When the African American Museum of Southern Arizona opened its doors — or “cut the ribbon” — on Jan. 14 in the University of Arizona Student Union, co-founders Bob and Beverely Elliott hoped that 70 people would show up.

Then 362 people arrived.

“One guy even said, ‘This is like being at the post office around Christmas time; just take a number and wait,’” said Bob Ellliott, a former star basketball player at the UA.

Since then, nearly 40 schools and senior groups from across Arizona — including Phoenix, Flagstaff and Yuma — have signed up to tour the 1,100-square-foot museum dedicated to Black history, the first of its kind in Arizona.

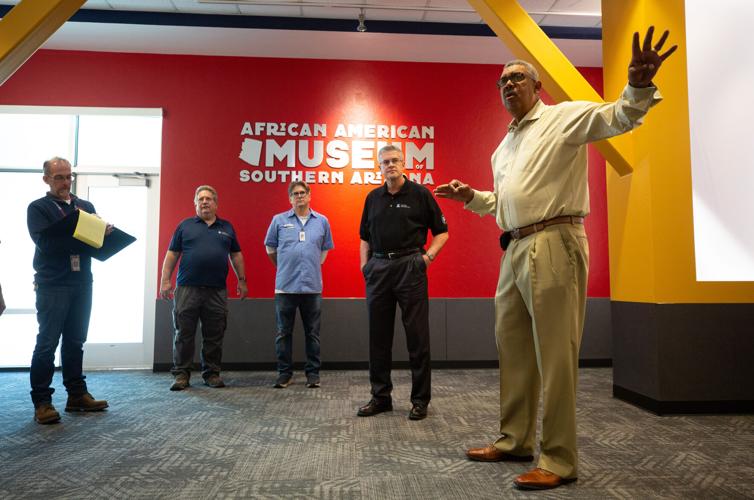

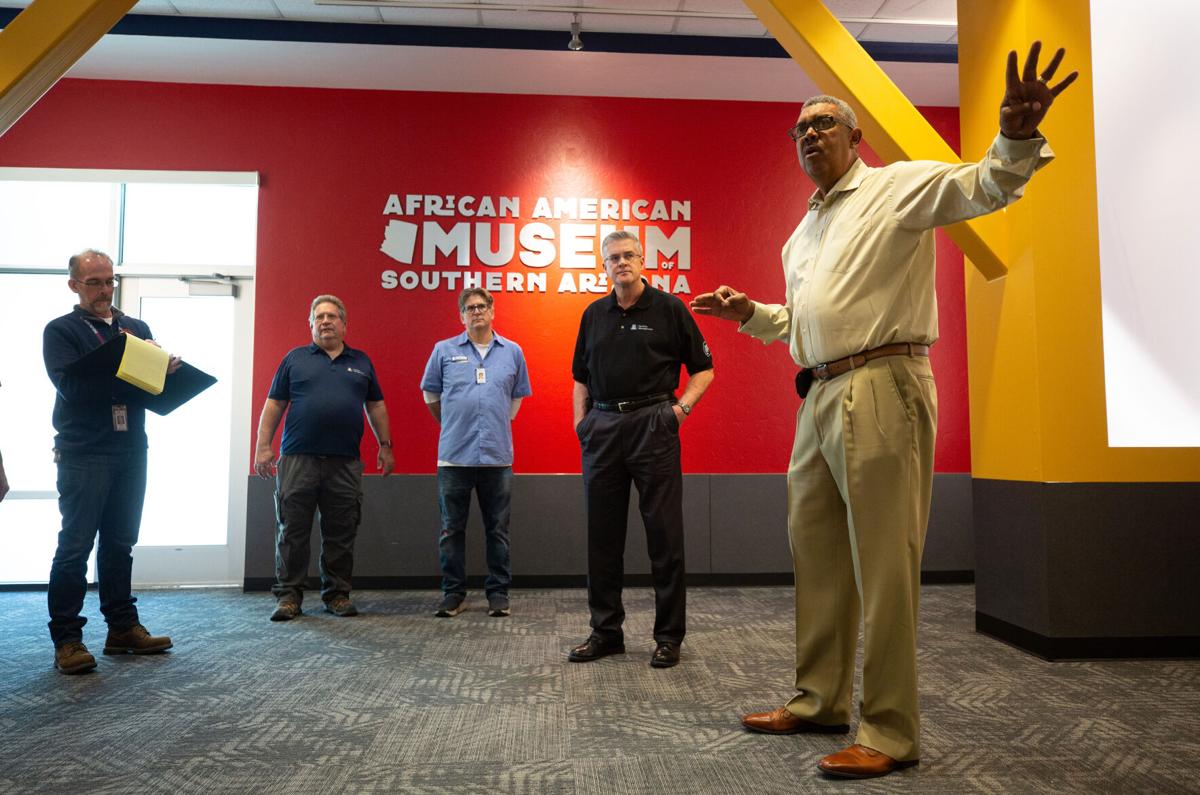

Beverely Elliott, one of the museum founders, talks about placement of historical paintings with UA facilities management staff at the African American Museum of Southern Arizona inside the University of Arizona Student Union on Oct. 28, 2022.

The inspiration behind the museum? A first-grader “doing the pandemic thing” and working on a virtual school project during Black History Month in 2021. Bob and Beverely Elliott’s 7-year-old grandson, Jody, now 9, was assigned to do a history report on a Black hero. Jody “overheard me talking to some friends about a museum I had been working with back in Michigan,” said Beverely, who calls herself “the family historian.”

Then Jody asked a question to his “Nanu” and “Big Poppa” — or “Big P, because he’s cool now.”

“He asked me about where there’s an African-American museum in Tucson or Arizona, and I had to think about it and realized I had not been to one,” Beverely Elliott said. “I had to tell Jody, ‘There’s not a museum in Arizona.’ Imagine hearing that at 7 years old. He was like, ‘Wait, what do you mean? Were there no Black people around or we didn’t do anything?’”

Jody’s response: “‘I think we should start a museum, and I’ll help.’”

It wasn’t just Jody. The Elliotts, both UA graduates and Michigan natives, received assistance from local philanthropists, collaborators and UA professors , including renown Africana studies associate professor Dr. Bryan Carter, who helped introduce holographic tour guides that can be accessed through QR codes at the museum.

Air Force Capt. Albert Randall poses in the cockpit of his F-4 Phantom while stationed at an airbase in northern Japan in 1969.

Local notables honored

Among the people honored at the museum is Air Force captain Albert Randall, a fighter pilot who learned to fly F-4 Phantoms at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base in 1969. On Randall’s uniform, he wore a patch with a Black Power fist over the confederate flag in protest of other pilots donning confederate flag patches.

When Randall’s commanding officer confronted him about the patch, Randall refused to take it off until the others did the same. Subsequently, only U.S. flags were allowed on pilots’ uniforms.

Air Force fighter pilot Albert Randall had this Black Power patch made in response to other airman in his unit who wore Confederate flag patches on their sleeves. Randall said his quiet protest in 1969 prompted new rules prohibiting U.S. servicemembers from wearing any flag besides the American one.

“We gotta get these stories out that people don’t know about, and that’s what the museum is all about,” Bob Elliott said.

Elliott’s head coach at the UA, Fred “The Fox” Snowden, has multiple displays inside the museum.

“If Coach Snowden and (athletic director) Dave Strack don’t convince me to come out here, you and I are not having this conversation right now, because Tucson, Arizona was not on my map out of the 300-something schools to go to,” Elliott said.

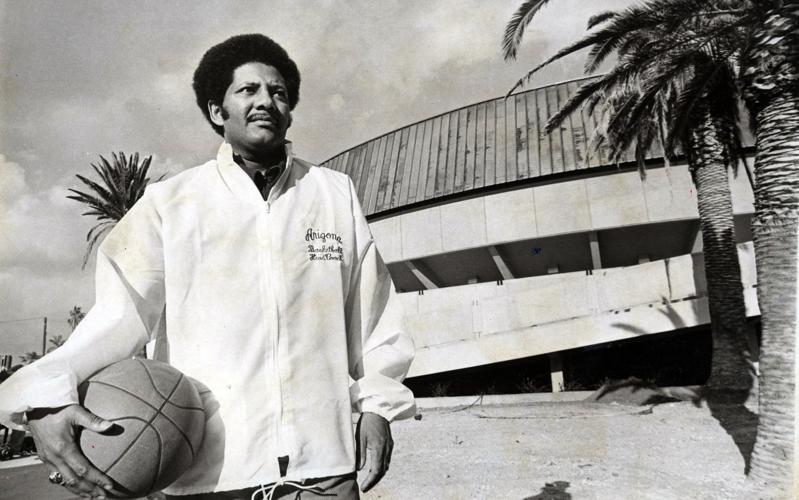

UA head coach Fred Snowden surrounded by players during University of Arizona basketball vs. Arizona State at McKale Center in Tucson on Mar. 6, 1976.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of Arizona hiring Snowden — and McKale Center opening to the public. Snowden, who went 167-108 in 10 seasons and led the Wildcats to the 1976 Elite Eight, is the first Black head coach at a major university.

“We tell our grandkids, ‘There’s only one first.’ Coach Snowden is the first Black head coach at a major university, and it unlocked the door for all these other coaches and institutions to feel comfortable hiring a Black man to lead their program,” Bob Elliott said.

Since Snowden, the Wildcats have hired Black head coaches to command their women’s basketball (Adia Barnes), football (Kevin Sumlin), track and field (Fred Harvey), cross country (Bernard Lagat) and gymnastics (John Court) programs. Most recently, Charita Stubbs became the first Black head coach of the Arizona volleyball program, replacing longtime leader Dave Rubio.

Fred Snowden, the first Black basketball head coach in Division I, went 167-108 in his 10 years at Arizona.

“I know our volleyball program is in great hands with a coach who is qualified, put in the work and got the opportunity. That’s inclusion,” said Arizona assistant football coach and former administrator Scottie Graham. “Just give us the same opportunity. When I say ‘us,’ I mean people that are different from other people in power.”

Snowden’s daughter, Stacey Snowden, was a panelist for a recent fireside chat at The Loft Cinema to talk about her father’s legacy.

Current Arizona head coach Tommy Lloyd “was in row two, with some popcorn, soaking up every story.” One of Lloyd’s assistant coaches, Steve Robinson, a former head coach at Tulsa and Florida State, rushed to find Stacey Snowden after the discussion.

“He was so thankful for what Coach (Snowden) did to unlock the door for him to become a head coach, which he was,” Bob Elliott said. “It was really touching.”

Another notable fireside chat featured Ruby Bridges, the first Black child integrated in a former all-White elementary school in Louisiana in 1960. She’s the subject of Norman Rockwell’s famous “The Problem We All Live With” painting.

U.S. Deputy Marshals escort 6-year-old Ruby Bridges from William Frantz Elementary School in New Orleans in November 1960.

“She was a 6-year-old from New Orleans. She said when she saw the crowd and people throwing things, she thought, ‘Oh, this must be another Mardi Gras.’ Then she realized they were throwing rotten tomatoes and eggs,” Elliott said. “The story was so moving. … Originally, our tagline for the museum was that we wanted people to leave and say, ‘I didn’t know that.’

“After the Ruby Bridges fireside chat, we said, ‘We are a movement, not just a museum.’ We want to bring people to Tucson and educate our community about life as a Black American. … Education, knowledge, experiences, it all goes together.”

Civil rights icon Ruby Bridges and University of Arizona basketball legend Bob Elliott greet a crowd at Palo Verde High School during a fire-side chat event.

UA student-athletes among first visitors

Educating student-athletes on Black history has been among the top priorities of the UA football regime under head coach Jedd Fisch. Every Arizona player and staffer visited the museum once it opened.

“Since we’ve been here, … we’re a school of inclusion. It’s obvious,” said Graham, Arizona’s running backs coach who earned a master’s degree in Black studies at Ohio State University. “When we first came here, we did something every week on Black History Month, so it’s really exciting for the young guys to just understand what Bob Marley’s ‘Buffalo Soldier’ brought to America. … They have to understand it wasn’t just a song, it was about a person existing and he fought in wars.”

In the limited time Graham is able to meet with his running backs in February, he preaches “constant education and being lifelong learners.”

“‘Who invented the elevator? Who invented peanut butter?’ Just to give them that kind of education on Black History Month,” Graham said. “But, really, for me, it’s about Black History Month and it’s about living your life every single day.”

Graham also informs his students — err, running backs — about influential Black figures in football history, such as Gene Upshaw, the former executive director of the National Football League Players’ Association who helped increase pay for Black players, who were paid far less than their white teammates.

Arizona Running Backs Coach Scottie Graham, right, talks to wide receiver Sam Graci-Glazer (83) during Arizona Football’s fall training practice at Arizona’s Dick Tomey Football Practice Field in Tucson, Ariz. on Aug. 8, 2022.

Graham’s message to his players: “‘Remember, when Gene took over the NFLPA, players were making 30%. When Gene died, the players were making 70. And it was someone who looked just like your granddaddy who did that. It just doesn’t fall from the sky, it was a battle.’”

Graham said the UA football team’s tour of the African American Museum of Southern Arizona was exciting.

“I know they want to grow the space, so it’s great for me being a young African-American coach at a school where it’s not just talked about. We get invited to the dance and get a chance to sit down — and we offer you an appetizer,” he said. “Inclusion is nothing until you invite the person in. To invite them is great.”

Added Graham: “To see a husband and wife be in a position to curate and to carry history and to start somewhere is important. They’re growing it and maximizing it, and to see the passion behind it is incredible to me.”

Bob Elliott and the 1976 Arizona Wildcats posted what was, at that point, one of the greatest seasons in program history.

Elliott believes the museum will help attract more minorities to either attend or work at the UA.

“Let’s be real: One of the problems we’ve had at the University of Arizona is the retention and recruiting of African-American students, faculty and staff, and I think this will be a great resource for the university all across campus,” Elliott said. “And it’s already started.”

Beverely Elliott, one of the museum founders, thanks UA Facilities Management staff at the African American Museum of Southern Arizona inside the University of Arizona Student Union on Oct. 28, 2022.

“It’s not just the museum I’ve always wanted,” Beverely Elliott said.

“It’s the museum the community needed.”