In the fall of 1970, I was summoned to a press conference at Old Main and told that Utah State University would be changing its nickname from Aggies to Highlanders.

I returned to the student newspaper office and let the loathing flow.

My newspaper article and the outrage of thousands of Aggies didn’t have a chance. The USU’s president’s office had long ago decided that a school with renowned range science and forestry colleges could no longer attract students in suitable numbers.

Nobody in the culturally-evolving ’70s wanted to be associated with cow-milkers and hay-balers.

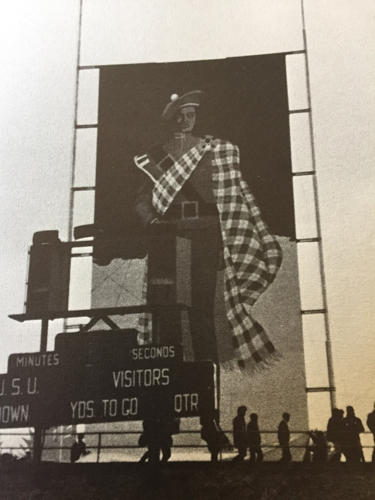

That week, under heavy security, the president’s office constructed a towering, 70-foot high painting of a Highlander behind the scoreboard at Romney Stadium. It was such a mammoth project— made of plywood — that it overlooked the beautiful Cache Valley all the way to Idaho.

At halftime of that week’s football game, men dressed in kilts and carrying bagpipes marched on the field, playing Scottish songs — although I couldn’t hear them because 20,000 people never stopped booing.

A university vice president held a brief Q&A session in the press box and went on and on about how much the school would grow by shedding its reputation as an agricultural school.

I remember Ray Herbat of the Salt Lake Tribune saying, “but this IS an agricultural school.”

That night, I drove my co-conspirators Dave Ringle and Steve Watts, whose father and two brothers had played basketball for the Aggies, to Jack’s Tire and Oil, my father’s gas station. We filled a five-gallon can with fuel oil.

We drove up Old Main Hill and parked in the Logan Cemetery, adjacent to Romney Stadium. About midnight we climbed over a chain-link fence and waited in the darkness. The one university policeman working the night shift was nowhere to be seen. There were no flammable structures — nothing but cement and blacktop — within 200 yards.

Dave brought a broom, with which to help spread gasoline over the lower surface of the 70-foot Highlander. Someone lit a match.

Poof! We ran for our lives, across the street and into the cemetery. The Highlander burned like the Fourth of July.

No one called the cops or the fire station. The plywood man in a kilt with a Scottish cap soon turned to ashes. And then it was gone.

A few days later, a USU vice president announced the school would reconsider changing the school’s nickname.

Aggies forever.

Being an Aggie isn’t a national brand, but when I was an impressionable young man growing up in Logan, Utah, the Aggies had a flow of NFL players — 16 in the 1960s alone — that exceeded both Arizona and Arizona State.

Merlin Olsen. Bill Munson. MacArthur Lane. The great Cornell Green. Earsell Mackbee. Altie Taylor. And on and on. My high school friend, Phil Olsen — Merlin’s brother — became the No. 4 overall selection in the 1972 NFL draft.

Hay-balers? Just an old agriculture school?

Utah State went to the Elite Eight in 1969, long before anyone in Tucson had heard of Lute Olson. The Aggies have gone to 19 NCAA tournaments. That’s four more than the Oregon Ducks.

Aggie blood flows with important names.

Tailback Louie Giammona led the NCAA in rushing in 1974 and 1975. NBA head coaches Dick Motta and Phil Johnson are Aggies. Remember the great LaVell Edwards, who built BYU football into Quarterback U? He’s an Aggie.

The two pillars of USU sports are Merlin Olsen and Wayne Estes. They are the Steve Kerr and Sean Elliott of Aggie sports.

Merlin, like Elliott, was home-grown. Estes, like Kerr, became the most beloved Aggie in history.

In 1965, the man Aggie fans referred to as “Baby Huey” averaged 33 points per game. He scored 48 points on a snowy February night, giving him 2,001 for his career. Unimaginably, he was killed an hour after the game, electrocuted, while stopping at the site of an automobile accident to see if he could be of assistance.

A live power line, dangling about 6 feet off the ground, had been severed from a light pole. It struck the 6-foot-6-inch Estes, a small-town superstar, a first-team All-American from Anaconda, Montana, in the forehead.

I cried and cried and cried, as did most people in the Cache Valley. The greatest Aggie was gone.

When the Aggies played again, Estes was replaced in the lineup by Gene Widmer, a young forward from Montpelier, Idaho. After a ceremony honoring Estes and his family, Widmer walked into a crowd of sad fans and tried to say something comforting.

He put his arm around me. He shook hands with my dad. Gene Widmer became my new favorite Aggie.

About 20 years later I moved to Tucson. Someone from the LDS Church knocked on the door and invited my family to a backyard cookout at the home of a Mormon bishop living nearby.

As I circulated among those at the party, I was introduced to the bishop. He was a tall man with a familiar face, who had become an executive at Tucson’s Raytheon plant. He asked where I went to college.

“Utah State,” I said.

“Small world,” he responded. “I’m an Aggie, too.”

“What’s your name?”

“Gene Widmer.”

We became best friends.

Aggies forever.