At the northwest corner of Block 35, Evergreen Cemetery, is a flat, 18-inch-by-9-inch stone marker that says, simply:

MOTHER

MARY ALMITTE MCCRAY

Oct. 23, 1910 — Jan. 15, 1975

The day Mary McCray was buried in that secluded back lot, her only child, Ernie McCray, was overcome by an overwhelming sense of loss. His mind went back to the February day in 1956 when he first stood in Block 35, saying goodbye to his grandfather, Charles A. Chatman, a sharecropper’s son who grew up working the cotton fields of Georgia.

His mother and grandpa were the only family members Ernie had ever known.

The stone marker for Charles A. Chatman is identical to that of his daughter. Ernie’s grandpa escaped the racial tension of the South by running away to Louisiana when he was 14, ultimately settling in a suburb of Pittsburgh and working as a laborer. He moved to Tucson in 1947.

That was about the time Ernie became a student at segregated Dunbar School, an austere facility initially known as “Colored School,” one that didn’t have a cafeteria or auditorium until 1948.

When Ernie left the Evergreen Cemetery that sad day in 1975, he drove to his home in San Diego, where he thrived as an educator and school administrator, a calling far greater than becoming Arizona’s career-leading basketball scorer from 1957-60.

On the drive, Ernie turned the radio to 1400-AM and listened to the final minutes of his alma mater’s basketball victory over UTEP. He heard announcer Ray McNally say: “Tonight’s game is dedicated to Mary Almitte McCray.”

When Mary McCray, a graduate of Howard University in Washington D.C., moved from Pennsylvania to Tucson in 1937 to help cure the tuberculosis in her right lung, it would be 15 more years before a Black man played basketball at the University of Arizona.

Times had changed. • • •

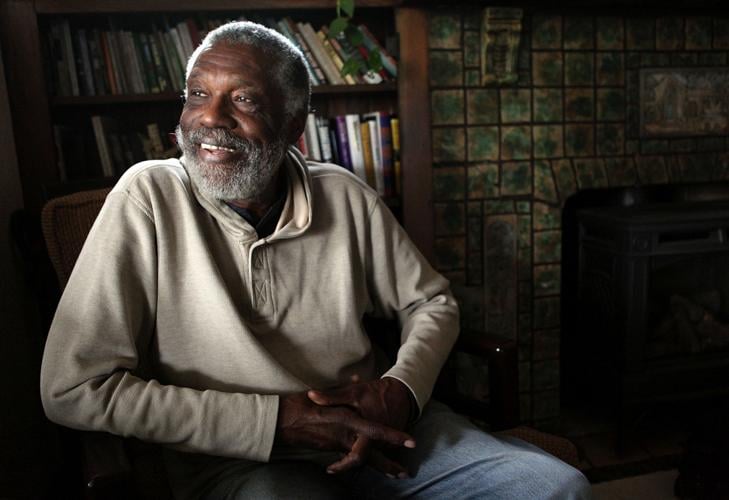

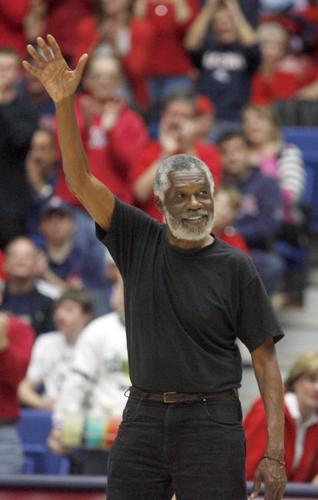

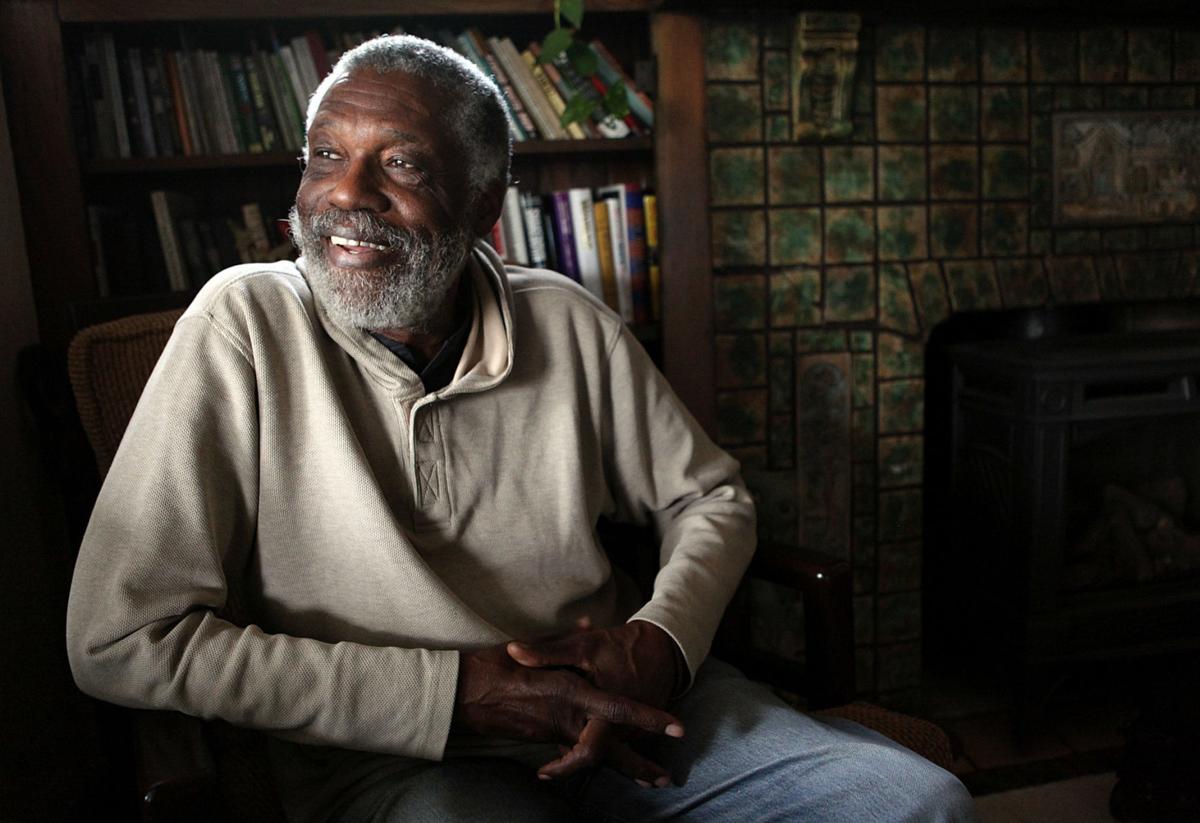

Saturday afternoon, 61 years after McCray became the most prolific scorer in UA history, his name will be placed in the school’s Ring of Honor at McKale Center.

He is not bitter that it took so long.

“To me, it honors not only my athleticism, but it honors my life,” he said in a Zoom conference Tuesday. “It puts my life in historical perspective.”

Ernie McCray probably wouldn’t have played at UA if a former Wildcat two-sport standout hadn’t been playing against him in a YMCA pickup game in 1956.

Despite leading Tucson High School to the state championship games of 1955 and 1956, McCray was not immediately recruited by Arizona coach Fred Enke. That seems stupefying now.

Enke’s teams of the mid-’50s had faded from their historic first-ever national ranking and visit to the 1951 NCAA Tournament. They had gone 8-17 in 1954-55, the year McCray emerged as the star player for Bud Doolen’s powerhouse program at Tucson High.

“Ernie was about 6-6 and, man, could he jump,” remembers Tom Hassey, then the Badgers’ starting point guard. “He was such a great athlete, one of two Black players we had. Ernie and Ira Andrews. But Ernie was just dominant. He was still very skinny, but you just didn’t see players like him in Tucson.”

McCray grew up with his mother in a small house just west of Stone Avenue at 901 N. 10th Ave. His father, an itinerant musician, was not part of his life. Ernie and his mother closely followed UA sports during the 1940s, a period that the UA’s athletic department employed just one Black man, Slim Williams, the equipment manager.

It wasn’t until 1952 that Tucson produced its first star-level Black high school basketball player, Amphitheater’s Jim Sparks. McCray would be next.

But after McCray graduated from high school, his only scholarship possibilities were at Eastern Arizona College and from the Kansas Jayhawks, who were looking for role players to help prize freshman center Wilt Chamberlain

Arizona? Nothing.

“It was a different time in Tucson,” says Hassey. “As a young boy, I didn’t realize that the Dunbar School was segregated. I was just blind about it. When I got to know Ernie, it was a real awakening; I was trying to take it all in. I never heard him complain. When we played at Yuma we roomed together, and I just loved Ernie. Everybody did.”

It wasn’t until McCray was playing pickup basketball at the YMCA after the ’56 high school season that Arizona freshman coach Allan Stanton, a standout Wildcat basketball/football player of the early ’50s, casually asked him where he was going to play college basketball.

“Maybe Eastern Arizona,” McCray said.

Stanton asked if he had talked to Enke.

“No.”

A day later, after consultation with Stanton, Enke finally contacted McCray and offered him a spot at Arizona.

“Allan was the best coach I ever had,” McCray says now. “He was everything to me.”

Stanton, who died last spring, graduated first in his class at the UA Law School and spent the next 50 years as an attorney in Phoenix. Had he not played in a YMCA pickup game against McCray that afternoon in 1956, McCray probably wouldn’t have been a Wildcat.

Now 82, retired from a career in which he was a teacher and principal in San Diego, working for the San Diego Youth Services Board of Directors and the Juvenile Justice Commission, McCray says that being added to the UA’s Ring of Honor “is the honor of a lifetime for me.”

But he doesn’t see it as an individual honor as much as one he can share with his school and his hometown.

An Arizona Daily Star headline tells of Ernie McCray’s record-setting performance on Feb. 6, 1960.

Despite her degree from Howard University, McCray’s mother was not able to get a job in Tucson commensurate with her qualifications. She sold Avon products door to door, worked as a janitor at the phone company, filed taxes for neighbors, gave them haircuts and cooked for them.

Finally, toward the end of her life, Mary McCray was hired to work in the business department of the phone company.

“My mother had a lot of concerns about the university and the town,” Ernie says. “When you experience something like that, it never goes away.

“But Tucson has gotten away from its Jim Crow days. The university has come so, so far. It’s like I’ve lived two lives. This (award) is big for me. I’m not a casual Tucsonan. My heart is there.”