearing Lou Holtz and Tom Osborne — two of the most successful college football coaches of all time — discuss their philosophies opened Jay’s mind to myriad possibilities. When you come from a small town, he says, it’s easy to feel as if you can’t go beyond the city limits, as if you can’t see past the outfield wall of the local Little League park.

“Being exposed to those kinds of things,” Jay says, “helped me see outside of that and not build a fence around what I could accomplish.”

The words of Holtz and Osborne “mesmerized” young Jay, Beverly says. At one point, he made a request of her: “Mom, I want to turn my desk around.” He rearranged the furniture so that his desk faced the door, turning his bedroom into a coach’s office.

A beautiful mind

Jay Johnson had big aspirations all right.

“I thought I was going to win the Heisman Trophy,” he says.

Before he began his coaching career at Point Loma Nazarene, where he played baseball for the Sea Lions, Jay was a multisport standout at Oroville High. Small-town kids, at least back then, didn’t specialize. Jay played tailback in the fall, point guard in the winter and middle infield in the spring.

He made every effort to get the most out of his 5-foot-7-inch, 146-pound frame.

“He had amazing fundamentals,” says Frazier, who often served as Jay’s double-play partner. “He knew the game. It didn’t matter what sport we were playing.”

“He was limited athletically. Probably average,” says Schmautz, who coached Jay when he was a sophomore in high school. “He figured out how to make himself and everybody around him better.”

In football, Jay had help from his father, who was the Tigers’ offensive coordinator. Jay was undersized, but quick and smart. So Jerry would deploy him on the wing or in the slot and figure out ways to get him the ball in space.

Father and son would spend “hours and hours and hours” studying film together, Jerry says. “You could line him up anywhere, and he could run any route.”

Jay rushed for more than 1,000 yards as a senior, averaging 9.2 yards per carry. He had the unique ability, Schmautz says, to tabulate his yardage as he accumulated it.

It wasn’t an act of vanity but a product of Jay’s competitive nature — and an example of his beautiful mind when it came to the details of team sports.

Another man who knows Jay, Oroville High varsity basketball and freshman football coach Rob Anderson, describes him as “the guy who knew what to do and when to do it.”

Jay would parlay his sound fundamentals and high athletic IQ into a baseball playing career at Shasta College in Redding, California, and Point Loma Nazarene in San Diego, where he batted .326 as a senior second baseman.

Here, the line can be drawn from Oroville to Tucson, from Jay the player to Jay the coach, from one overachiever to another.

Beverly, a longtime human-resources manager, puts it like this: “He’s not afraid to take someone who may not be perfect and help them grow.”

In that regard, the 2016 Wildcats might have been the embodiment of their first-year coach. They were overlooked and underestimated, picked by Pac-12 coaches to finish ninth out of 11 league teams.

Their core consisted of four seniors — Ryan Aguilar, Nathan Bannister, Zach Gibbons and Cody Ramer — who played by far the best baseball of their careers under Johnson and his staff.

Asked about his brother overcoming expectations, Jimmy says: “There’s nothing more gratifying than that. That’s a small-town thing.”

Never satisfied

The rain rarely subsides on a cool Thursday afternoon as Frazier shuttles a visitor around town — from the Souper Subs sandwich shop on Oroville Dam Boulevard to Oroville High with its “Hoosiers”-esque gyms and purple accents to the muddy diamonds where he and Jay played Little League baseball for their fathers.

One stop, about three-quarters of a mile southwest of downtown, is particularly noteworthy: Harrison Stadium, where all the big football games, track meets and graduation ceremonies take place.

About 10 years ago, voters approved a bond measure for $12 million in renovations for the stadium. Frazier, who frequently must raise funds and enthusiasm for facility upgrades as Oroville High’s AD, considers that decision emblematic of his hometown’s community spirit.

Neither Jerry nor Beverly is from here — he was born in Nebraska, she in Alabama — but something drew them to this town besides Jerry getting a job at Oroville High 44 years ago.

Oroville, located about an hour north of Sacramento, is the county seat of Butte County but is considerably smaller than neighboring Chico (pop: 92,000). The citizens and athletic squads of Oroville constantly are trying to prove themselves. They do so by rolling up their sleeves. “People aren’t afraid to work on a Saturday,” Frazier says.

Jerry stopped coaching in 2002 and stopped teaching in ’09. He just turned 68. But he continues to work as a part-time instructor for the family business, E-Z Way Driving School.

Beverly oversees about 150 employees at RCBS, which manufactures ammunition reloading equipment.

“Why do you work?” Jimmy will ask her from time to time.

“She’s never not busy,” he says. “Jay’s the same way. It’s the same thing with my dad.”

And with Jimmy, who helped to design and build his own house, a ranch on the outskirts of town, and runs his own construction company, Johnson Engineering.

It was no surprise, then, that Jay was “pretty much in the war room the whole time” the Wildcats were in Omaha last June, Jerry says. Except this one time when Jerry bumped into Jay around midnight in the hallway of the team hotel.

“What are you doing?” Jerry inquired.

Jay wasn’t quite comfortable with his knowledge of Arizona’s next opponent. He had more scouting reports to read, more video to watch.