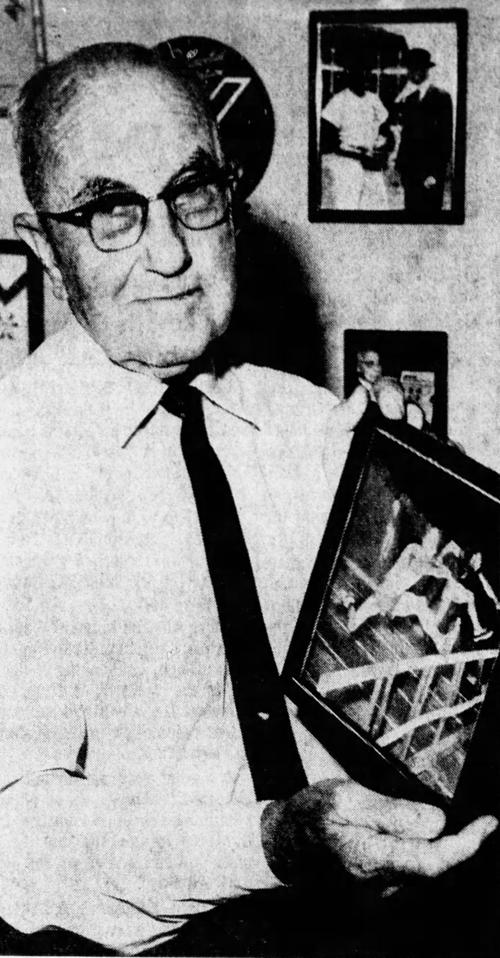

Doc Van Horne didn’t have many of those days when little went right. He coached Tucson High School to 13 state track and field championships from 1927-53, producing Arizona’s track athlete of the year eight times: Joe Batiste (twice), Frank Batiste (twice), Fred Batiste (twice), Willie Brown and Bill Gaston.

But in April 1942, James Don “Doc” Van Horne of Mansour, Iowa, had one of those dark days that changed his life.

While Van Horne’s Badgers athletes were working out at the school’s track facility, someone stumbled while throwing the javelin. Van Horne heard someone shout “LOOK OUT!”

The javelin hit senior Mike Clarke, piercing his shoulder. Van Horne rushed to Clarke’s aid. Someone phoned the police department. Fortunately, Clarke survived without permanent injury, but the frightening incident led to change.

The Arizona Interscholastic Association banned the javelin throw from state competition for the next 50 years. And Van Horne, a chemistry teacher when not coaching track, decided there was more to life than coaching a track team — even one that had easily won state championships in 1938, 1939, 1940 and 1941.

After the '42 state finals, Van Horne, 49, resigned his coaching and teaching positions at THS and enlisted in the Marine Corps. He was assigned the rank of sergeant and made the chief Marines recruiter in Southern Arizona.

After World War II ended, Van Horne returned to Tucson High. His teams then won five more consecutive state championships from 1945-49. He retired from coaching and teaching in 1953 (when the Badgers again won the state track title) and subsequently became the first athletic director at Pueblo High School.

When he spoke at a year-end banquet honoring his career achievements in 1953, Van Horne was asked which of all his state championship teams was best.

“Without a doubt, the ‘39 team,” he said. “It’s the best team we’ve ever had.”

That “best team we’ve ever had” almost was derailed before it got on track to a runaway victory at Arizona Stadium in May 1953.

In the winter of ‘38-39, acting on a tip from an unidentified source, the AIA suspended Joe Batiste, declaring that he was too old to compete in high school sports. An investigation into Batiste’s age followed, but his parents, Ernest and Loretta Batiste, said they did not have a birth certificate.

They said Joe — who had set the national high school record in the 110 high hurdles at 14.5 seconds — was born in Lake Charles, Louisiana, in 1921 but could offer no proof. The AIA concluded there was no known birth certificate for Batiste, and about a month before the state championships, ruled Batiste eligible.

The Star described the 1939 state meet as “the greatest track and field carnival in our sovereign state’s history.” It further described Batiste, favored in the 120 high hurdles, high jump and long jump, as having “the speed of a greyhound and the spring of a kangaroo.”

The Arizona Interscholastic Association's decision to rule Joe Batiste eligible was front-page news in the May 5, 1939, edition of the Star.

Batiste re-set the U.S. record in the 120 hurdles, blazing to a 14.0-seconds finish — a state record that would stand until 1962. Batiste won by 10 yards, which was unthinkable.

The all-Black 4x200 relay team of Batiste, Garfield Johnson, Jesse Higgins and Fred Foley easily won the state title. Higgins also won the 100-yard dash. Van Horne referred to his champions as “the all-conquering Badgers.”

Batiste appeared to be bound for the USA 1940 Olympic team as America’s leading hurdler. But World War II ended both the 1940 and 1944 Olympics. Batiste was drafted into the Army and later found that enrolling at Arizona was not as simple as competing for Tucson High School.

Despite Van Horne’s attempts to get Arizona to accept Batiste’s application for enrollment, the UA declined. Batiste instead spent two ordinary years at ASU, but his athletic dominance of the late 1930s ebbed. He was no longer a standout athlete.

“Van Horne gave (Black) athletes their first opportunity in Tucson athletics,” Star columnist Abe Chanin wrote. Not only did Batiste and his younger brothers Fred and Frank become the state’s track and field athletes of the year in 1940, ‘41, ‘43 and ‘44, but Higgins, Ellis Webb and O’Dell Gunter — all Black — became state champions.

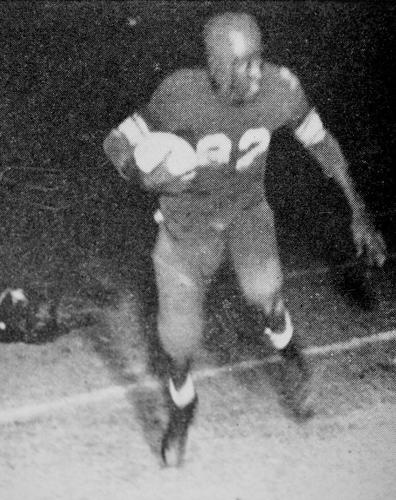

Fred Batiste became the first Black athlete to earn a letter in UA history, a two-way starter for the 1949 Wildcat football team. He was elected to the UA Sports Hall of Fame last month; he will be inducted in September.

Fred Batiste was a football and track star at Tucson High who went on to play running back at the UA.

After leaving his administrative roles at Pueblo, Van Horne retired in 1959. He wasn’t forgotten. The TUSD subsequently named a new school on East Pima Street Van Horne Elementary. It closed in 2011.

Van Horne died in 1986 while visiting his son in Amsterdam. He was a charter member of the Arizona Coaches Hall of Fame in 1992.