Vern Friedli sent his résumé to the Amphitheater School District in the spring of 1976, a few months after the Panthers went 12-1 and won the state championship.

If he was intimidated, it didn’t show. Out of his league? He wasn’t hearing it.

All Friedli wanted was an interview, because his coaching résumé wasn’t going to turn anybody’s head:

Baseball and football coach at Sunnyside Junior High, 1961-65. Football and baseball coach at Morenci High School, 1964-74. A year each as head football coach at Casa Grande High School and San Manuel High School.

Records? He didn’t crack .500 those last two seasons.

Amphi whittled its list to seven men, including Jake Rowden, the top assistant on the school’s ’75 championship team and former defensive coordinator at Arizona. The Panthers were looking for a heavyweight, and the 5-foot-8-inch, 145-pound Friedli, a theater arts major from Humboldt State who had done a two-year shift in the Army at Fort Huachuca, weighed in and gave it his best shot.

Perhaps the most impressive thing he could’ve put on that résumé was that he married Amphi grad Sharon Rose Falshaw in 1957, and that as a teenager Sharon had spent time as a dancer on national television shows.

“I don’t know what they saw in me,” Friedli said at his 50th wedding anniversary celebration one December night at Starr Pass in 2007. “But I told them they wouldn’t be sorry.”

When he was 74, still wearing that ubiquitous green cap with a big A on it, Friedli’s Panthers went 11-2. The shrinking school district was such that Friedli’s 2010 team had 28 players on the varsity. By then his teams had won 328 games, a state record.

“I don’t see why I can’t do this another 10 years,” he said. If anyone was going to coach until he was 84, it was Vern Friedli.

A few months later, I saw Sharon Friedli’s name on my ringing telephone. I dreaded answering.

“Vern had a stroke in the weight room,” she said. “He had been lying on the floor for a few hours before I found him.”

Three months later, February 12, 2011, the phone again lit up with Sharon’s name. She was driving Vern home from the school.

“He’s got something to tell you,” she said, handing him the phone.

“I resigned today,” he said.

He handed the phone back to Sharon.

That was Vern Friedli. He got to the point. There was precious little chitchat.

For the next six years, Vern Friedli battled fiercely to overcome a series of strokes. I saw him in April at the College Football Hall of Fame banquet at the DoubleTree Hotel. He was sitting in a wheelchair and had difficulty holding a conversation.

I remember thinking of the irony. The man in the wheelchair, Vern Friedli, was the toughest guy in a room full of football players.

When he died at 4:22 a.m. Friday, two months shy of his 81st birthday, I suspect Friedli’s arrival at the gates of heaven was similarly short of words. His 331 career victories meant nothing. He was a tough sonofagun, a man of principles, a coach who exhorted his 36 Amphi Panther teams to “make your mother proud.”

And it had nothing to do with football.

It had everything to do with being a good man.

Friedli coached Super Bowl champions like USC’s Riki Ellison, Olympic medalists like Arizona’s Michael Bates and 1,000-yard rushers like Stanford’s Jon Volpe. But mostly he coached undersized minority kids without an extra quarter to spend.

His Panthers teams might’ve won six or seven state championships had he given in to the state’s reclassification system, and “played down” in Class 4A or 3A or whatever. He chose to get in the ring with the best.

“He was a tough coach. He was trying to prepare his players for the mental toughness and discipline needed to be successful as a parent, a husband and occupations,” Ironwood Ridge state championship coach Matt Johnson, a 1990s Panther lineman, said Friday. “He would challenge players but never to break their spirit. He wanted to drive them to answer the challenge, to prove to themselves that they could get the job done under pressure.”

It didn’t take long for Amphi to understand it had hired the right coach.

Friedli won his first game as a Panther on Sept. 24, 1976, stunning No. 6 Sahuaro on a last-second field goal, 17-15. It was a game that came to define the way he would coach for the next 36 years.

“We basically didn’t have a quarterback, so two days before the game he told me I was going to get some reps at quarterback,” said Steve Doolittle, who went on to be a standout receiver/linebacker at Colorado and a Buffalo Bills draft pick.

Sahuaro scored to take a 15-14 lead with 58 seconds remaining. Amphi, the team without at QB, Friedli’s first Panther team, appeared to be cooked.

Doolittle sat in a Campbell Avenue restaurant last November, telling the story of the final 58 seconds against Sahuaro. He would shake his head, as if to say, “I still can’t believe it.”

“We completed one pass in the game — our last pass of the game and my first pass ever,” Doolittle said with a smile. “We hung in there with toughness and the pledge not to quit. On the final play of the game, we kicked a field goal to win it. Sahuaro was the ‘it’ team then. After that, I thought anything was possible.”

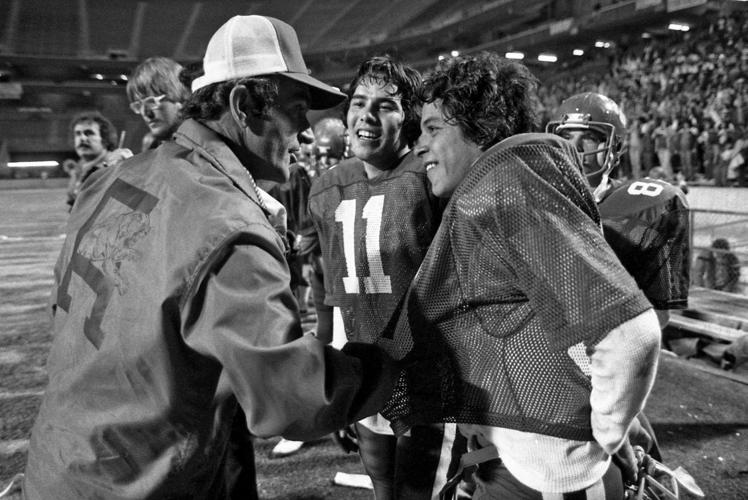

Three years later, Friedli’s Panthers went 13-0 and won the last big-schools state football championship in Tucson history.

The son of a Northern California lumber mill operator cut down the biggest trees.