PARADISE VALLEY — The year started with a roar for Dave Wood and his family.

The former Arizona Wildcats defensive tackle, third in school history in sacks, was playing in the celebrity pro-am at the 2015 Waste Management Phoenix Open. His tee shot on the par-3 16th hole at TPC Scottsdale — the PGA Tour’s party hole — landed on the green, bounced three times and plunged into the cup.

The crowd erupted. Wood raised his arms in triumph. He high-fived everyone in sight. Video of the hole-in-one has been viewed on YouTube more than 200,000 times.

More good times loomed. Dave’s sons, Carter and Trevor, were set to play together — and possibly start together in 2015 — for Arizona, following in the cleat prints of Dave and his younger brother, Brent. Carter was a senior center who made his first career start in the previous season’s Fiesta Bowl. Trevor, a sophomore, was the favorite to start at tight end.

“We were on such a roll. All our dreams were coming true,” Jan Wood, Dave’s wife, says. “Then we were just kind of blindsided.”

It wasn’t Carter’s career-ending foot injury during training camp that rocked the Wood family to its core. Nor was it Trevor’s season-ending shoulder injury.

It was something much, much worse.

Former University of Arizona defensive tackle David Wood talks about his cancer as his wife Jan listens in the background at their Paradise Valley home on Monday, April 11, 2016.

•••

They first suspected something was awry a little less than a year ago.

Dave was putting on weight. He seemed more tired than usual. But he had been traveling a lot for his job as a senior vice president for Outfront Media, the billboard company formerly run by Los Angeles Angels owner Arte Moreno, a Tucson native. Dave figured he was just getting older. (He turns 54 next month.) Jan was worried.

“She kept telling me, ‘Something’s not right. Go get checked,’” Dave says.

But you know how stubborn guys are sometimes, right? Dave had been an all-conference football player. He was indestructible. “Superman,” daughter Taylor affectionately calls him.

Dave still hiked three or four times a week at the Phoenix Mountains Preserve. He continued to work out. And his annual physical in August revealed nothing out of the ordinary.

So despite Carter’s and Trevor’s injuries, the Woods enjoyed the football season. The peak came at the end of the home schedule, when Arizona upset then-No. 10 Utah on Nov. 14. It was Carter’s senior night, and Dave and Jan came down from Paradise Valley for the weekend. They had a blast.

“We played golf. A bunch of buddies. A couple dinners. A good, long weekend,” Dave says.

But about 4 o’clock the morning after the game, Dave awoke in his hotel room at the Westin La Paloma Resort and Spa to excruciating pain. It “felt like somebody was stabbing me with knives throughout the abdomen,” he says.

The sensation lasted for about eight hours. Dave’s stomach had ballooned to the point that he appeared to be pregnant. He couldn’t ignore the symptoms any longer.

He saw his doctor that Monday morning. The doctor sent him to the hospital for tests. Fluid was drawn from his body with a cartoonishly large needle that looked like something out of a “Saturday Night Live” skit.

Dave learned soon after that he had a form of cancer no one in his family had ever heard of.

Former University of Arizona defensive tackle David Wood with wife Jan, center, daughter Taylor and son Carter at their Paradise Valley home on Monday, April 11, 2016. Wood has survived but continues to battle an aggressive form of cancer.

•••

Dave has pseudomyxoma peritonei, also known as PMP. PMP usually begins as a slow-growing tumor in the appendix. The tumor produces a jelly-like substance called mucin that can cause the appendix to swell or rupture, spreading cancerous cells inside the abdomen. Former ESPN anchor Stuart Scott died from appendiceal cancer in January 2015.

Although he had been experiencing discomfort and unusual symptoms — his stomach resembled a turtle shell — the diagnosis stunned Dave and his family.

“I didn’t believe it at first,” Trevor says. “You never believe it’s going to be you or anybody you know or anybody you love. It was a shock.

“But our whole family, we knew, if there’s one person that is going to get through this … it’s him.”

Dave Wood is a fighter. He’s the sort of person who doesn’t take no for an answer. The ordeal that was about to unfold would put his persistence to the test.

He was scheduled to undergo surgery the following Monday. But later that week, the surgeon told him he couldn’t do it. The procedure required was beyond his capabilities.

“At the moment, I was really pissed off at him,” Dave says.

In hindsight, however, it was the “best thing that could have happened, because I might not be here talking to you if he’d have proceeded with it,” Dave said earlier this week, sitting on the patio in the backyard of the immaculate five-bedroom home he shares with Jan, Taylor, Carter and their black Labrador, Duke.

“It’s very complex. They kept saying ‘rare.’ Rare was not a good word,” Dave said.

PMP affects about one in 500,000 people annually, according to the National Organization for Rare Disorders.

The Woods were referred to another, more experienced, surgeon at the Mayo Clinic in Phoenix. The new doctor scheduled surgery for about two weeks later, in mid-December.

First, though, he wanted to perform a laparoscopic procedure to determine the extent of the damage inside Dave’s body. It took about 2½ hours. Afterward, the second surgeon reached the same conclusion as the first: He couldn’t help him.

In lieu of surgery, the doctor offered the Woods a timeline: Dave had 6 to 12 months to live. The family was devastated. Dave was determined.

“As hard as that news was to hear … I just said, ‘That’s BS. I’m not accepting it,’ ” Dave says. “That was just kind of my mindset at that point. I’ve always told the kids forever, a half-assed effort or not doing your best is just not acceptable.”

Having twice been rejected, the family set out on a desperate search to find someone who could help Dave. They contacted friends. They talked to doctors. They reached out to cancer centers. They emailed Dave’s medical records. The most common response: “Sorry, we can’t help you.”

Finally, a friend came through. UA alum and donor Jeff A. Stevens, whose name adorns the Lowell-Stevens Football Facility, had some connections at the MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. A specialist there, Dr. Keith F. Fournier, agreed to meet with Dave and Jan.

They flew to Texas hopeful that Fournier would give Dave the one thing he wanted: a chance.

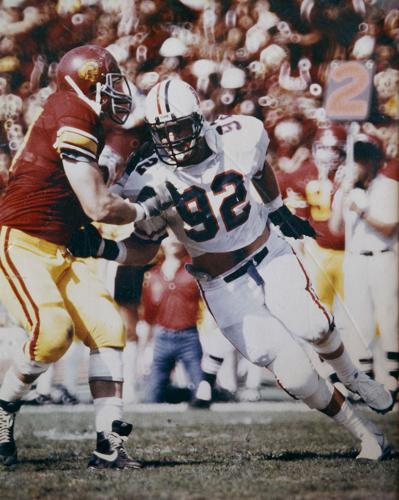

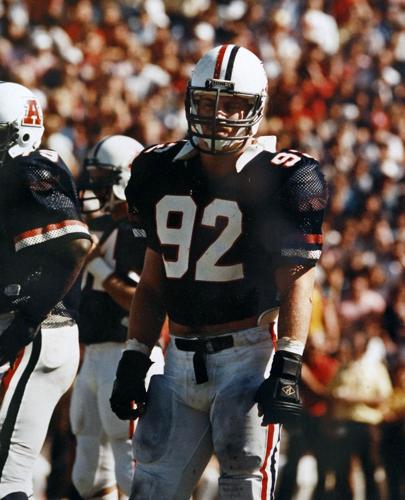

Dave Wood was an first-team all-conference defensive tackle for the Wildcats in 1984. He had 25 sacks in his UA career.

•••

Dave remembers being incredibly nervous while waiting in Fournier’s office.

“I’m just beading sweat,” Dave says. “Because if he comes in and says, ‘Hey, we can’t help you’ … we’ve run out of options.”

Dave describes himself as an impatient person. He wanted an answer. He got the one he was seeking: Fournier would at least give it a shot.

“I wanted to hug him,” Dave says. “I didn’t know him, but I felt like it. I told him thank you 50 times.”

Surgery was set for Jan. 4. It could last anywhere from 10 to 20 hours. If surgery was successful, Dave would be in the hospital for several weeks. The Woods rented an apartment near MD Anderson to make things easier for their kids and other visitors.

The family later learned that Fournier — after opening Dave’s abdomen — wasn’t sure whether to proceed. He considered sewing him back up.

“You never really know what you’re going to get until you get in there,” Fournier said by phone from Houston. “We weren’t sure we’d be able to help him.”

Instead, Fournier started digging. He ended up removing about 95 percent of the tumors. He also had to remove Dave’s appendix, his gallbladder, his spleen and part of his intestines. Between the initial surgery at the Mayo Clinic and this one, 14 liters of mucin were sucked out of Dave’s body.

At the end of his surgery, which lasted about 10 hours, Dave underwent hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy, or HIPEC. Also known as “hot chemo,” HIPEC entails filling the abdominal cavity with chemotherapy drugs heated to 107 degrees. Doctors and nurses swish it around for about 90 minutes.

Several of Fournier’s patients have compared the surgery and recovery to being hit by a Mack truck.

•••

Ten days later, the hospital discharged Dave, who retreated to the Houston apartment. He still had “tubes and all kinds of stuff going on,” he says, but he felt “really pretty good.”

It didn’t last. Two days later, he developed a 104-degree fever. He returned to MD Anderson, where he was diagnosed with an internal infection.

“With all that removal of organs and repositioning of things, I developed a leak in some of the intestines,” he says. “Basically, your body waste drains into your (abdominal) cavity, and it’s not good.”

Fournier couldn’t perform another surgery at that point because of what Dave already had gone through. The only way to eliminate the infection was for Dave’s insides to dry out — akin to a scab forming over a wound. In order for that to happen, he would have to fast for five to six weeks. His diet consisted of ice chips, the nutrients provided by IV bags — and one Popsicle per day.

“You have no idea how good one Popsicle can taste when that’s all you get,” Dave says. “It ends up being 5½ weeks of no food. That was probably one of the toughest things I’ve ever done.”

In many ways, this stretch was the hardest. Tubes were inserted into Dave’s midsection, feeding drainage bags. Dave is about 6 feet 5 inches tall, and his weight dropped from 250 to 185 pounds.

At one point, he felt something beyond exhaustion. Two-a-days in the summer heat of Tucson never left him so devoid of energy.

“There was nothing left in the tank,” he says. “That was the bottom.”

Fournier says extreme fatigue, lasting three to six months, is commonplace after the type of surgery Dave had — and the infection only exacerbated it.

“It was a pretty significant problem,” Fournier says. “Had he not turned the corner when he did, there was the potential to have to go back to the operating room.”

Fortunately, Dave did turn a corner. Back at MD Anderson, his IV nutrients were adjusted. As Jan wrote in her meticulous CaringBridge journal, “they put more calories in his ‘food bag.’ ” A hydration drip also helped.

Dave didn’t feel good. But he was starting to feel better. Over the next few weeks, his condition improved.

On March 1, Fournier removed one of the drains. A few days later, Dave started eating — chicken soup and chocolate chip cookies. A few days after that, Fournier removed the other drain.

On March 12, after almost three months in Houston, Dave and Jan went home.

Photo of former University of Arizona defensive tackle David Wood. Monday, April 11, 2016. Wood has survived but continues to battle an aggressive form of cancer.

•••

Dave has been back for a little over a month. He has come to appreciate the little things. His bed. His pillow. Food.

“I can’t tell you how good cottage cheese tasted,” he says.

He eats five or six times a day — “like every meal is the last meal,” he says. He has gained back 25 pounds. He exercises for about 30 minutes two to three times a day using pulleys and TRX bands to strengthen his core muscles. His bucket list is growing daily. He’s planning to return to work May 1 in a part-time capacity.

Fournier views all of these developments as promising signs.

“I never give patients too much data in terms of long-term outcomes,” he says. “But it’s certainly very hopeful. The early scans that we’ve done look quite good. He’s going back to work. That’s a pretty good prognostic indicator.”

Dave says he feels good, relatively speaking. His mind, he says, is “clear and fresh.” He says he’s about 50 percent to 60 percent of his old self physically. “But three weeks ago,” he notes, “I was at 10 percent.”

There have been several twists of fate during Dave’s trials and recovery, which he and his family consider a miracle. The surgeons who were in over their heads and turned him down. The friends who led him to Fournier. The critical adjustments to Dave’s hydration, nutrition and caloric intake.

But two factors made just as big a difference — maybe more.

Football scouts would classify them as “intangibles.” The first was the overwhelming support Dave and his family received from friends, friends of friends, acquaintances, UA alums and sports celebrities, including Herschel Walker, Shaquille O’Neal and J.J. Watt.

Dave’s CaringBridge page has been visited almost 14,000 times. Every journal entry has dozens of comments from well-wishers. When the family returned home for Christmas for a few days, Jan didn’t have to go to the grocery store because so much food had been delivered to their house.

“There’s been such a silver lining in our black cloud,” Jan says. “That’s what we keep saying. The people, the gestures. Everybody just took care of us.”

“Unbelievable,” Dave says. “Truly amazing.”

Those who know Dave Wood best describe him the same way. They cite his indomitable spirit, his positive outlook, his refusal to surrender. All of that matters.

“It’s hugely important,” Fournier says. “It’s a really difficult recovery. Folks who do the best are the ones who come in with the right attitude. You could tell up front: He had the attitude that he was going to get through this no matter what it took.”

Dave’s battle isn’t over. He has to return to Houston in July for a thorough follow-up exam. He’ll need one every four to six months for at least two years.

“My job in the meantime,” he says, “is to get physically and mentally strong again, build my body back up. That’s what I’m doing. And saying a prayer every night that it stays away.”