Corey Steinbrecher did the right thing when it counted. And, for that he will always be content.

Yet many others in the sport of cycling didn’t. The Tucsonan said a generation of riders were lost to blood doping, including many of his friends.

Steinbrecher is 36 now, more than 10 years removed from his time as a professional cyclist. But when he sees a race on TV, like the recent Tour de France, his heart rate jumps. The sport still grabs him, despite how his career ended.

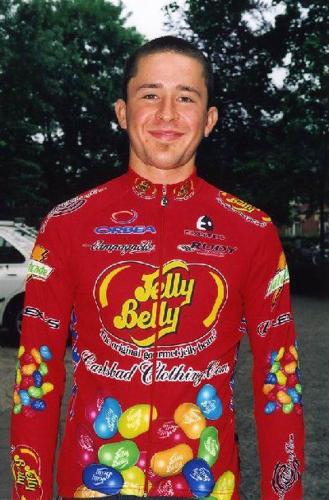

“I’m still enthralled with cycling,” said Steinbrecher, who raced professionally for seven years as part of the Jelly Belly racing team and the U.S. national team. “It’s not the most exciting thing to watch, but it stays on. I don’t miss the amount of work it takes to be at that level. I think very few people could realize how much work it took. I do miss the race, what it was like to compete.

“When I ride now, I have one rule: If you’re not smiling, you’re messing up. You can ride hard and still have a smile on your face. Those last few years of cycling I don’t remember that.”

Corey Steinbrecher

Today, Steinbrecher’s life is much different. He is no longer cycling 90 events per season in Europe. In May, he graduated from the UA’s medical school. He’s currently a resident in a Chattanooga, Tennessee, hospital’s emergency room.

He’s still part of a team.

“In medicine, it takes all types of people. There is a massive hurdle to overcome,” he said. “When I’m done with my role, my teammate will take over. I like to think of them as my teammates. The oncologist will take it over the finish line.”

Steinbrecher began racing as a 12-year-old in his native Illinois. Success led to regional races, including a World Cup in Canada when he was 17 years old. Steinbrecher graduated from high school early, competed for the U.S. Junior national team and U23 national team in Europe and signed with Jelly Belly to race in the U.S.

His name may sound familiar to Tucsonans as he won the 2003 Tucson Bike Classic. Yet, winning is not what Steinbrecher remembers about that race.

“The bigger story is that a racer, Garrett Lemire, ended up dying in a crash. I remember seeing his parents the next day at the start line; that visual is burned in my memory. In life some moments are extra vivid,” he said.

Tucson became Steinbrecher’s home base. He and other elite cyclists would ride for six, sometimes seven hours a day. He admits now that he overtrained.

“At this point, you just can’t hope to be in it — you have to try to win it. It’s the only way to get there,” he said. “Some part of me was just happy to be there. I had a lot of pride at 19, 20 years old, just racing those races. I dreamt of doing this. It was surreal.”

At some point, Steinbrecher’s dream looked different.

Performance-enhancing drugs (PEDs) were everywhere in the sport of professional cycling, he said. The risks were low; even those who got caught would serve a light suspension — two years — and then return to ride again on another team.

“To be honest, doping was probably the best thing you could do for your career,” said Steinbrecher.

He decided it wasn’t worth it.

“I realized I needed something more than just a bike, that maybe it was just not for me,” he said. “Some part of me decided that cycling was not the end game for me. I needed more than that solitary focus. Maybe the iron wasn’t hot enough to strike it. If I was that age and lavished with success early, maybe it would have been different.

“Now, ‘I didn’t dope’ isn’t a bragging point. Not to say it’s wrong. I don’t judge people who did it, and that may sound crappy. For me, I understood why they did it. … As bad as I wanted to be great, I didn’t want to sacrifice who I wanted to be at some point in the future. I don’t know if it would have, but not knowing isn’t a good excuse.

“At the end of the day, I am glad I didn’t, but the results reflected it — there was a lot of quiet, hard work to give others the win. I’m glad I had that role, it’s where I got my motivation.”

Steinbrecher’s career ended in 2013, when his body couldn’t take the rigors of cycling anymore. It was near the end of a European racing season, and Steinbrecher was homesick and tired.

“I did the bloodwork and my hematocrit rate was 39, which is really bad. There is a lot of room to improve on blood. They never said ‘do you want EPO?’” Steinbrecher said, referring to the banned substance Erythropoietin. “But the implication was there that if you bring it up and change it … a 49 rather than a 39 … you’d be that much better, you can win, and you can make more money. Maybe a little of me quit that day, though. To be honest, that’s the first time I’ve said part of me quit.

“Maybe if all I wanted to be in my life was a cyclist, I’d have done it. Maybe if I didn’t have a dad who would have laid the biggest guilt trip in the world on me, I wouldn’t have done what was right. I knew doping wasn’t right.”

Steinbrecher’s father, Hank, was the Secretary General of the U.S. Soccer Federation from 1990-2000. Because of that, Corey saw up close the best of sports — the U.S. women’s soccer team winning the 1999 Women’s World Cup. He also saw the worst, often up close.

Faced with the biggest decision of his career, Steinbrecher decided the juice — as the saying goes — wasn’t worth the squeeze.

“I’d love to say he did it for me,” said Hank Steinbrecher. “But it’s totally him. He has a high moral fiber and a strong work ethic. I am proud of him and applaud him for it. It was a deciding point in his life.”