The night before Arizona was to play UTEP at the new Sun Bowl football stadium, Nov. 14, 1964, Wildcats coach Jim LaRue took his players to a movie near the UTEP campus.

Officials at the theater refused admission to the UA’s 10 Black football players.

Arizona athletic director Dick Clausen was so incensed that he vowed not to schedule another football game in El Paso. Clausen held firm to that decision. From 1965-69, the Arizona-UTEP game was always held in Tucson.

It was after that 1964 weekend that Clausen became dedicated to helping eliminate discriminatory practices of college sports. That repulsive experience at the El Paso movie theater became the genesis for the UA’s Black History Month. The celebration includes a Feb. 15 “Breaking Down Barriers with Arizona Athletics” Zoom conference that’s open to the public.

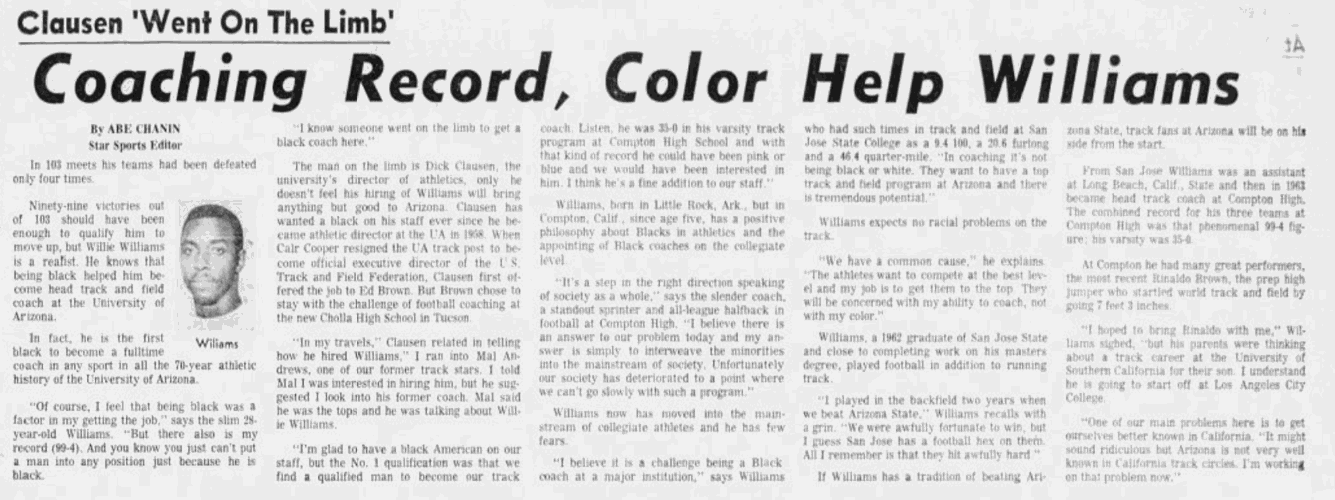

To help create change, Clausen became dedicated to hiring a Black head coach. That wasn’t just an idle vow. When UA track coach Carl Cooper resigned to become head of the U.S. Track and Field Federation, Clausen advertised the position nationally.

No Black coach applied.

“So I went looking for one,” he told me in a column published in 1998.

Clausen first had to make sure he hired the best man for the job. No Division I school in college sports had ever employed a Black head coach, in any sport. Hiring a Black head coach would create headlines from coast to coast.

Clausen couldn’t afford to be wrong.

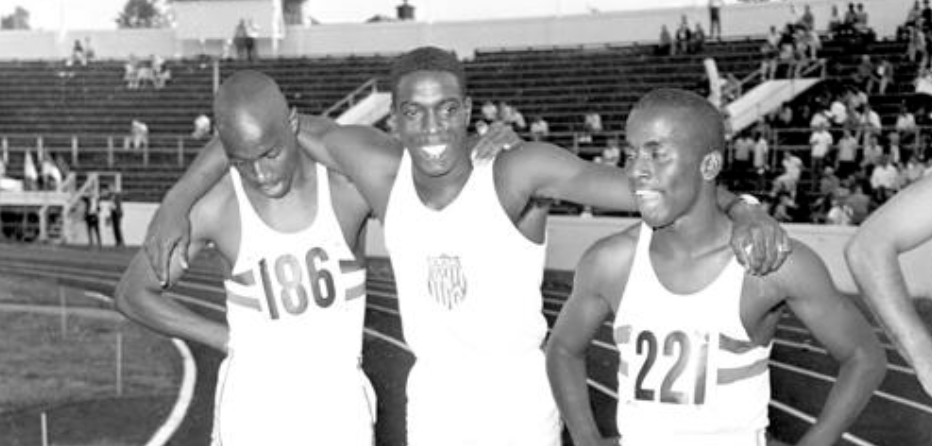

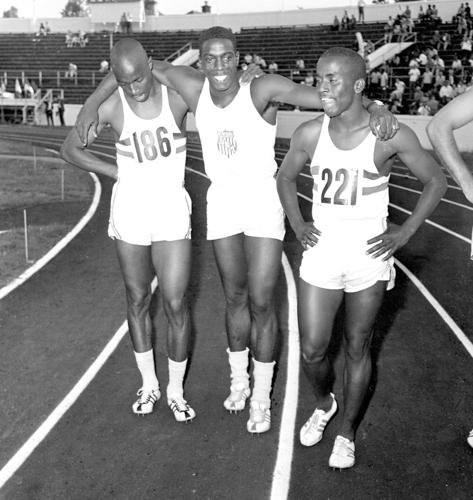

A few months later Clausen hired Compton High School track coach Willie Williams, a former world-class sprinter from Los Angeles and an All-American at San Jose State.

Williams was 28, a former USA National team standout paired with the great Bob Hayes. Williams had coached Compton to a 99-4 record and was in such demand that the Los Angeles Times reported he had earlier accepted a coaching job at Long Beach State, and then backed out.

Clausen’s first offer to Williams was rejected. He enjoyed his job in Los Angeles; Compton High was his alma mater. His wife, Margaret, was also from L.A. Undeterred, Clausen returned to Tucson and asked UA President Richard Harvill to increase the budget for track and field, including a higher salary for Williams.

It wasn’t that Williams insisted on staying in the comfort zone of Los Angeles. He was born in 1940 in segregated Little Rock, Arkansas. He and his family grew up in the deep South before moving to California. He knew racial tension up close.

Clausen’s second offer to Williams worked. On June 19, 1969, he became the first Black head coach in major-college sports history.

“Willie wasn’t afraid to be a pioneer,” Clausen said. “He took on that responsibility without expressing doubts.”

At the time, Arizona had just four Black employees in its entire athletic department: assistant football coach Willie Peete, assistant basketball coach Albert Johnson, and equipment room employees Ed Thomas and Phil Gaines.

So much has changed. The UA had 61 Black players on its 2020 football team. It has three Black head coaches: women’s basketball’s Adia Barnes, gymnastics’ John Court and track’s Fred Harvey. The school has 11 Black assistant coaches.

The UA hasn’t forgotten Willie Williams. When Black History Month began on Monday, assistant football coach Chuck Cecil quickly tweeted a notice of the celebration of Williams’ Arizona career. Williams’ oldest son, Greg, who works in the stock market business in Phoenix, answered Cecil’s message.

“Thanks Chuck, my mother and family appreciate this tweet and helping keep his accomplishments and memory alive,” he wrote.

The Williams family became much more to Tucson than just their father’s trailblazing coaching.

By the end of the 1981 track season, Greg Williams had made an impact in Tucson. He was a state champion in the long jump and set Sahuaro High School records that still stand in the 100 and 200 meters. His younger brother, Stevie Williams, was an all-state basketball player at Sahuaro who became a four-year starter at NAU, scoring 1,341 points.

Many of Tucson’s premier high school track and field athletes competed for Williams: Gus Brisco, Raul Nido, Rafael Ortega, John Dineen, Scott Hurlburt and so on.

Williams connected.

“He was the speaker at my first track banquet in 1973,” says former Sahuaro High track coach Bob Saxon. “He was an excellent coach and a student of the sport. He shared his Track and Field News magazines with me. He said, ‘Don’t lose these. They are my life.’”

Yet Williams’ coaching career ended in unspeakable tragedy.

On Jan. 14, 1982, the sprinters, high jumpers and javelin throwers who visited Williams’ modest McKale Center office were greeted by a locked door and a troubling sign on the door.

“Today’s practice is canceled,” it said.

Williams had taped the note to the door sometime that morning. He also went to a hardware store and bought a gun.

About 2 p.m., assistant coach Michael Bassoff found Williams lying on the floor of an equipment shed at what is now Drachman Stadium. The 41-year-old coach was dead from a single gunshot wound to the head. Police ruled it a suicide. There was no note; no ready explanation.

The grief and mystery of Williams’ death rocked the UA athletic department to its core.

“I was shocked; I liked him an awful lot,” says Benjie Sanders, a Tucson High grad who was a sprinter on Williams’ early UA teams and, later, a longtime Star photographer. “He was a very nice fellow. He was so vibrant. I had nothing but respect for him.”

Sanders, who is Black, said he did not notice any difficulties with Williams being accepted in Tucson.

“I never saw any problems; he got along with everybody,” Sanders says. “His wife was a very sweet lady. His kids were out there. I was so proud of him.”

Williams’ coaching career in Tucson wasn’t without problems. He inherited an old-fashioned four-lane track at Arizona Stadium so lacking in modern amenities that the Western Athletic Conference refused to hold its 1969 championships in Tucson. Until Drachman Stadium was built in 1981, the Wildcats had the worst facility in the Pac-10.

Williams had to hold a fundraiser, netting $60,000, just to keep the running surface up to safety code.

Once Arizona joined the Pac-10 in 1978, the Wildcats were at times overwhelmed by national track powers USC, Oregon, UCLA and Arizona State. All won NCAA championships in the 1970s. Those schools made track a priority; at Arizona, Clausen’s successors did not.

Yet Williams did well with a meager budget and inadequate facilities. His reputation went global. He was named to the Team USA coaching staff for the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics, and was long a part of the USA Training staff for the development of sprinters. In a life that ended in the prime of his career, Williams proved to be the right coach — the coach Dick Clausen started looking for in 1964.

As difficult as it is to believe, Williams has not been selected to the UA’s Sports Hall of Fame. Since his death, 42 former UA track and field athletes have been inducted, including nine coached by Williams.

For the UA to make Black History Month complete, it must do more than recognize Williams’ achievements this month. It must soon induct him into the school’s sports Hall of Fame and put closure to his legacy.