On Halloween night 2017, University of Arizona junior Thea Ramsey was home alone while her track and field teammates attended coach Fred Harvey’s annual team party.

The first-year member of the cross-country team had transferred to the UA to study in neuroscience, which her previous university didn’t offer.

While she was studying she received — and ignored — a phone call from a male teammate with whom she said she had an uncomfortable encounter the week before and had asked him to leave her alone. Then several more calls. Then he started banging on her doors and windows.

“I locked the doors and windows, turned off the lights and hid,” Ramsey, now 22, told the Star.

She reported the teammate to her coaches the next day and said she was shocked that no one seemed particularly concerned, even though she had told coaches just a week before that he had kissed her without consent while the two were studying, then threatened to hurt himself after she pulled away.

The coaches took no action, she said, and the male athlete was allowed to keep competing even as other team members reported him to coaches for sending a naked Snapchat video and making disparaging comments about sexuality and about people living with disabilities. He was finally dismissed from the team in early 2019 after a different student took out a protective order against him.

Ramsey is one of eight women — all former members of the UA track and field team — who contacted the Arizona Daily Star earlier this summer to detail incidences of sexual harassment, bullying and even assault by teammates, both women and men. They said their complaints were dismissed by coaches, who often attempted to discourage victims from telling teammates, friends and family members what they were experiencing. In several cases, they said, coaches failed to report allegations of sexual discrimination to appropriate authorities as required by federal law.

Among their claims:

- Female athletes were subjected to public weigh-ins and required to track food and calories consumed — practices experts say can cause and perpetuate eating disorders.

- Some runners were pushed by coaches and support staffers to overtrain, often while injured, raising their risk for injury or permanent damage.

- Less successful athletes were ignored or punished for breaking minor rules, while some more successful athletes were given repeated passes for breaking team and school rules.

- Serious mental health issues were neglected or glossed over by coaches.

The women say they’ve been sharing these concerns with athletic department officials for years, and that last month, the school finally launched an investigation into the program.

One expert described the athletes’ allegations as the makings of a “rotten culture” where physical and mental health are overlooked, abusers are protected and victims are bullied into silence or told they’ll harm the team culture if they speak out.

The women who came forward, six of whom asked to remain anonymous because of the nature of their experiences or fear of retaliation, corroborated each other’s claims, and in many cases, provided witnesses and documentation.

None of them has sued the UA and all say they don’t intend to do so. They say their goal is to elicit change in the program and to ensure the safety of future women on the track team.

UA officials said in a statement that while they are “not able to comment specifically on any personnel or conduct matters ... there have been administrative and roster changes” and that the athletic department will “continue to adjust to meet our goals for the program.”

“I sincerely regret that these student-athletes’ experiences did not meet their expectations or our expectations for them,” athletic director Dave Heeke said in the statement.

UA officials respond

The women who approached the Star said they don’t know how the team’s culture came to be this way. Most of them said they were treated most harshly by assistant coach Hanna Peterson, a former member of the team who became a coach in 2018.

They said Harvey would often cry when discussing serious issues, like harassment or abuse, with the team, but that the tears or sentiment did not seem sincere. They acknowledge that numerous athletes report a positive experience competing under Harvey, who has been with the UA for 33 years both as an assistant and head coach.

Longtime UA track coach

One of those athletes was Georganne Moline, a sprinter and hurdler who trained under Harvey at the UA and beyond, earning a spot in the 2012 Olympics when she was a junior.

Moline said that coming onto the UA’s track team, she wasn’t a top performer, but Harvey worked with her to improve her skills. She said he was always kind and understanding, and in the years since, has become like a father to her.

“Coach Harvey would never allow unethical behavior to take place on his team. The situations may have not been handled in the time frame people expected them to but they were ALWAYS addressed. Conversations were had, student athletes were suspended, and a student athlete was kicked off the team and sent back to his home country,” Moline said in a text message to the Star. “Coach Harvey is the head coach of this institution but more importantly, he is a man of integrity and will always stand for what is right.”

The Star asked to speak with Harvey, Heeke and UA President Robert C. Robbins about the allegations. The UA instead sent a statement from Heeke.

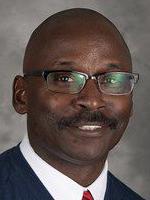

Athletic director Dave Heeke says he has a "great sense of empathy and compassion" for employees who will lose their jobs because of the pandemic.

“Arizona’s Athletics Department is committed to fostering a healthy and safe learning, working, and living environment where all student-athletes and staff are free from discrimination and harassment,” Heeke said in the statement. “To be very clear, the allegations presented are profoundly contrary to my expectations.”

The UA’s athletic department regularly requests feedback from student-athletes regarding their experience at the school, and those responses are “encouraged, valued and thoroughly reviewed,” the statement said. Further, in 2019 the track and field program launched “culture building workshops” that are ongoing. The UA would not share topics or dates or say whether attendance was mandatory.

In regard to the women’s allegations: “When we have received information that someone could have violated University polices, it was acknowledged by our staff and shared with the Dean of Students, the Office of Institutional Equity, or department leadership, as appropriate. Responsive administrative actions have included personnel decisions, professional training and team-building activities, student support, and coordination with appropriate University offices.”

Due to privacy considerations, students might not be made aware of the outcome of actions, the statement said.

UA officials wouldn’t say how many roster changes had been made in recent years and how many members of the program had been disciplined for sexual harassment or abuse.

“The university does not publicly release information on student conduct inquiries to avoid unforeseen and adverse consequences that could affect victims and witnesses and to protect the integrity of the process,” the statement said. “We have absolutely not asked a student-athlete to remain silent or be uncooperative with campus partners conducting policy reviews.”

An athlete speaks out

The women’s allegations come on the heels of another track and field scandal. In 2015, throws coach Craig Carter was arrested for assaulting and threatening the life of a thrower with whom he was having a sexual relationship.

Carter was convicted of aggravated assault in 2018 and is now serving five years in prison. In April 2019, the UA paid nearly $1 million to settle a lawsuit with his victim, Baillie Gibson. The state also paid more than $2.5 million to defend Carter in the lawsuit, as he was a state employee at the time that the incident took place.

Even after Carter’s departure, other coaches continued to treat some athletes on the team badly, the eight women told the Star. Over time, current and past track athletes started leaning on one another for support, they said.

“We became closer because we were often injured together, because we held each other after meetings with the coaches left us feeling hopeless, and sometimes it felt like we were the only ones cheering each other on because the coaches usually were not,” Ramsey said.

Ramsey, a May 2020 graduate, and Hannah Whetzel, who graduated in May 2019, shared their concerns with coaches and athletic department officials multiple times dating to 2018, according to records shown to the Star, but no action was taken. On June 27, Ramsey emailed Heeke, whom she knew through her role as president of the Student-Athlete Advisory Committee.

Heeke never responded, Ramsey said. But shortly after she sent the email, she said her name and photo were removed from the team’s roster, as were the names and photos of three other women who sent notes detailing their experiences.

During her time at the UA, runner Hannah Whetzel said she suffered injuries that were not handled properly by coaches and the medical staff.

On July 8, Whetzel emailed Heeke, chief operating officer Derek van der Merwe, executive senior associate athletic director Erika Barnes and senior associate athletic director James Francis. She forwarded the email to UA President Robert C. Robbins.

Whetzel told the UA officials they were “completely aware” of what was going on withing the program “yet refuse to take action, because protecting the university’s reputation is apparently more important to you than the safety and physical and emotional well-being of your student-athletes who create that very reputation.

“You know what you’re doing, you know what you’re hiding, and unfortunately for you, so do I,” she wrote. “So do a lot of us.”

The next day, Whetzel contacted the Star.

On July 17, Whetzel received an email from Heeke, saying he’d shared her communication with the Office of Institutional Equity, which investigates complaints of discrimination levied against UA employees. Whetzel said she was contacted by the OIE on July 16, the day before she received Heeke’s email.

Heeke said in the email that the university was taking her concerns seriously and that they were “carefully reviewing the other concerns (she had) raised about the program.”

The UA would not confirm the investigation, saying that it has “long-maintained a practice of not commenting on active OIE investigations” because that “could erode faith in the OIE process, impact respondents’ rights, and potentially, interfere with the integrity of the investigative process.”

Maksims Sincukovs, a 2018 first-team All-American in the 400-meter hurdles, was expelled after being found responsible for four violations, including endangering/threatening/causing harm, stalking/unwanted contact and discriminatory activities.

'My teammates were at risk'

Two years after Ramsey’s Halloween night terror, one of her teammates experienced a similar incident involving a different teammate.

Only this time, the man would be successful in gaining entry to the woman’s home.

At 5 a.m. on Aug. 24, 2019, Maksims Sincukovs — a 2018 first-team All-American in the 400-meter hurdles — broke into a female teammate’s apartment, kicking through her window and blocking her from leaving, according to UA and Pima County Superior Court records.

Sincukovs had not been invited and was “incredibly intoxicated,” touching the woman’s shoulders and arms as she begged him to leave, court records show.

In her petition for an injunction against harassment — which was granted, appealed and upheld — the woman said that Sincukovs had harassed her in the past and she had made it clear that she was not interested in him. The Star does not identify victims of sexual harassment and abuse unless they consent to be named.

“After countless minutes of crying and begging him to leave, he left,” the woman said. After the attack, she started having panic attacks and her grades fell, she said.

The woman notified police and requested an order of protection as soon as she was able to, the Monday after the Saturday morning incident. She then contacted the UA’s Title IX office, which investigates sex discrimination claims, including sexual harassment and abuse.

Hours after the incident, she notified Harvey; head cross-country coach and assistant track and field coach James Li; and assistant coach Peterson, who replaced Tim Riley as the assistant men’s and women’s cross-country coach and track and field distance coach in 2018. Peterson ran at the UA, graduating in 2016 before joining the coaching staff.

The woman said the day after the break-in, coaches required her to receive an award at the student-athlete ceremony at McKale Center, where Sincukovs would also be in attendance. The woman said Harvey dismissed her concerns, saying other men from the team would be present and therefore she’d be safe. Peterson suggested she hide in her office before and after receiving the award, the woman said.

The woman said Sincukovs was told not to attend only after a relative called Harvey to express his concern for her safety and the coaching staff’s lack of professionalism.

Text messages show Harvey later contacted the woman to ask for her schedule so he could make sure Sincukovs could still access the UA’s facilities without violating the court order, saying he’d make sure they didn’t cross paths.

“That message from Harvey is just one example of many, reflecting a pattern of protecting perpetrators on the team over the victims,” the woman said. “Sacrificing the safety of the people who needed them the most.”

Text messages show that Harvey also asked her not to discuss the situation with anyone on the team.

“That’s inappropriate coming from a head coach. The only people who could ethically inform me of the justice process was the Title IX office or police,” the woman said. “By not talking about it, my teammates were at risk.”

A few months later, during a Title IX investigation, the woman says she was told by an employee in the dean of students office that she was allowed to tell her teammates what happened.

It was during that investigation that the woman learned Harvey had written a letter of recommendation for Sincukovs to transfer to Clemson.

When she did come forward to her teammates — three months after the break-in — she said she was told that Sincukovs had harmed other women on the team.

Not all her teammates were supportive. She said a male teammate wrote on a team text message thread that she was lying and had been asking Sincukovs and other men on the team to come over that night. She shared the message with her coaches, and said the teammate not only went unpunished, she said, but was bumped up to team captain for an upcoming meet.

The dean of students’ investigation ultimately determined that Sincukovs broke in “with the intent to engage in sexual activity” with the woman, UA documents show. He was found responsible for four violations, including off-campus conduct, endangering/threatening/causing harm, stalking/unwanted contact and discriminatory activities. He was expelled from the UA and then unsuccessfully appealed the decision.

On March 6, a UA panel upheld a November decision by the dean of students office to expel Sincukovs for multiple code of conduct and Title IX violations. Title IX is a federal law that guarantees all students have access to an education free from discrimination, of which sexual harassment and abuse is considered.

Recent social media posts indicate that Sincukovs has returned to his home country of Latvia.

UA officials declined to say if any other student-athletes had been dismissed from the track team for Title IX violations, citing federal privacy laws. Those laws include an exemption that allows administrators to disclose the name, violation and consequences for any student disciplined under Title IX.

'Gaslighting'

Another former runner said she was mistreated by a female teammate to the point that she became dangerously depressed.

Throughout the runner’s freshman year, the teammate would make threatening statements — including self-harm if the woman beat her in a race — and get angry if she spent time with other girls on the team, the runner said.

By the spring of 2019, the runner — who has since transferred to a new school, seeking a fresh start — said she took her concerns to Peterson, who was in her first year as assistant coach. The runner said Peterson advised her to stay friends with the teammate, warning that she could ruin the team culture otherwise.

The runner began working with an athletic department psychologist, who she learned was also treating the teammate harassing her. The runner eventually found her own therapist, outside of the school.

Ramsey said that shortly before spring break, the runner confided in her about the situation. Ramsey said she tried to tell Li that she believed the woman needed help but was interrupted by Peterson, who told her to mind her own business.

The situation continued to get worse for the runner. In spring 2019, she says she began thinking about hurting herself. She sought treatment and went home early for the summer. As upset as she was at her teammate, the runner ultimately blames the coaches for the situation.

The runner returned in the fall, determined to keep her head down and focus on her sport. She said that while she was a high performer, the coaches rarely spoke to her and she felt neglected.

Recognition by the athletic department for her high scholastic performance wasn’t acknowledged by anyone on the coaching staff, she said.

That sentiment is echoed by the women who spoke to the Star, several of whom said they felt invisible after reporting misconduct by teammates or when they were battling injuries or trauma.

“Mental health is kind of neglected on the team,” the runner said. “The coaches kind of gloss over it and don’t really see it as a big thing.”

In January, she said, she was called into Li’s office for what she hoped would be a one-on-one meeting. Instead, Peterson and the teammate she’d had issues with the previous season were also there. The woman said she was told they needed to be friends.

Things finally came to a head when she was called into Harvey’s office in the spring after she shared her concerns in a letter to the coaches. At the meeting, she said she was told she would sit out the first two outdoor meets and was scolded for not delivering a sincere-enough apology to two of her teammates for suggesting that they all run together instead of the two teammates running by themselves. She said she left the meeting in tears, went immediately to take a midterm and later that day, had to travel with the team for the indoor conference championships. Members of the cross-country team, including this runner, often compete in the spring track season as well.

“One word that would sum up my entire experience was gaslighting. They convince you that you’re the one that’s in the wrong,” the runner said. “I had all these authoritative figures telling me that there was something wrong with me. I was blaming myself even though it wasn’t my fault.”

Several of the runner’s teammates told the Star that they tried to share their concerns for her well-being with Peterson but were told it was not their business or were directed away from the conversation.

Assistant

coach, ex-UA athlete

One teammate said Peterson told her that she was a leader on the team and to not let the situation affect team morale. The teammate, who has since decided to quit the team, says that after being treated poorly by the coaches for years, Peterson’s words meant a lot to her. “For someone who was at the bottom of the list for so long, compliance was tempting,” she said. “But this individual was my friend.”

The runner’s father told the Star that watching his daughter suffer from a distance was the most trying time of his parenting life. He said he met with his daughter’s coaches to address the forced apology, to ensure that no one would try to impede her transfer to another program.

He said that during the meeting, Peterson said nothing and Harvey’s statements felt scripted.

“That, to me, is indicative of what goes on behind the scenes and the front that they put up when parents come to intervene,” the runner’s father said. “It reeks of retaliation, and they had no remorse.”

His daughter will attend another university this fall.

During her time at the UA, runner Hannah Whetzel said she suffered injuries that were not handled properly by coaches and the medical staff.

Physical health

When Whetzel arrived at the UA in the fall of 2015 as a cross-country walk-on, she had previously struggled with an eating disorder. During her time at the university, she said the eating disorder returned and she suffered injuries that were not handled properly by coaches and the medical staff.

Whetzel said that while her experiences were unique to her, disordered eating and mismanaged or overlooked injuries were frequent among her teammates.

She said an athletic department nutritionist she saw her freshman year insisted she measure and track her food, and would scold Whetzel if she ate fatty foods. At the time, the 5-foot-6-inch athlete weighed around 110 pounds.

After redshirting her first year, in April 2016 Whetzel suffered a stress fracture to her fibula during a run. She knew instantly something was wrong, telling her trainers that she thought she broke her ankle. She said they dismissed her claims, saying she’d know if it was broken and she’d feel better the next day.

After days of painful treatments for what trainers told her was an issue with her tendon, an orthopedist diagnosed a stress fracture. She eventually healed but was injured several other times during her years at the UA — and each time, she said, her coaches acted like she wasn’t even on the team.

“I felt alone and isolated,” she said. “Your coach is the person that you’re supposed to trust the most, and you think that they always have your best intentions and want what’s best for you. But when that person treats you like you don’t matter, you start to believe it.”

During her senior year, Whetzel suffered another stress fracture, this time to her shin.

“When my coaches found out about my shin fracturing, I felt like I was being attacked and made to feel as though it was my fault for not doing more to prevent it,” Whetzel said. She had been following their training and running less whenever possible, knowing something was wrong. “I ran on a fractured shin for 3½ months and my coaches never once asked me if I wanted to stop. I knew I could not complain.”

By the end of the season, Whetzel said she had convinced herself her shin wasn’t broken and didn’t hurt because that’s what she had to do to keep running.

“I was terrified before the start of every run that my leg would snap, and during races I repeated in my head, ‘Please don’t break, please don’t break,’” she said.

At about that time, Peterson — her former teammate — was named the team’s new assistant coach.

“When I found out she was going to be coach I started crying because I knew she didn’t like me,” she said. “It just got worse. As a coach, everything is so fear-based. She had so much control over if we could race. She just controlled our lives.”

Peterson changed rules and expectations without notification and controlled runners’ activities outside of school, Whetzel said. She even tried to control what athletes posted on social media and who they were allowed to hang out with, Whetzel said.

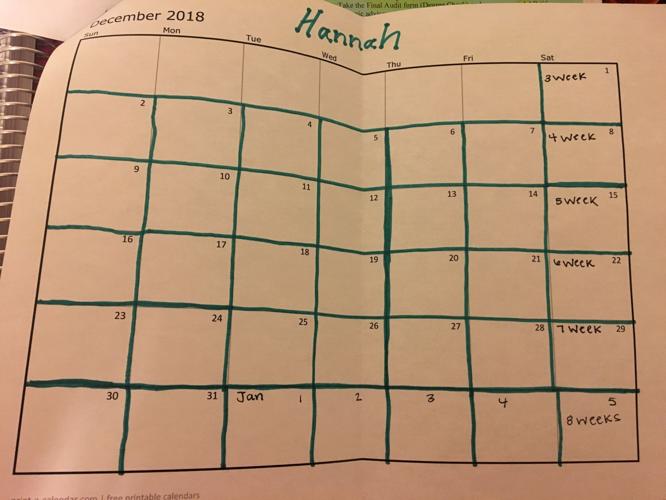

This blank calendar page was sent home with UA cross country runner Hannah Whetzel by her coach, Hanna Peterson, over winter break in 2018. Whetzel said that all other members of the team, even those who were injured, were provided with a daily training schedule.

When Whetzel went home for winter break, Peterson gave her a blank training plan, while sending all other cross-country team members — both injured and healthy — detailed plans for what to do each day to stay competition-ready. Whetzel said the blank calendar page reinforced her feelings that she wasn’t worth Peterson’s time.

“At first I thought it was a mistake, but when I went in with my friend to pick hers up the next day Coach Peterson told me she already gave me my plan,” Whetzel said.

At an appointment with an athletic department doctor in February 2019, Whetzel said her eating disorder was obvious and she was also showing signs of a syndrome called relative energy deficiency in sport, which the International Olympic Committee characterizes by anemia, weight loss, low hormone levels and loss of period, anxiety and multiple stress injuries.

“Instead of offering me help, the doctors lied to me by telling me everything looked good and allowed me to continue what I was doing,” Whetzel said. “My coaches encouraged my rigorous overtraining.”

Shortly after that, Whetzel was called into Peterson’s office and told that people who say bad things about the team would be suspended, which she felt was a threat for speaking out. In the same conversation, Peterson also said that the UA had a scholarship open and that she’d recommended Whetzel for it.

Whetzel interpreted the conversation as an offer of money to keep her mouth shut about the problems on the team. She never received a scholarship.

“I felt like I couldn’t tell anyone what happened because that would make me just as bad as she said I was,” Whetzel said. “Prior to this meeting, I already believed I was the source of all my own problems, but Coach Peterson made me feel as though I was the source of everyone’s problems.”

Whetzel left the meeting feeling trapped and like she would not be able to make it to graduation. She said that’s when she starting having suicidal thoughts.

“I had thought it was all my fault, because I had issues before I even came in. I didn’t realize that what they were doing was causing the problems. Maybe I’m predisposed, but this happens to a lot of people.”

By the end of her time at the UA, Whetzel’s eating disorder was so bad that she didn’t even eat at her own graduation party.

Shortly before leaving the UA, Whetzel said she sent a seven-page letter to Harvey and Peterson detailing her experience. She also discussed her concerns in a meeting with Francis, the senior associate athletic director.

Whetzel has since received records of her bloodwork and bone scans from her time at the UA. Doctors have told her she was showing indicators of malnutrition and that her bone density was decreasing throughout her time on the team.

“I haven’t run in eight months, she said. “I can’t separate what I experienced in college from the sport itself. Now I don’t know if I want to run anymore.”

Athletes felt betrayed

The day after Halloween 2017, Ramsey said she met with then-assistant coach Riley to tell him about her teammate showing up at her house uninvited the night before. Instead of asking if she was OK or needed any help, Ramsey said, Riley told her to make sure she didn’t find herself in the wrong place at the wrong time.

“That was confusing because I was at my house,” Ramsey said.

Not satisfied with the response, Ramsey says she went to Li, who she had also turned to the week before after the teammate kissed her unsolicited and told her afterward that he was having suicidal thoughts.

Li had asked Ramsey if she was OK when she reported the Halloween night incident, but he didn’t seem to do much else with the information, she said.

The teammate remained on the track and field team.

Ramsey said she told Harvey about both incidents involving the teammate during an in-person meeting on April 25, 2018. She said that she assumed her coaches had fulfilled their legal obligation as mandatory reporters and told the appropriate UA authorities about the situations involving her teammate, but she later learned that was not the case. Several months after reporting the incidents to Harvey, she took out a no-contact order against the teammate for a separate situation.

Beyond that experience, Ramsey said she was treated harshly by Peterson and forced to train with injuries. In May 2018, she provided feedback on her experiences through the school’s end-of-year reporting form, and followed up with Barnes, the Wildcats’ senior associate AD.

“Some of (your comments) are extremely concerning,” Barnes wrote back in an email, in which she copied an employee of the dean of students office, telling Ramsey that person would be the next step in sharing more information. “Please know that we are here to support you and make this a positive student-athlete experience.”

Barnes closed the email by saying she would follow up with Ramsey later. Ramsey said she never heard from Barnes or anyone from the dean’s office.

After cross-country camp shortly before the start of the semester, Ramsey was asked to provide evidence in an unrelated Title IX hearing involving the teammate who had shown up at her house the year before. It was then that she learned the office had never received any reports about sexual harassment she had endured the previous year, a violation of her coaches’ mandatory reporting duties.

Ramsey said — and emails confirm — she tried again in May 2019 to give feedback about her experiences in the track and field program, asking Barnes if she could remain anonymous. She was told there was no way to provide anonymous feedback.

Ramsey returned in the fall with a plan to change things herself. She was president of the school’s Student-Athlete Advisory Committee.

In the committee’s first meeting, Robbins — the UA president — talked about how the UA athletic department was being compared to Michigan State’s because of recent news coverage regarding Title IX issues within the athletic department, Ramsey said. Michigan State had settled lawsuits with the victims of former trainer Larry Nassar.

“I remember thinking, ‘They know that it’s like this,’” Ramsey said.

At a later meeting, a UA employee presented information about the school’s Academic Progress Rate, which Ramsey said was also illuminating.

A school’s APR measures attrition of scholarship athletes from each sport. Basketball and football teams usually have low relative APRs because of the likelihood of players to transfer to other schools before graduation.

From 2014 to 2019, NCAA cross-country teams reported an average APR score of 989. In the Pac-12, the average was 988. During the same time period, the UA’s combined men’s and women’s cross-country team had an APR of 955 — by far the lowest of every sport at every school in the Pac-12.

Schools are encouraged to take action any time a sport’s number falls below 980. But at that meeting, Ramsey said, there was no further mention of it.

In the spring of 2020, Ramsey said, the women’s cross-country team had regular, public and mandatory weigh-ins that were not conducted by anyone on the medical staff.

At first, they weren’t given an explanation for the weigh-ins — which were often done in front of members of other teams, with a digital weight readout large enough to be read from a distance. But after asking several times, the women were told their weight was being used as “part of a way to measure performance,” Ramsey said.

“Girls would talk about how they wished they hadn’t eaten breakfast in earshot of the coaches,” Ramsey said, adding that she began turning around after she stepped onto the scale, saying she didn’t feel comfortable seeing her weight every week. Eventually, the staff requested they all turn around.

The women’s team was subjected to different practices than the men’s team in other ways, too: Weekly training rosters showed the majority of the women’s team was assigned extra weekly “cross training” hours, while members of the men’s team were often assigned none. When asked why they were required to complete upward of six extra training hours per week, they were simply told “it will make you better.”

Ramsey sent in her end-of-year feedback again in May. Francis responded, saying her notes had been sent to the OIE and the athletic department’s human resources division and that moving forward, she would likely not be provided with any updates on the review.

She decided to take her concern to Heeke, who she’d known since 2018 from their time together on the student-athlete advisory committee, as well as the athletic department’s coronavirus task force.

Ramsey said Heeke still hasn’t responded.

“We were taught to trust in the coaches and trust in all these systems that they would protect me the way that they were supposed to. I think they benefit from that,” Ramsey said. “Every time they have failed us it was to benefit the reputation of the athletic department. And it always comes at the cost of people like myself.”

Ramsey said that after years of trying to report her concerns to the UA, she came to believe that the athletic department didn’t want to hear anything negative and chose to ignore it.

“I did as much as I could to help other women while I was there. Being SAAC president and being on committees, I was trying to so hard to protect and advocate for people,” Ramsey said. “I felt like I couldn’t walk away from this school knowing that there will be other women put into this system.”

Victoria Jackson, a sports historian at ASU, says she was a white athlete who benefited from a broken system. She was a championship runner.

“Healthy culture,” winning can coexist

One expert in both college athletics and distance- running culture said she was not surprised to hear about issues within the track and field program, given that there was no change in the program’s leadership after Carter’s arrest and incarceration.

Victoria Jackson, a sports historian who teaches at Arizona State University, was a distance runner at both North Carolina and ASU.

Last summer, Jackson was the keynote speaker at the UA’s Controversial Issues in Higher Education symposium, talking about the dangers of amateurism. At the time, Jackson said the power athletic departments yield makes them ripe for scandal.

“When there’s one scandal going on or one abusive practice going on, typically when you start looking deeper, there’s more,” Jackson said. “If it was just one thing, it would have been addressed in a healthy culture.”

Some issues, such as eating disorders and depression, are common in endurance sports, but it’s all about how coaches and support staff handle those issues, she said.

In November, track star Mary Cain came forward with allegations of abuse within Nike’s Oregon Project, saying the all-male coaching team’s training methods harmed her body and threatened her mental health. Jackson said earlier this month that hearing about the situation within the UA’s track program is one reason Cain’s speaking out was so important.

“She spoke about it in a way that forced a reckoning in endurance sports culture,” Jackson said, adding that in the 1980s and 1990s, bad coaches and an unhealthy culture ran rampant.

“Now, there are a lot more people leading and doing the work to build healthy cultures in distance programs. But there are rotten cultures still, and (the UA cross-country team) certainly sounds like a rotten culture.”

Jackson said that under the current state of amateurism, athletes have no power and coaches are not held the same standards as other state employees. In competitive athletics, there’s a dangerous mentality among some coaches that any distraction or critical thinking could detract from the ultimate goal of winning, she said.

“Actually, you’re working against that project of winning,” she said. “You can’t win when you don’t have a healthy culture.”

Expert: Coaching must change

Joan Steidinger, a clinical and sports psychologist who has worked with abuse victims since the 1980s, said the issues the UA runners experienced are fairly common among female athletes for a variety of reasons, including what she calls “old-style abusive” coaches.

“Parts of the country are working to get rid of that, but there’s still a lot of ignorance that goes on in terms of covering up in every sport, and particularly on super-competitive teams,” Steidinger said.

Joan Steidinger wrote “Stand Up and Shout Out”

In March, Steidinger’s book “Stand Up and Shout Out” was published. It examines three areas in sport that remain problematic for women: leadership, money and media coverage.

“Coaching was originally so rough and tough, they don’t always take the time to see that rough and tough isn’t always the best solution,” Steidinger said. “It’s like stepping back and trying to have compassion for people — especially — is too time-consuming.”

Another reason abuse is common in college athletics is the lack of enforcement at higher levels, she said.

“Even at the Olympic level, they aren’t enforcing protection for women,” Steidinger said, adding that SafeSport, the nonprofit oversight group established to end abuse in sports, is “just scratching the surface.”

Poor representation of women in leadership roles also doesn’t help; Only eight of the top 90 running coaches in the country are women.

“And that doesn’t mean that they’re women that treat women with respect,” Steidinger said. “That’s the problem: Men still believe they can abuse women. And with athletes, that power dynamic is built into the system.”

Widespread change is the only solution, Steidinger said.

“If you don’t change the whole structure and get people in there who are more progressive, they end up repeating the same thing all over again,” Steidinger said.

People need to keep talking about these issues, she said. “Otherwise it comes to the fore, gets in and then dies out again.”