No one in the Arizona men’s basketball Ring of Honor has a résumé like Kenny Lofton’s.

It’s unlikely we’ll ever see another who follows his path.

Michael Lev is a senior writer/columnist for the Arizona Daily Star, Tucson.com and The Wildcaster.

Lofton, whose banner was unfurled at halftime of Arizona’s 103-83 victory over Oregon on Saturday at McKale Center, played four seasons with the UA hoops squad. He finished his career as the program’s all-time leader in steals and helped the Wildcats reach their first Final Four in 1988.

His qualification for the Ring of Honor? A 17-year career in Major League Baseball.

Lofton barely played baseball at Arizona. His name appears two times in the UA baseball media guide — under “Arizona MLB players” and “MLB Draft history.” It is believed that Lofton had one official at-bat. Most of his action on the diamond came with Arizona’s junior varsity team, which is a thing that no longer exists.

Clark Crist, a scout for the Houston Astros who started at shortstop for Arizona’s 1980 national championship team, heard that the dynamic point guard was working out with the UA baseball team. Crist went to check him out and instantly recognized Lofton’s elite athleticism. Crist persuaded the Astros to draft him in 1988. It was a complete projection.

Former Arizona basketball player Kenny Lofton, a longtime Major League Baseball player after his days as a Wildcat, speaks with media before having his name raised in the UA men’s basketball Ring of Honor at McKale Center Saturday.

“We didn’t have any stats,” Crist said Saturday after Lofton’s pregame news conference Saturday. “Today, what would they have done with Kenny Lofton? They’d have no idea because they wouldn’t have any numbers on him. You have to dream.”

It’s hard to imagine something like that happening today because it probably wouldn’t. For better or worse — and there’s empirical evidence to suggest it’s worse — we’re in the age of specialization. More and more young athletes are playing the same sport year-round. For scholarship-caliber athletes, participation in camps and showcases provides exposure to coaches and scouts. Those performances boost their ratings.

But does it truly make them better ballplayers?

Lofton insists that the skills he developed on the basketball court helped him become a better center fielder. He won four Gold Gloves.

“Basketball had a lot to do with that,” Lofton said. “If I didn’t have the basketball ability I had, I don’t know if I would have been able to understand getting up over the wall and make it look so easy as I did.”

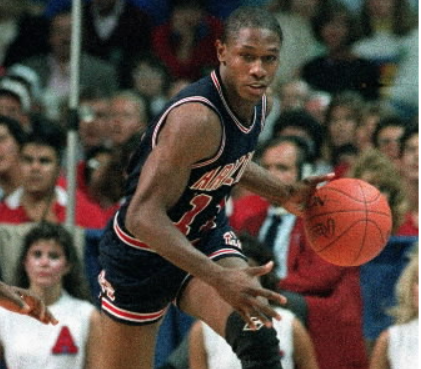

Arizona's Kenny Lofton dribbles during a Final Four game against Oklahoma in 1988.

Watching his basketball highlight reel on the video board Saturday, you could picture it. Lofton could dunk with ease. In one clip, he did a double-pump reverse jam. Of course he could scale the wall to rob home runs.

I have yet to meet a college or professional coach who didn’t value multisport participation. They universally view it as a positive.

“We talk to recruits every day,” said UA baseball coach Chip Hale, who was a standout quarterback in high school. “One of the first questions we ask is, ‘Do you play any other sports?’ Most of the time now they don’t ... unfortunately.”

If you play another sport besides baseball, Perfect Game might view you as imperfect. If you play another sport besides football, you could be a three-star prospect instead of a four-star.

“Let me tell you something: Good athletes play other sports,” said Crist, who’s now retired and living in Phoenix after scouting for the MLB club for 30 years. “When people are driving you just to play one sport, if you look at the travel ball and all that, it’s all money. You have to pay for that kid to play there. They don’t want that kid to leave because they make a salary off that kid.

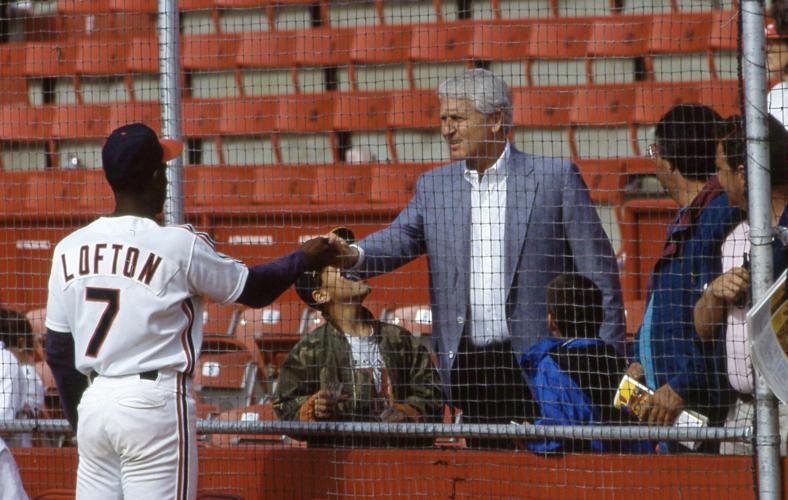

Former University of Arizona basketball player Kenny Lofton, left, greets UA coach Lute Olson at a Cleveland Indians baseball spring training game at Hi Corbett Field in Tucson on March 31, 1992.

“They tell (families), ‘Look, if you go play basketball, Johnny over here, who’s full time with us, he’s going right past you.’ That’s a bunch of baloney.”

Lofton played baseball and basketball at Washington High School in East Chicago, Indiana. He elected to play basketball in college for financial reasons: He could get a full scholarship as opposed to a partial one for baseball.

Lofton excelled on the court at Arizona, but he missed baseball. He asked if he could work out with the team. He also figured he could be a more impactful player on the diamond.

“I knew this was my path after the Final Four,” Lofton said as he reeled off the names of his more celebrated and higher-scoring teammates. “I wasn’t going to get no shots off.”

Crist learned through a family friend that Lofton was dabbling in baseball again. His speed was undeniable. He was also rusty and raw and had a hitch in his swing.

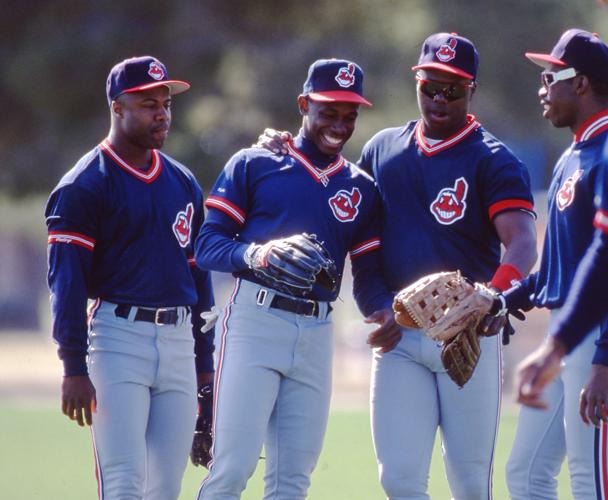

Former UA basketball player Kenny Lofton, second from left, gets some friendly ribbing from his new teammates on the Cleveland Indians during spring training at Hi Corbett Field in Tucson in 1992.

But Crist liked that Lofton was a left-handed batter, and he believed in betting on athleticism. Crist also came to learn that the best athletes pick things up quicker than most.

The Astros selected Lofton in the 17th round of the ’88 draft — “The worst 17 rounds of my life,” Crist said, “because all I could imagine is if I lost this kid” — and he played minor-league baseball in the summer between his junior and senior years at Arizona.

Lofton made it to the majors three years later. But that offseason, Houston traded him to Cleveland. Big mistake. Lofton would become a six-time All-Star who batted .299 and stole 622 bases. He’s one of only two people to have played in college basketball’s Final Four and MLB’s World Series.

(The other is Tim Stoddard, who played basketball and baseball at North Carolina State before becoming a big-league pitcher. Incredibly, Stoddard attended the same high school as Lofton about 15 years earlier.)

Former Arizona basketball player Kenny Lofton, a longtime Major League Baseball player after his days as a Wildcat, smiles with his family before having his name raised in the UA men’s basketball Ring of Honor at McKale Center Saturday.

Lofton’s Final Four participation made him that much more appealing to Crist.

“That was a big part of my decision,” said Crist, who also scouted and signed St. John’s basketball player-turned-MLB pitcher Amir Garrett. “He knew what it was like to play in the limelight. He’s gonna want that in baseball. He wants that arena. He wants that attention.”

Crist didn’t want any attention when it came to scouting Lofton. Crist told the Astros not to send anyone to crosscheck his work. He didn’t want a rival team to discover this Tucson gem.

Scouts hear things, though. They would ask him, “Who’s that Lofton guy?”

“He’s a basketball player,” Crist would respond.

In reality, Kenny Lofton was so much more.

Former Arizona Wildcats men's basketball player and longtime Major League Baseball legend Kenny Lofton saw his name placed in the UA basketball Ring of Honor at McKale Center Saturday, March 2, 2024, during a UA blowout win over Oregon. (Courtesy Arizona Athletics)