If Lute Olson’s Hall of Fame basketball coaching career could be measured from the floor up — in part by a weak moment somewhere, somehow — even that only winds up exposing a strength.

Try March 13, 1997, for example. Olson’s Wildcats were trailing 13th-seeded South Alabama by 10 points with 7:31 left in their first round NCAA Tournament game.

Already in the 1990s, Arizona had lost first-round games to East Tennessee State, Santa Clara and Miami (Ohio), and then UA-associate head coach Jim Rosborough once said an “awful” feeling pervaded the bench as the second half progressed.

Had Olson’s famously even-keeled approach to all games not given the Wildcats an extra boost of fire for a stealthily dangerous opponent? Had Arizona players been lulled to sleep by the Jaguars’ slow-down offense? Were the Wildcats wilting under immense pressure, not on the court but in their heads?

Maybe, maybe not. Ultimately, it didn’t matter.

“Two things,” said Georgia Tech coach Josh Pastner, a walk-on guard for the Wildcats in 1997. “We won the game. And Coach Olson is in the Hall of Fame.”

They won the game because Olson, in another of his top coaching strategies, had made a point of recruiting tough, resilient players with a winning pedigree — guys who didn’t take losing for an answer.

And so it was that guard Miles Simon, whom Olson pulled out of Southern California powerhouse Mater Dei High School, shook off some early-game struggles and ignited a 17-0 run with a pair of free throws and a baseline jumper to help the Wildcats eventually beat South Alabama by eight.

Then Olson’s steady, this-is-just-another-game approach flipped into an overwhelmingly positive attribute, helping the fourth-seeded Wildcats to confidently mow down three No. 1 seeds en route to the national championship, with an overtime Elite Eight win over 10th-seeded Providence tossed in along the way.

The feat is considered the crowning moment of Olson’s 24-year Arizona career, but he had arguably many better teams. Each of his three other Final Four teams at UA — in 1988, 1994 and 2001 — all were among college basketball’s best, while the 2002-03 Wildcats carried a No. 1 ranking throughout most of the season before losing by three points to Kansas in the Elite Eight.

“Don’t let the tournament define teams,” said Matt Muehlebach, a Pac-12 Networks analyst who played for Olson’s teams in the late 1980s and early 1990s. “Sometimes it’s unfair. The team in 1992-93 was unbelievable. They were 24-4, they were 17-1 in the Pac-10. They had (Khalid) Reeves as a junior. (Chris) Mills as a senior. (Damon) Stoudamire as a sophomore. They were stacked to the gills.

“And then they lost to Santa Clara. I don’t think that defined what that team was. That’s the same backcourt that went to the Final Four the next year.”

Game over game, season over season, the Wildcats were always a contender. Over 24 seasons, Olson won or shared 11 Pac-10 titles and made 22 NCAA Tournament appearances. If a 1999 first-round game had not been vacated because of NCAA sanctions, Olson would have been credited for 23 straight appearances, the fourth-longest streak of all time.

That’s a remarkable string of consistent success, and Olson did it by being consistent in all areas: the way he evaluated recruits, the way he drilled them in practices, the way he gave them freedom in games and in the way he adapted.

Here’s a closer look at how he did it.

Fit

Cholla High School grad Sean Elliott turned out to be the perfect player to help Lute Olson turn the program around.

Back when he was a lightly-used freshman “Gumby” — the early term for Olson’s enthusiastic bench-warmers — Muehlebach didn’t yet have college statistics or accomplishments for Olson to brag about at booster or fan or team functions. So instead, Olson introduced Muehlebach within a lens he could appreciate.

“All he would say is, ‘You know, he was in California and his team lost in the state championship by one. Then he went to Kansas City as a senior and his team won the state championship.’” Muehlebach said. “That was all he would talk about.”

Olson wanted winners, guys who simply weren’t conditioned to lose, and guys who knew how to make sure they didn’t. That didn’t mean just having talent, but also mental toughness and smarts.

“Whether you were a McDonald’s All-American or not, everybody who played for him had a (high basketball) IQ,” said Pacific coach Damon Stoudamire, who led the UA to the 1994 Final Four.

In the most famous example of his recruiting evaluation skill, Olson couldn’t help but notice a slender and not particularly quick guard who didn’t hold a single Division I scholarship offer even after he graduated from high school.

That player’s name, of course, was Steve Kerr.

“Lute,” Olson’s wife, Bobbi, reportedly said, “Please tell me you’re kidding.”

He wasn’t. The kid could shoot, a singularly excellent skill Olson wanted, and there was a toughness, an intelligence about him that he also noticed. A nice guy off the court, Kerr played with ferocity and savvy on it.

So Olson offered Kerr a scholarship. Kerr came to Tucson, set the (still-standing) NCAA record for 3-point shooting percentage (57.3) in 1987-88 and helped lead the Wildcats to their first Final Four. His No. 25 jersey now hangs on the wall inside McKale Center.

“What (Olson) evaluated more than anything was the intangibles,” Muehlebach said. “He got guys who were really smart. He got guys who were really competitive, really hard-nosed. They were winners.

“Think of all the guys that just played for him and their competitive nature — Damon Stoudamire, Steve Kerr, Richard Jefferson, Andre Iguodala — incredibly competitive, but very smart. Loren Woods was one of the brightest players he ever had. And Jason Gardner was like the consummate Lute recruit: Smart, tough, hard-nosed, a winner. That was it.”

Gardner was the 1999 Indiana Mr. Basketball while leading Indianapolis’ North Central High School to a state title, but the Wildcats almost muffed a potential recruiting break.

Gardner was a high school sophomore when the Wildcats held a practice in the school’s gym before playing in the 1997 Final Four in downtown Indianapolis … and they didn’t let him in.

“It’s kind of weird how it all came full circle,” said Gardner, now the head coach at North Central. “I remember being a kid trying to come in and watch (Arizona) practice, and all the doors are locked and closed. But two years later, I’m the starting point guard at Arizona.”

Fundamentals

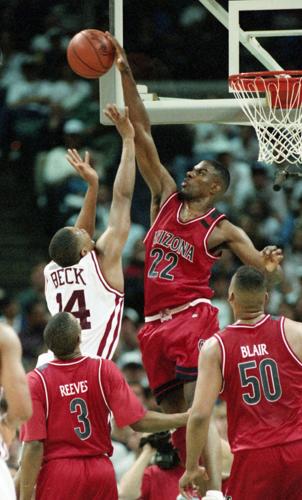

Ray Owes (22) and the Wildcats shook off two straight first-round losses by advancing to the 1994 Final Four.

Once Olson pulled all that talent and all those intangibles together, he didn’t waste a second molding them.

Olson was famous for drilling the same fundamentals, over and over and over, with precision, building a sound foundation with which his teams used to improvise in games.

Everyone knew where to go, how to get there and what to do, wherever the ball bounced.

He “was the best fundamental coach I’ve ever been around,” said UA associate head coach Jack Murphy, a manager and aide for Olson’s UA teams in the early 2000s. “He worked on ballhandling, passing, shooting, the basics of the game every day and he was meticulous with how he coached, how he wanted guys to do it.”

Without prompting, former UA guard John Ash used the exact same adjective to describe Olson’s practice style. Twice, in fact.

“Coach Olson was meticulous about spacing, about execution — and when I say meticulous, I’m talking about inches, on every sport on the court,” said Ash, a Tucson native who now sells commercial real estate for CBRE. “In terms of spacing, how you play the game, and the fundamentals, he was a tactician to the nth degree.”

The fundamental drills weren’t just something the Wildcats did in the preseason, either. Olson made it a season-long habit.

Jawann McClellan, a Houston police officer who played for Olson’s final three UA teams, said the Wildcats would typically spend only 20-45 minutes preparing for their next opponent in any given practice and the rest on themselves.

For four-year players in particular, all that might have seemed overwhelmingly repetitive. But Stoudamire said it never bothered him.

Not when he kept seeing the sort of results that propelled him into being a 1995 All-American and the 1996 NBA Rookie of the Year.

“Every single day, the same thing,” Stoudamire said. “The first 30 to 45 minutes of each practice was the same thing. I never rolled my eyes at it. I did it every day because it made me better.”

Players’ technique was constantly under review, too. Even when the team split up in positional drills, during which Olson allowed his assistants to do the primary instruction.

“He was incredible in practice because he could be at one end of the floor and see the opposite end,” Murphy said.

“With his loud booming voice, he’d correct a player or congratulate a player, and you didn’t know he was watching. He always had command of practice.”

Freedom

Jason Gardner, right, was the perfect guard for Lute Olson: smart, hard-nosed, tough and eager to play at a fast pace. Gardner helped UA to the 2001 title game.

All those practice drills might have made October tedious, but games were another story. Olson took his foot off the gas, trusting his talent to make the right decisions on the fly, knowing that they had good reactions to anything practically drilled into their subconscious.

“What was so great about it was that when you got to game time, he was as far from a micromanager as I’ve ever seen,” Ash said. “He wanted you to execute based upon what you’ve been taught. These things were taught every year from start to finish. The system was not complicated. Definitely not.”

The system may have been no more simple than in the Wildcats’ 1993-94 Final Four season, when Stoudamire and Khalid Reeves engineered a stunningly electric and efficient backcourt.

Olson let them go.

“He did all his coaching in practice,” Stoudamire said. “When you think about Arizona teams, man, we weren’t diagramming plays. We weren’t doing that. I mean, I’m hard-pressed to think of a time we came out of a timeout and he diagrammed a play.

“We had about two plays and we played off each other. That’s all we did.”

By the time McClellan played for the Wildcats, he said they had quite a few more plays than that.

In theory, anyway.

“We probably had like 30-some, 40 plays, but we never ran ’em,” McClellan said, chuckling. “He was more of a mismatch type of coach and he didn’t hold anybody back. He knew if you had a mismatch (to exploit) he would let you go to work. His biggest thing was ‘Take him, take him.’

“He developed you. We had a lot of individual stuff that we would do in practice, but once we got into games, he let your individual talents go.”

Flexibility

Arizona’s Mike Bibby (10) goes up against Kentucky’s Jared Prickett, rear, and Nazr Mohammed (13) during the first half of the championship game at the NCAA Final Four Monday, March 31, 1997, in Indianapolis.

Over a Hall of Fame career that also included coaching USA Basketball to a surprise 1986 World Championship and Iowa to the 1980 Final Four, Olson received credit for staying ahead of the curve and tweaking his system to fit the talent he recruited.

When he had three 6-foot-10-inch-plus bigs in the early 1990s — Brian Williams, Sean Rooks and Ed Stokes — Olson ran with what was called the “Tucson Skyline.” He shifted the offense heavily to the backcourt when Stoudamire and Reeves emerged a few years later. With those two guards combining for 42.5 points per game, the Wildcats averaged 89.3 and reached the Final Four in 1994.

“We were the guinea pigs,” Stoudamire said. “In ’93-94, he changed his whole style. And, by the way, you’ve got a head coach (who already) went to two Final Fours, and he changed his whole style? For him to do that is amazing.”

Then, in 1996-97, Stoudamire said Olson “took it to a whole ’nother level” with a three-guard offense featuring Mike Bibby, Miles Simon and Mike Dickerson, and complemented by a few slender, athletic big men plus energetic bruiser Gene Edgerson.

“That ’97 team, we did not have size, we didn’t have height, we didn’t have strength, but we did have basketball IQ, high levels of athleticism and just the willingness to leave everything on the floor,” said Bennett Davison, the Wildcats’ bouncy power forward from 1997. “Me, A.J. (Bramlett) and Donnell (Harris) might have been the skinniest lineup in NCAA history.

“I think he changed the game to where you don’t need a true big guy. Basketball is about guard play, and even big guys can be inside guards.”

Still, Olson didn’t stop changing there. Not long after Stoudamire and Mike Bibby came Gardner and eventually Mustafa Shakur in what became known as “Point Guard U.” But Olson also still ran plenty through cerebral 7-footer Loren Woods in the early 2000s, while the UA became something of “Small Forward U” at the end of his career thanks to guys such as Jefferson, Luke Walton, Hassan Adams, Iguodala, McClellan and Chase Budinger.

“He kept adjusting and adapting,” Pastner said. “That’s what made him so special. He won in the ’70s, the ’80s, the ’90s and the 2000s. He wasn’t just staying put.”

Yet the core of Olson’s coaching never changed. He still valued motion offense no matter what his roster looked like, always running a system that routed the best shots as much as possible to the best players, whoever and wherever those players were.

And they moved, always. Even the “Tucson Skyline” team of 1990-91 still averaged 86.3 points a game.

“All of Lute’s teams wanted to get up and go,” Muehlebach said. “There may have been a tweak or two, but Lute’s mainstays were three (players) outside and two in the post. It was just simple. A guard would get the ball, pass to another guard and you try to penetrate and break your man down.

“Or if you don’t penetrate, you throw it inside and that guy can hit (shots) or you throw it inside and you cut. We would have always a big man flash to the elbow (for catching a pass) and you create the high-low. But it was always very free-flowing.”

Leading up to a game, Olson never changed his demeanor, either. He prepared the same way every game.

“He didn’t believe in rah-rah speeches,” Pastner said. “He believed in preparing the same way for Marathon Oil (a frequent exhibition opponent) as you would for UCLA or Stanford. Didn’t matter.”

Over his 24 seasons at Arizona, that worked out pretty well far more often than not. The Wildcats won over three-quarters of the time. They won 57% of their games against ranked teams. And Olson won more Pac-10 games (327) than anyone, even John Wooden (304).

Sometimes his guys were small. Sometimes they were big. Sometimes their strength was in driving to the basket. Sometimes in shooting. Sometimes with dominant inside play.

But whatever they were, under Lute Olson, the Wildcats were winners.