On the days Art Luppino plays golf at Comanche Trace Country Club in Kerrville, Texas, he carries his clubs in an "Arizona Wildcats'' bag. He often wears a hat with an "A'' logo.

"I just strut it around,'' he says with a chuckle. "I don't neglect to tell everyone I bump into that I went to Arizona. This is Texas A&M territory.

Greg Hansen is the longtime sports columnist for the Arizona Daily Star and Tucson.com.

"But I'm so proud of my school that I think the Aggie and Longhorn people are getting sick and tired of me.''

But it's not what it seems. Art Luppino, the famed "Cactus Comet'' of Arizona football lore, is one of the most humble and unassuming athletes I have ever known.

Once, while dining at a Tucson restaurant with Luppino and 1940s Arizona standout John Black, the Comet suggested that any of his fellow running backs on the 1954 and 1955 Arizona football teams also could've led the NCAA in rushing.

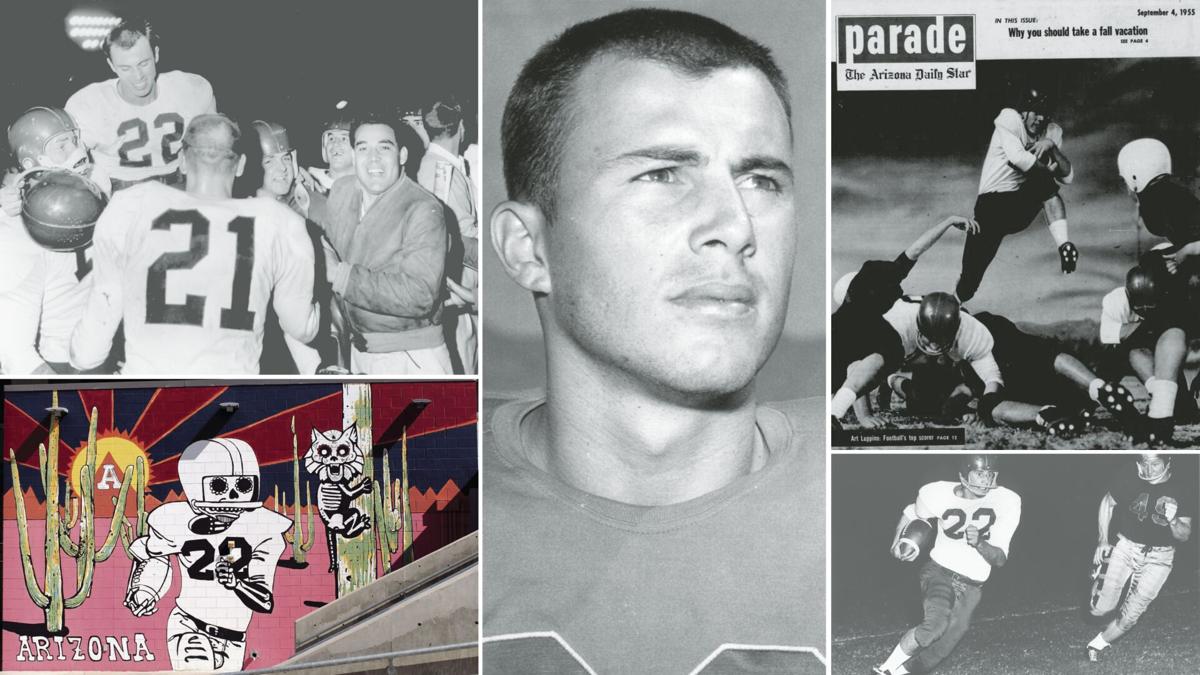

Art Luppino is hoisted onto the shoulders of his Arizona team after a victory. Luppino became a national star with the Wildcats, only to suffer a concussion and serious knee injury that hurt his chances of playing professionally.

"You're being too modest,'' said Black.

"How so?'' asked the Comet.

"Because no one's going to believe you.''

• • •

Art Luppino

The distance from Luppino's home in Kerrville to the Alamodome in downtown San Antonio is 61 miles, but he is not going to hop on Interstate 10 for the short drive to watch his alma mater play Oklahoma in Thursday's Alamo Bowl.

At 89, his eyes don't work the way they worked when he rushed for a prodigious, almost unbelievable 226 yards against New Mexico State on just six carries in 1955. He recently had a pacemaker implanted to regulate his heartbeat — "it's my fourth pacemaker,'' he says, "maybe they should just install a zipper'' — and, besides, no one at the UA thought to invite him to San Antonio, make him team captain for the day, or celebrate Luppino's almost-storybook Wildcat career.

"Besides,'' he says, "my wife, Camille, had COVID this week. So I'll watch on TV. Maybe I'll wear my letterman's jacket. I still have it. There's a leather tag with my name on the inside. It's dark blue with white leather sleeves. Maybe it'll be a good luck charm for the boys.''

In the fall of 1953, Luppino paid $7.50 for a one-way ticket on a Greyhound bus from San Diego to Tucson for his first semester at the UA. He was assigned to a dormitory room on the east side of Arizona Stadium, just above today's Zona Zoo section and not far from where a mural depicting the Comet sits facing East Sixth Street.

The surfer dude from San Diego, son of a career Navy man, was the first in his family to attend college. By the time he completed his eligibility in 1957, he was the most famous athlete in UA history, or no worse than 1-A with the late John "Button'' Salmon, he of the "Bear Down'' legend.

Luppino was given the nickname "Cactus Comet'' in 1954, his sophomore season, when he rushed for an NCAA-high 1,359 yards, becoming the fifth man in history to rush for 1,000 yards in a college football season. He was on the cover of Parade Magazine, a Sunday supplement to most U.S. newspapers, with an estimated circulation of seven million.

Today, the Comet lives quietly in the Texas hill country, keeping his college days to himself for the most part.

But the secret got out.

Last summer, Comanche Trace golf companion Buck Buchanon sent an email to the Star indicating he had read about Luppino in the Star's online archive.

"I never knew him as anything other than he is a nice elderly gentleman who was very well read and interesting to talk to,'' Buchanan wrote.

Art Luppino made the Sept. 4, 1955, cover of Parade magazine.

"Imagine my surprise when I found out he was a legend in Arizona football. He never mentioned it. When I asked him about it, he didn't say a word about the awards he won or the records he set. About all he had to say was, 'I really just wanted to play baseball.' To be honest, he talks more about his time serving in the Korean War than any of his sports achievements.

"Art is still in good shape. His mind is sharp — his hearing, not so good. He's a quiet, humble man, and I'm proud to be his friend.''

• • •

It's somewhat ironic that after Luppino moved from his home at the Tucson Country Club about 20 years ago that he wound up in Texas. The move was predicated on his wife Camille's roots; she grew up in Dallas before attending Arizona and meeting Art in 1955.

Art Luppino’s 1955 Parade magazine photoshoot was big news in Tucson, which was not used to national attention when it came to football.

But there is no question that Luppino's football career, his Cactus Comet days, went down a dark road on a November night, 1955, in Lubbock, Texas. That's the night a Texas Tech Red Raider lineman sucker-punched Luppino in the face — his helmet did not have a facemask — and knocked him out.

"I had such a severe concussion that I never got over it,'' he says. "I didn't play a game again without getting a concussion. That night in Texas basically ended my football days. I was never the same.''

The melee at Texas Tech was widely reported in Tucson. The outrage was palpable. The "goons'' from Texas Tech targeted Luppino, knocked him out, and won 27-7. And even though Luppino completed the ’55 season with 1,313 yards, again No. 1 in college football, he says "I shouldn't have played again after I got mauled at Texas Tech.''

He was limited in 1956, gaining a mere 327 yards. A knee injury suffered in training camp limited his elusive nature, his Comet-ness. A year later, the Washington Redskins invited Luppino to training camp, but his year-old knee injury had not improved. Luppino has told me several times that UA team doctors failed to treat his injury with nothing more than a "tough it out'' diagnosis.

Art Luppino led the NCAA in rushing in back-to-back seasons of 1,359 and 1,313 yards, then unprecedented in college football.

Instead of a career in the NFL, Luppino became a success operating a fitness center and gun shop near San Diego. He also taught school for 22 years. It took him several decades to get past the way his UA career ended, a bitterness that stuck with him until the 1990s.

But now his name is on display for posterity at Arizona Stadium, featured on the top row of the Ring of Honor after his No. 22 was the first jersey retired by the UA program.

"I had my time and am thankful to the university, but those days are gone,'' he says.

"I've watched all the games this year, and the team really amazes me. I don't know how they could go from being so poor to being such a good football team in a short time. I'm so proud. I think they're going to win.''

"The Cactus Comet Rides Again" mural, on the southeast corner of Arizona Stadium, was created by former UA art student Danny Martin. It depicts legendary 1950s UA football player Art Luppino, who led the the NCAA in rushing as a sophomore in 1954, and again in 1955. His 1,359 yards in 1954 marked just the fifth time a player had rushed for more than 1,000 yards in a college football season.

Arizona head coach Jedd Fisch held a news conference this week and discussed the Wildcats ending the regular season 9-3, bowl game prep, coaching contracts and increasing the salary pool, transfer portal and potential bowl opt-outs, among other topics. Video by Justin Spears / Arizona Daily Star