Seldom-used Arizona linebacker Kevin Singleton made one tackle in the Wildcats’ upset victory over 15th-ranked USC, a 1990 game at the Los Angeles Coliseum that matched the Wildcats against the man who recruited Singleton to Arizona five years earlier.

Rather that escape to the Trojans’ locker room, USC coach Larry Smith jogged through scores of people in a tunnel leading to Arizona’s dressing room until he saw the young man in a No. 84 Arizona jersey.

Smith tapped Singleton on the shoulder. They embraced and talked for 30 or 40 seconds. As Smith left, he dabbed at the tears in his eyes. He wasn’t crying because the Trojans lost; he cried because Kevin Singleton had made the greatest comeback in Arizona football history.

“Larry was such a class act,” Singleton, 52, says now.

“A lot of people hated him when he left for USC, but I understood. I was only 18, but I knew it was a lifetime decision and that he had to go. I never took it personally.”

Today, Singleton coaches for Larry Smith’s son, Corby, who is head football coach of the Tempe McClintock High School Chargers.

It has been an emotional journey, 30 years of healing, growth and challenges that have tested his character and strength.

Two years before that 1990 game at the Coliseum, Singleton made 16 tackles against the Trojans. Along with his twin brother Chris, Kevin was on a fast track to the NFL, a 6-foot-4-inch, 235-pound linebacker with speed, toughness and football instincts that you can’t teach.

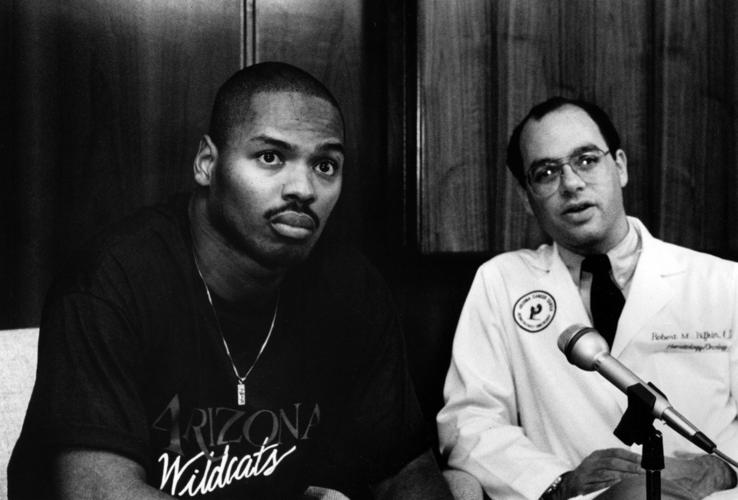

But 30 years ago last month, after a persistent pain in his right shoulder became too much to ignore, Kevin Singleton sought medical help. He was diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

In a press conference at the University Medical Center, Dr. Robert Rifkin told reporters that Singleton had a “40 to 60” percent chance to survive.

The desperate news shook the UA sports community like few events in the 120-year history of Wildcat football.

“I was crushed, I was angry, I was scared,” Singleton remembers. “I always tried to show a brave face, but I went through a depression. I knew I couldn’t pursue my dream of playing pro football.”

UA linebacker Kevin Singleton celebrates a defensive stop during the Wildcats’ win over Arizona State in 1988. One year later, Singleton was diagnosed with leukemia.

Last month, Singleton spent time in Omaha, Nebraska, visiting his mother, Margaret, who is suffering from Alzheimer’s-type disease. Kevin and Chris Singleton were born in Omaha in 1967; their parents separated when the twins were 10, and the boys moved with their father to Parsippany, New Jersey. Kevin Singleton became estranged from his aunts, uncles and cousins.

Kevin’s journey home was another step in a 30-year healing period from the summer of 1989 when he spent weeks at UMC undergoing chemotherapy to keep him alive.

“I went to Omaha with no idea what to expect; I’d basically missed a huge part of my life, my family,” says Kevin. “My mom is in an assisted living facility, but I found nothing but love once I got there. I got to know my cousins, aunts, uncles. I was humbled. I’m going back in October.”

The Singleton twins arrived in Tucson in the summer of 1985, surely the most prized recruiting package in UA football history. They declined offers from Notre Dame, Penn State and Nebraska to play for the Wildcats. The sky was the limit.

Chris went on to be the second-highest draft pick in UA history, No. 8 overall to the New England Patriots in the 1990 draft. He played eight productive NFL seasons and then worked 20 years in the pharmaceutical business. He retired a year ago and now is an assistant coach at Gilbert High School.

Chris Singleton was a world-class linebacker, but his greatest day came neither in the NFL nor at Arizona, but the January 1990 afternoon when he underwent a four-hour bone marrow surgery at UMC, sharing the bone marrow that would save his twin brother’s life.

Although he never regained his pre-cancer strength and endurance, Kevin Singleton was granted a sixth year of eligibility by the NCAA and spent the 1990 and 1991 seasons on Arizona’s roster. He was voted team captain in 1989, even though he didn’t suit up or practice.

His coach, the late Dick Tomey, referred to Kevin as “the greatest Wildcat.”

Singleton earned a master’s degree at Arizona, spent two years as a graduate assistant coach on Tomey’s staff and then took an entry-level job with Cal State Northridge’s football program. When the school eliminated football, Singleton was hired to work in the fitness equipment business by an old Wildcat teammate, Donnie Salum.

Kevin Singleton, left, with Dr. Robert Rifkin, an oncologist from the University Medical Center, met the media after Singleton was diagnosed with leukemia in 1989.

About a year ago, Singleton left the fitness business to become the head of security of McClintock High School and to coach for Larry Smith’s son.

“My story isn’t a rags-to-riches as much as it’s a make-the-most-of-life,” Singleton says. “I was successful before leukemia, and I’ve been successful after beating leukemia. The message I’d pass along is that, holy smokes, be positive, gracious, humble and love life.

“I love my security job at McClintock, but I see it more as being a mentor for the kids. I can be a problem-solver here. I teach life skills. You don’t have to survive cancer to be a positive force in life.”

Singleton hasn’t been problem-free since he left the cancer ward of UMC in the spring of 1990.

Last fall, his girlfriend, Susan Caraway, the mother of their 16-year-old daughter, Kaelan, died of anaplastic thyroid cancer. It was devastating. Susan was only 54. In addition to his jobs at McClintock, Singleton is now a single dad.

“I’m not sitting around asking, ‘who am I to deserve this?’ ” he says.

“These experiences have made me fight. You can’t just shake it off. Watching Susan pass away, knowing how it devastated Kaelan, made me angry, but it also let me know that I’ve got to fight through this the way I fought through leukemia 30 years ago.

“If I’ve learned anything, it’s that I’m not a quitter.”