Months, or even years, might pass before the FBI’s investigation into college basketball translates into potential NCAA violations.

But Arizona has already begun stating its case.

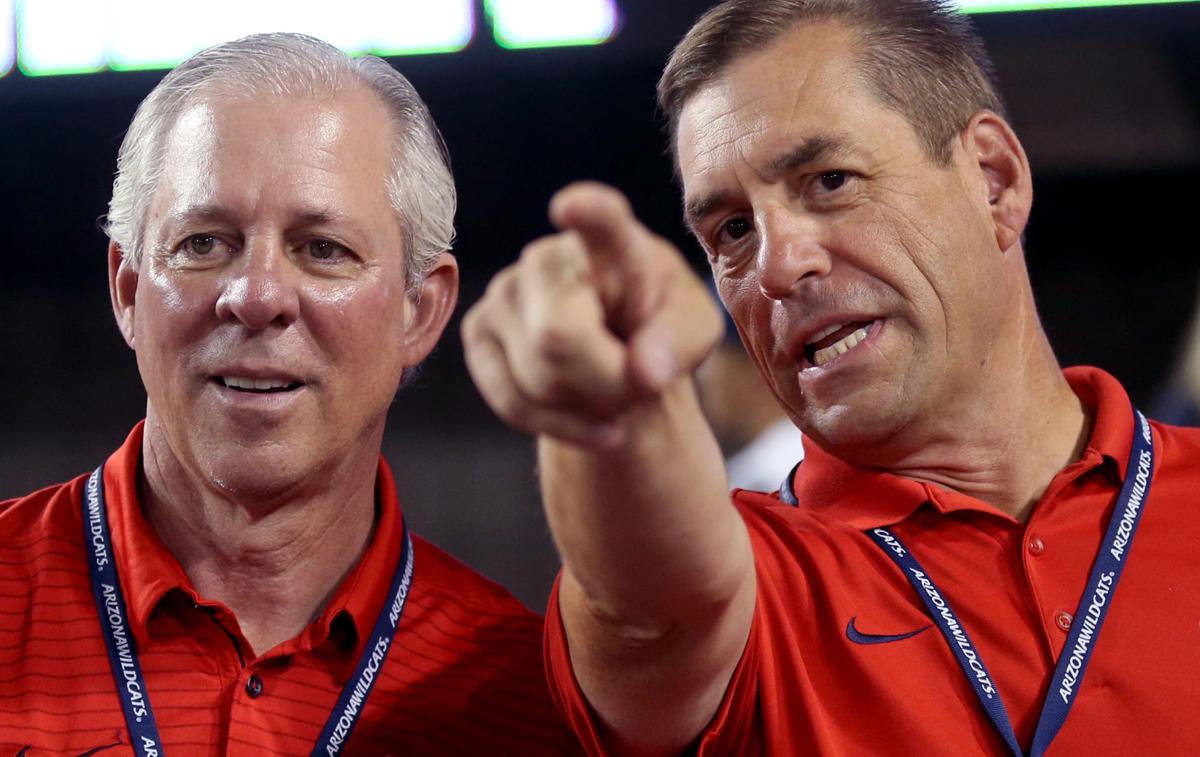

The claims last week by Arizona coach Sean Miller, athletic director Dave Heeke and president Robert Robbins that Miller has acknowledged his responsibility to foster compliance — and statements by Miller and Heeke that the UA coach has long been doing so — demonstrate the university is prepared to defend Miller under an NCAA rule that can penalize head coaches even if they aren’t aware of violations involving their programs.

Miller was not implicated in the federal complaint that resulted in the Sept. 26 arrest of UA assistant coach Book Richardson and nine other college basketball figures, but NCAA Bylaw 11.1.1.1. states that head coaches are responsible for the actions of their direct or indirect reports unless they can “rebut the presumption of responsibility.”

That rebuttal possibility, which is not mentioned in the NCAA manual but is in a supplemental guide for head coaches, can take head coaches off the hook.

Instituted in 2013, Bylaw 11.1.1.1 essentially eliminates plausible deniability and puts head coaches under a guilty-until-proven-innocent standard. In order to rebut the presumption of responsibility, head coaches must prove they have fostered an atmosphere of compliance and have actively monitored their direct and indirect reports.

“They’re making sure the coaches are engaged, so they can’t turn a blind eye to it,” said Christian Dennie, a Texas-based attorney who specializes in working with schools on NCAA issues. “If they can make sure the coach is doing the right thing, they’ll probably be OK.”

So even if the NCAA finds Richardson was guilty of taking $20,000 in bribes as alleged in the federal complaint, Arizona and Miller might not be punished if the school can prove Richardson acted on his own and repeatedly misled Miller when asked repeatedly about compliance. (There are, of course, other allegations Arizona could face as a result of the complaint.)

But it’s a difficult standard to prove. Dennie said he recommends head coaches keep emails or other written records of their monitoring efforts, having been on campuses where the head coaches “don’t fully have their heads around what the requirements are.”

The exact standard of “promoting and monitoring” is also somewhat unclear itself, according to Stuart Brown, an Atlanta-based attorney who also works with schools involving NCAA issues.

“They are supposed to do both,” Brown said via email. “It is a case-by-case evaluation by the NCAA enforcement staff and then the (NCAA Committee on Infractions). Even if a coach does most or all of the ‘checklist’ coach control items, it might not be enough.

“Also, just having your assistant coaches attend compliance meetings put on by the compliance staff isn’t enough. There is supposed to be additional compliance activity by the head coach. Plus, coaches tend not to sufficiently document what compliance activities they actually do.”

In a 10-page document the NCAA called “Responsibilities of Division I Head Coaches: Understanding rules compliance and monitoring,” the NCAA lists methods of documentation and monitoring.

Among other things, it suggests head coaches “actively look for red flags of potential violations” in such areas as asking how a recruit paid for an unofficial visit to campus or checking into prospects who are at-risk academically.

It also says coaches should ask “probing” questions of staffers.

“If a coach is suspicious of a third party or handler involved in a prospective student-athlete’s recruitment, ask probing questions of assistant coaches and other staff members,” the NCAA document says. “Emphasize the program’s ethical standards, be clear about what is acceptable in dealing with third parties and keep a written record of the conversations.”

The federal complaint quoted a sports agent saying Richardson took bribes he could use to help secure a recruit in return for assurances he would try to steer current UA players toward him for professional representation.

In recent cases involving Bylaw 11.1.1.1 and its precursors, Syracuse’s Jim Boeheim and SMU’s Larry Brown were each suspended for nine games. Louisville’s Rick Pitino was scheduled to sit out five games this season before the school moved to fire him.

Brown said Boeheim’s coaching peers considered his penalty severe, and that Pitino received his punishment even though the NCAA infractions committee found he had no personal involvement and the school didn’t receive an institutional failure-to-monitor penalty.

“Both those cases caught the attention of coaches,” Brown said. “To say that the NCAA expects a head coach to be ‘continually asking’ assistants about compliance is not too much of an exaggeration.

“To be confident about rebutting the presumption of responsibility, a head coach needs to be at least regularly be educating about, asking about, and monitoring compliance in his/her program.”

Here’s how Bylaw 11.1.1.1 has played out in recent NCAA college basketball cases, with information from media reports and Dennie’s blog at bgsfirm.com:

September 2017: Pacific

What the NCAA found: Head coach Ron Verlin improperly aided in the academic work of five athletes, including assisting prospects with coursework in order to gain eligibility at UOP.

Bylaw 11.1.1.1 implications: The NCAA found Verlin did not promote an atmosphere of compliance and did not monitor his staffers. It said Verlin admitted that he “let a couple of assistant coaches get out of control … and didn’t stop it.”

Penalties: Verlin was suspended in December 2015 and then fired at the end of the 2015-16 season. The NCAA gave him an eight-year “show-cause” penalty, meaning a school hiring him would have to offer a reason why he should not be restricted during that period. Pacific was put on probation for two seasons, ordered to pay a $5,000 fine and vacate wins that involved the players who cheated.

June 2017: Louisville

What the NCAA found: Louisville operations director Andre McGee provided strippers and prostitutes to players in a campus dorm over several years.

Bylaw 11.1.1.1. implications: Head coach Rick Pitino was charged with a failure to monitor McGee, even though the NCAA accepted Pitino’s argument that he was unaware of McGee’s actions.

Penalties: Pitino was ordered to sit out Louisville’s first five ACC games this season, although that isn’t applicable now that Pitino has been removed in wake of the FBI investigation. Louisville self-imposed an NCAA Tournament ban in 2015-16, and the NCAA added four years of probation and ordered the school to vacate wins from December 2010 through 2013-14 involving ineligible players. Pending appeal, that means Louisville’s 2013 NCAA title could be the first in NCAA history to be vacated.

September 2015: SMU

What the NCAA found: Academic fraud and unethical conduct, much of it focusing on improper help from an administrator in the coursework of Keith Frazier, a five-star recruit. It also found Brown was not initially truthful during his interview with NCAA enforcement staff, failing to disclose that Frazier and the administrator had both told him he had completed an online course that led to the fraudulent credit.

Bylaw 11.1.1.1 implications: Brown was found to have failed to provide an atmosphere of compliance, though the NCAA found Brown did not directly know about the situation.

Penalties: While SMU self-imposed a postseason ban in 2016, Brown was ordered to sit out nine of SMU’s games in 2015-16 and given a two-year show cause penalty. SMU was put on a three-year probation, ordered to pay a $5,000 fine plus 1 percent of the basketball budget and had nine scholarships removed over a three-year period. Brown resigned in July 2016 in the midst of dispute over the length of his contract.

March 2015: Syracuse

What the NCAA found: Multiple violations involving improper benefits, academic misconduct and a failure to enforce drug-testing policy.

Bylaw 11.1.1.1 implications: Under what was then known as bylaw 11.1.2.1, head coach Jim Boeheim was found to have not promoted an atmosphere of compliance or monitor the activities of his staffers.

Penalties: Syracuse self-imposed a ban from the 2014-15 postseason, but the NCAA added to the punishment. It suspended Boeheim for nine games in 2015-16, took three scholarships away from Syracuse in each of four seasons and ordered the school to vacate all wins involving ineligible players from 2004 to 2012 — a total of 108 wins.

The NCAA also ordered Syracuse to return all funds received via Big East revenue sharing for appearances in the 2011, 2012 and 2013 NCAA Tournaments — numbers estimated to be more than $1 million by Syracuse.com. The program was put on a five-year probation.