Not many of us are as lucky as Brett Weber.

For one, he was born on St. Patrick’s Day, so you could argue he was born with a four-leaf clover in his bassinet.

But then there are the second chances. Plural.

Not many of us are blessed with one second chance, much less two.

The first one saved the Arizona football program.

The second second chance may just have saved Weber’s life.

• • •

The second-most impressive athletic feat of Brett Weber’s life came not much earlier than the greatest.

It was 1979, and Weber was a freshman at Arizona. Early in the school year, he befriended another freshman named Steve Holmes. They were your typical freshmen: Holmes an engineering major, Weber a business major and walk-on kicker on the Wildcats football team. They hung out, listened to music — and competed at everything, as 18-year-olds are wont to do.

Holmes lived in a dormitory at the southwest corner of the football stadium, with a basketball hoop facing Sixth Street. One day they were shooting hoops, and Holmes bet Weber a 12-pack of beer he couldn’t make the shot from across Sixth, more than a full-court heave.

“And he made it. He sank it,” Holmes said. “I thought, ‘Holy crap, he’s clutch.’ ”

Weeks later, Weber would prove it.

• • •

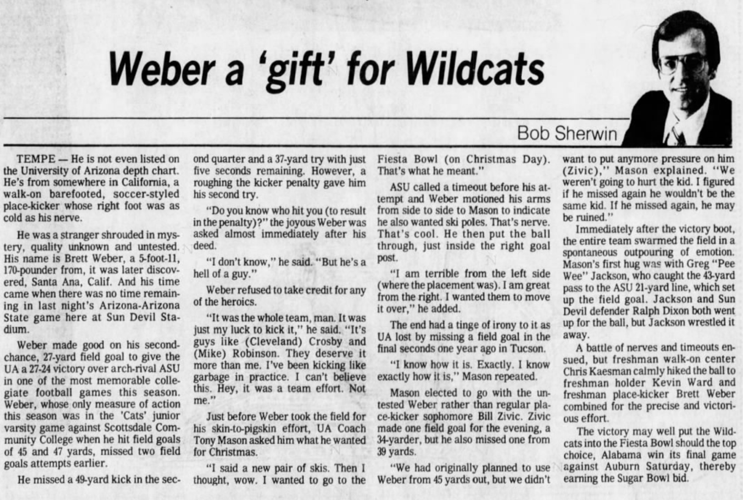

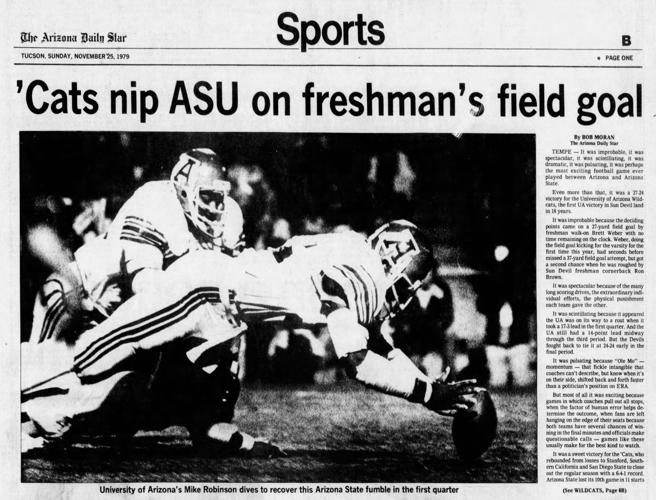

Nov. 24, 1979, was a banner day in Arizona football history.

In the 15 seasons before then, ASU dominated the rivalry. The Sun Devils of the 1960s and ’70s were perennial powerhouses under head coach Frank Kush and regular tormentors of the Wildcats, whom they defeated nine straight times from 1965-73 and another four straight from 1975-78.

But earlier that season, Kush was fired in disgrace after stifling a school investigation into allegations that he had mentally and physically abused former punter Kevin Rutledge. Just four years removed from a 12-0 1975 campaign and a No. 2 finish, and coming off back-to-back 9-3 campaigns, the Sun Devils slipped to 6-4 by the time Arizona came to town that late-November day.

The Wildcats were just trying to find their footing under Tony Mason.

The third-year coach had led them to 5-7 and 5-6 records in his first two years. Arizona was 5-4-1 in 1979, and a win over the Sun Devils would ensure Arizona’s first winning season since 1975. Every UA-ASU rivalry game is the biggest of the year, but this one mattered even more.

For much of the game, the Wildcats looked like they would give Mason his signature win and the school its first victory in Tempe since 1961. By midway through the first quarter, Arizona was up 17-3, and the Wildcats still led by two scores by the middle of the third quarter. The Sun Devils, led by quarterback Mark Malone, stormed back to tie it by late in the fourth quarter, 24-24.

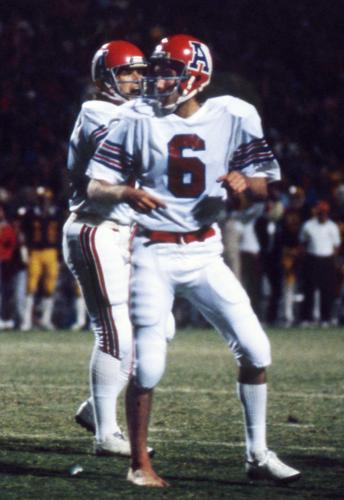

Weber stood anxiously on the Arizona sideline as the time dwindled.

Sometime during the week, Weber — a freshman walk-on kicker whose name wasn’t even in the program that day — was told by coaches that if it came down to it, he’d be the one to take a potential last-second field goal attempt. A year earlier, in the 1978 Territorial Cup, freshman kicker Bill Zivic had missed a 45-yard field-goal attempt with five seconds left on the clock, and the coaches told Weber that they did not want to put Zivic under such scrutiny again.

Weber can’t recall exactly when he was told he would be taking the kick, but he remembers being told to be prepared.

“And so I was prepared,” he said. “I was afraid, but I figured if I go through the motions, I should be fine.”

Weber watched as Wildcats linebacker Jack Housely intercepted Malone with 33 seconds left, and he knew the spotlight would be shining on him.

Up in the stands were members of his family — Weber was told later his father was ducking under the seat, too nervous to watch — and Weber’s friend, Holmes. Holmes remembers seeing his buddy run onto the field with five seconds left.

“I knew Brett was a pretty good kicker, but I didn’t have a sense that the game would come down to him making it or not,” said Holmes, who is still a UA season-ticket holder. “The rivalry was pretty hot, and as a freshman, it was fun to be a part of it. I knew he was a good athlete — not just a kicker, he was a really good athlete — and I just thought, ‘Boy, this is your big opportunity.’ You’re always worried if your friend misses it, he’ll be the goat.”

And for a moment, Weber was.

• • •

With five seconds left on the clock and the ball on the 20-yard line, Weber lined up to kick — barefoot, as he always did. He had had a nasty habit of hooking the ball in recent weeks, so he wanted to compensate. He took his steps, lined up, booted it … and missed.

“I didn’t choke,” he says now. “I just missed. I kicked it right where I wanted, and it missed. It didn’t hook.”

But alas, a reprieve.

As Weber came down for his follow-through, he saw a snarling defender — Arizona State cornerback Ron Brown — barreling down on him. He braced for impact.

“That was comedy in itself,” he said. “You aim it, you shoot it, you say, ‘Crap, I missed,’ and you see a guy hating your soul coming at you, and if you’re smart enough, you make sure you take a step forward. As I’m falling, I’m yelling to the ref, ‘You saw this! You saw it, right?’ ”

Weber laid there for what felt like an eternity, hoping his emotional performance would do the trick, if not win him an Oscar.

Then, a penalty flag. A do-over. A chance at redemption.

This time, Weber de-compensated for the hook.

“I lined up a foot or two on the inside this time, so in case I hooked it, it went through the middle,” he said. “I kicked it straight and made it through by two feet.”

He was a hero.

“That was pure, slow-motion weirdness, on the bottom of a pile,” he said. “Freaking unbelievable. That was absolutely cool. We took the bus right home. Everyone was celebrating. I got back to my dorm at Cochise, and on a chalkboard it said, ‘Weber Wins It!’ But everyone was in bed, so I just went to bed.”

• • •

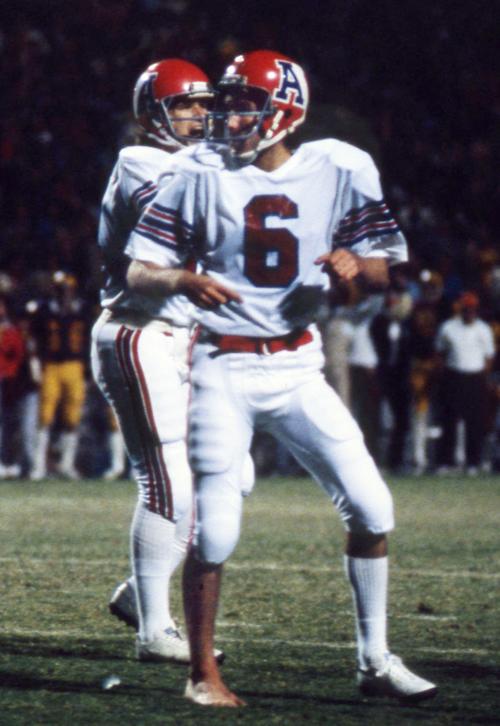

Arizona's Brett Weber kicked the game-winning field goal over ASU in 1979.

The kick that went in, Weber says, is almost a blur.

So often, we remember the failures in life more vividly than the successes. The make is but a memory, but the miss will stay with him forever.

“I remember in slow motion the miss,” he said. “I remember the guy’s face yelling at me, wanting to pound me. I’m proud of myself for getting that flag.”

Holmes remembers being up in the stands, cheering, a sense of overwhelming relief washing over him. He wasn’t friends with the goat.

“He’s clutch. I’m telling you, the guy is clutch,” Holmes said. “He drilled it, and he put a dagger in ASU’s heart.”

Thirty-eight years later, it was Weber’s heart in need of healing.

While taking a Father’s Day hike with his sister two years ago, Weber experienced some chest tightness. Earlier that week, Weber — a successful commercial real estate broker in Silicon Valley for more than three decades — had been doing some work on a construction site. He’d pulled down on a bar and felt some pain, so when he experienced more discomfort, he chalked it up to that. Later that week, he went swimming. More pain — this time more significant — prompted Weber to see a doctor.

Weber had a 90% blockage in one artery. He needed surgery, with two stents necessary.

Afterward, his doctor told him just how perilous it was.

“They call it ‘The Widowmaker,’ ” Weber said. “I said, ‘Great, now you tell me.’ ”

Second chance No. 2.

• • •

That Weber was even a Wildcat in the first place is a story.

He had played soccer and pole-vaulted in his early years of high school, but the football coach coaxed him out to be a kicker his senior year. He enjoyed and had a big leg, so he wanted to try out for the Wildcats.

His father took him to tryouts, where there were a half-dozen other players just standing there. He didn’t want to go in. They waited for a half-hour. They couldn’t figure out where everyone went. Someone asked a guard. They were at the football stadium, not the practice field.

“It’s football! We were at the stadium! Tryouts have got to be at the stadium right?” Weber said. “I run to the old field, run into the gates, see a dozen guys kicking. I said, ‘You’ve been here a half-hour?!’ I’m putting the ball down. I just starting kicking 50-, 60-yarders, left and right. One of them says ‘Weber, you’re good.’ Five or 10 balls in, I made the team.”

After his game-winning kick gave Arizona State the 1979 Territorial Cup and sealed a winning season — one that would culminate in a 16-10 Fiesta Bowl loss to Dan Marino and Pitt — Weber did not go on to lifelong riches and fame as a football player.

He played for Arizona for two more years, ending his career before his senior season. He finished his Wildcat career 47 for 52 on extra point attempts and 19 of 34 on field goals attempts.

There were highs — “Beating USC, coming home to the airport, that was insane,” he said — and lows.

“Being an athlete is sometimes not easy,” he said. “There were times I had pitfalls where I cried. You just have to figure out how to get through it. I want to point out — a year later, I remember missing three field goals. I remember what it was like to not have a second chance. I could sure enough tell you about my story of missing three field goals and losing a game and having little kids come up to me and say ‘Way to go, Weber.’ That’s part of life. It’s not defining.”

After the kick, Weber faded away just about as quickly as he starred.

“It didn’t change Brett a bit,” Holmes said. “He’s still the same guy today as he was right back then. A very positive, can-do type of guy. He stepped up and got it done. I still think to be honest with you, his shot from Sixth Street was just as good.”

• • •

The lasting takeaway from his story of second chances, Weber insists, is this:

“Would my life have been different had I missed the kick? If you really rely on sports to define who you are, I think that’s sad. I really do. I think you have to look at what your character is, what you’ve done as a person. We all have faults, but generally, when you wake up in the morning, do you feel good about yourself?”

Weber does. He’s older now, moving a little bit slower. But he’s happy, he’s healthy, and he’s thankful.

“Now when I wake up every day, I stand up, and I’m 6 feet above the ground, instead of six feet under,” he said. “I look at it as every day is a great day. I’ve had a couple second chances, do-overs, whatever the heck you want to call it. I’m having an enjoyable life. I try to treat people as well as I can. This isn’t destiny. It’s not that. I look at it as a second chance. A lot of people don’t get second chances in life. They make a mistake, and they have to have life with it and suck it up.

“I was fortunate to get a second chance.”

More than one, really.