The University of Arizona is making changes in the wake of a firestorm of court filings involving sexual harassment and domestic violence issues in the athletic department.

Starting this week, an attorney who specializes in gender discrimination law will lead a comprehensive review of the university’s processes and policies and also examine how the UA coordinates with supporting agencies such as law enforcement and health care.

“There is no place for sexual misconduct and discrimination at the University of Arizona and we’re working to ensure that a positive and supportive culture reaches across the entire university,” UA president Robert C. Robbins wrote Friday in an email to the Star. “I’m committed to investing in the people and resources needed to place our prevention, support and response measures among the very best in the country. Our students, employees and the university community deserve no less.”

The UA has hired Title IX attorney Natasha Baker to guide a review of its processes and policies. Baker, who starts this week, works at the San Francisco law firm Hirschfeld Kraemer and trains campus administrators about Title IX compliance and campus investigations.

Baker was hired in early February. Days later, Robbins sent an email to faculty, students and staff that said sexual misconduct and discrimination “will not be tolerated.”

“While we cannot guarantee that the incidents will not happen here, it is a top priority for us to do all we can within our roles as educators and employers to prevent them,” he wrote.

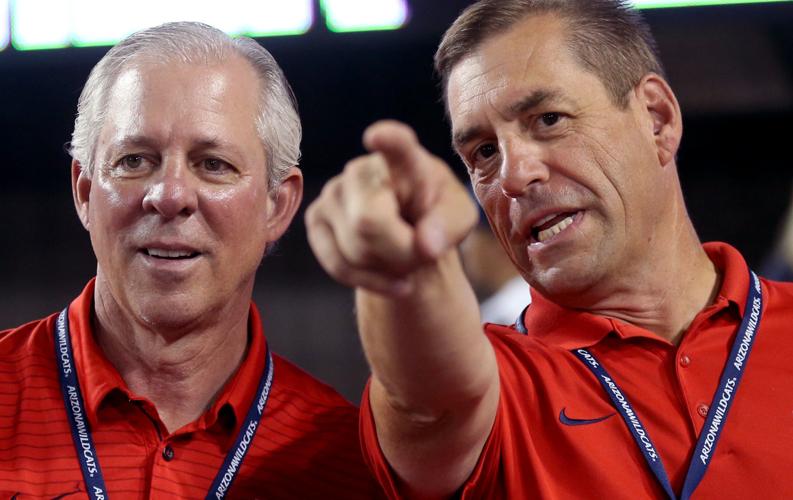

UA president Robert C. Robbins, left, and athletic director Dave Heeke say were proactive in placing the Wildcats on a self-imposed postseason ban in the 2020-21 season.

Robbins’ February email emphasized that the university is no different from colleges and universities across the country that are also “wrestling with reports of sexual assault, relationship violence, sexual harassment and discrimination.”

The UA has more than a dozen offices that provide education, counseling, health care, investigative and other support services related to Title IX, a federal law that protects students from gender discrimination. While the quantity of those services demonstrates the school’s commitment to students, they will be better served by “gathering our existing resources in a more coordinated and enhanced fashion,” Robbins wrote.

Details of Baker’s contract with the school weren’t immediately available and UA spokesman Chris Sigurdson said he didn’t know how long her review would take. Baker did not respond to the Star’s request for comment.

The UA is defending itself in two federal lawsuits and one local civil lawsuit, all of which claim the school failed to protect students from dangerous men on campus.

In 2015, assistant track coach Craig Carter was arrested after reportedly threatening an athlete with a box cutter while his other hand was wrapped around her throat. After the incident, Carter sent dozens of text messages and emails to the woman, threatening her and her family members, Pima County Superior Court documents say. The woman is suing the UA in Pima County Superior Court for not protecting her. Carter and the student-athlete were engaged in a sexual relationship that the coach says was consensual.

In 2016, running back Orlando Bradford was arrested and charged in connection with choking two ex-girlfriends. A third woman told campus police that Bradford had choked her, but hasn’t filed a claim or sued. Bradford is serving five years in prison.

Orlando Bradford, a former Arizona Wildcats football player, will serve five years in prison for two felony counts of aggravated assault. Two of his victims are suing the UA in federal court.

The two victims have sued the UA in federal court and one of the suits has since been amended to include allegations of gang rapes by football players. No details were provided in the claim, and it’s unclear if anyone has been charged.

Legal troubles involving coaches and athletes extend beyond the suits against the university.

Football coach Rich Rodriguez was fired Jan. 2, the same day a sexual harassment and hostile workplace claim against him became public. The notice of claim, filed by Rodriguez’s former assistant, says the coach fostered an environment where Title IX “did not exist.”

In 2016, the university issued UA basketball player Elliott Pitts a one-year suspension for sexual misconduct related to the alleged sexual assault of a fellow student.

Addressing ‘toxic masculinity’

Sexual violence perpetrated by athletes is sadly common on college campuses, one expert said.

“The problems of sexual assault, sexual violence and sexual abuse are so ubiquitous,” said Mitch Abrams, a psychologist who specializes in anger management and violence in sports. “It’s happening everywhere.”

Training is part of the problem, Abrams said — many schools are using outdated or ineffective models to teach violence-prevention to athletes.

Mitch Abrams

“People want to pretend that they’re doing something about it. What’s been done, in my opinion, is the equivalence of putting a Band-Aid on a gaping wound,” Abrams said.

He says bystander intervention training, such as Arizona’s Step UP! program, is ineffective and difficult to implement. Step UP! teaches students how to be proactive in helping others in situations involving alcohol, dating violence, gambling, hazing and depression.

“If these programs work, then why isn’t the problem ameliorating?” Abrams said. “Bystander intervention as a primary approach is deliberate indifference.”

Arizona officials learned that first-hand in the Bradford case. Tucson police reports show that four of his roommates — all UA football players — routinely witnessed him abuse women, but failed to intervene on all but one occasion. All four teammates, and Bradford, had been trained in the Step UP! program.

Rather than teach bystander intervention, Abrams said, schools must address what he calls “toxic masculinity” and increase accountability among their athletes.

Some athletes and coaches “believe they have different types of rules,” Abrams said. “When we hold coaches and athletes up like that, we can’t be surprised when they take liberties.”

Toxic masculinity plays a key role in violence against women, in that low self-esteem in men causes them to use physical power to regain control, Abrams said.

“These people can change, but they need treatment,” Abrams said, adding that schools often expel players when they recognize a problem, rather than offering help. “If we don’t treat people, we aren’t reducing the number of victims.”

He said that when schools learn athletes or coaches are violent toward women, many cover it up or kick them out — often depending on how valuable the player or coach is to their program.

When UA officials learned of the situation involving Carter, they quickly took action and fired him, even banning him from campus. Carter coached a sport that receives little national attention and doesn’t generate revenue.

Craig Carter

Bradford, a potential starter for one of the UA’s two showcase programs, seemingly received more slack. Police reports show school officials were made aware of his violent tendencies nearly a year before his dismissal.

Abrams said sweeping changes are necessary to fix the problem. Without trying to understand how perpetrators think, it’s impossible to reduce the incidents of violence by athletes.

“It’s pennywise and pound foolish. Schools are prioritizing things to save their reputations but not addressing the long-term solution,” Abrams said. “I think people would rather pretend they’re doing something about it rather than saying, ‘I really don’t know and I need to bring in people who do.’”

Admitting and addressing the problem is smart fiscally as well as morally, Abrams said.

“Risk management is cheaper than damage control,” he said.

To protect and serve?

The University of Arizona Police Department factored prominently in both the Bradford and Pitts cases.

One of Bradford’s girlfriends called campus police in early 2016 to say he’d been pounding on the door to her dorm the night before, trying to get in. She told UA police officers during an interview that he had choked her in the past.

Instead of arresting Bradford, as Tucson police did six months later when another woman came forward to say he’d choked her, campus police chalked up the incident to a tumultuous relationship between students, and closed the case. Bradford was moved off campus to a house with other football players.

Campus police were also the first to respond when, in late 2015, a student called to say he believed his sister had been raped at an off-campus apartment by Pitts. Police officers woke the woman and interviewed her while she was half-asleep and still intoxicated, during which she denied having sex at all. Campus police eventually called the Tucson Police Department, since the assault took place off campus.

Pitts was not charged with a crime, and prosecutors later told the Star that the body camera footage from the interview “would have been Defense Exhibit Number One” had the case gone to court.

Arizona’s Elliott Pitts reacts during the first half in a regional final NCAA college basketball tournament game against Wisconsin, Saturday, March 29, 2014, in Anaheim, Calif.

Abrams said that every campus should use outside police officers trained to investigate all claims of sexual violence or domestic assault. Officers who are paid by the college have an inherent conflict of interest, especially when the students involved are athletes, he said.

Many colleges and universities outsource serious criminal investigations to city or county police in order to get the most experienced detectives looking into the allegations. The UA does not.

Campus police departments are often better funded, better educated and better trained than their city and county counterparts. More than 60 campus cops patrol the UA’s 392 acres; UAPD is certified by the Commission on Accreditation for Law Enforcement Agencies, a private law force accreditation agency.

However, campus police’s experience with serious crimes is often lacking. In 2016, UAPD officers investigated 704 liquor law violations, 108 drug law violations, 21 domestic/dating violence cases — and 13 rapes.

“There’s a very important role for campus police agencies to play,” said Seth Stoughton, an assistant professor at the University of South Carolina School of Law and a former Tallahassee, Florida, police officer. “And it’s not to investigate very serious crimes.”

Getting the house in order

Arizona’s football program has been at the center of the recent litigation involving Bradford’s accusers and claims that Rodriguez created an environment that was unwelcoming and even dangerous to women.

Rodriguez told the Star in an email that Title IX is important to him.

Rich Rodriguez was fired the same day a sexual harassment and hostile workplace claim against him came to light. He said the claims by his former assistant aren’t true.

“Title IX has been a vital and revolutionary legislation for over 45 years,” he wrote. “As reiterated in our recent filing with the Attorney General’s office, I have always, and will continue to instruct my staff and athletes to be inclusive, respectful and adherent to Title IX polices.”

New football coach Kevin Sumlin says he has always taught his players to treat women with respect. Before Arizona, Sumlin was the head coach at Texas A&M and Houston.

“It goes without saying, we’ve demonstrated that culture the last two places I’ve been,” Sumlin said, adding that he hasn’t yet had the opportunity to do Title IX training with his players. “Over the course of time in the spring, when we have more time to meet and do some other things with them, we’ll take advantage of that with Title IX education, team and university-conduct rules.”

The school and athletic department have seen a change in leadership in the past year, with Robbins taking over as UA president and Dave Heeke now at the helm as athletic director. Former UA athletic director Greg Byrne, the man who hired Rodriguez and was in charge during the Carter arrest, Bradford arrest and Pitts incident, has denied Star interview requests, citing the pending litigation.

The president and athletic director’s status as outsiders may help them, said Bill Ridenour, chairman of the Arizona Board of Regent.

Robbins and Heeke are “able to take a fresh look at everything, because that’s necessary here,” he said.

Bill Ridenour

Chairman of Board of Regents

Ridenour, an attorney, has led the Regents to reevaluate the way they structure coaches’ contracts. Deals signed by Sumlin and new ASU football coach Herm Edwards include a larger “for cause” category that would give the universities some protections if campus rules, NCAA bylaws or criminal statutes are broken.

An internal investigation into the allegations against Rodriguez did not find enough evidence to fire him for cause. As a result, Rodriguez was given a contract buyout of about $6 million. Former ASU coach Todd Graham got $11 million.

Ridenour, a UA grad, said he’s concerned about the university’s reputation, which he considers paramount to anything the athletic department does.

“As a Wildcat, I want to make sure that we get our house in order,” Ridenour said. “I think we’re doing that.”