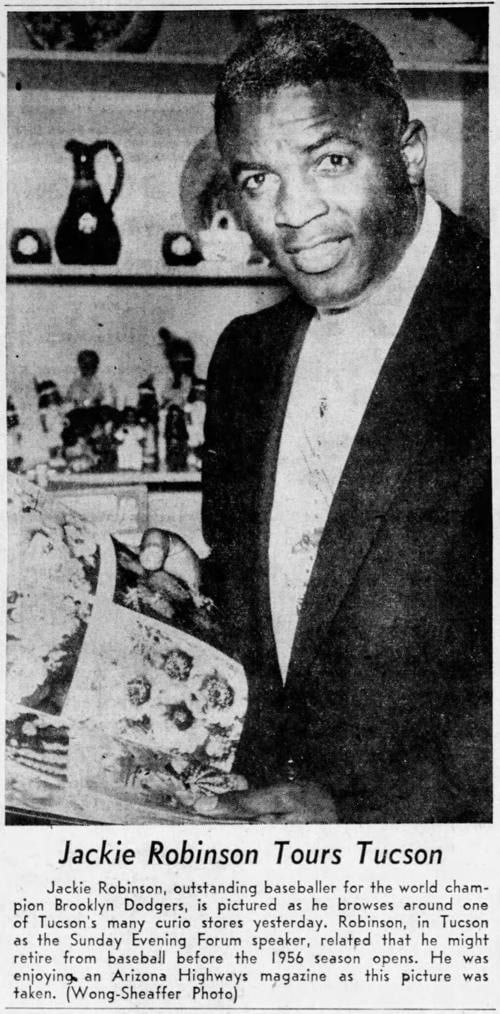

Jackie Robinson’s first visit to Tucson was fully booked, end to end. After he flew into Tucson the morning of Nov. 19, 1955, Robinson was greeted by a representative from Arizona Highways magazine, who gave Robinson this busy two-day itinerary:

Speak at the El Conquistador Hotel;

Attend the Arizona-New Mexico football game Saturday night;

Get up early Sunday to speak at the Tucson YMCA;

Attend church services at Catalina Methodist;

Go to the horse races at Rillito Racetrack;

Speak at the Sunday Evening Forum at the UA.

It had been eight years since Robinson became the first Black ballplayer to appear in the major leagues, but it was Tucson’s first chance to hear his message. Robinson was treated like a celebrity.

When asked what he thought of Arizona’s 27-6 victory over New Mexico, Robinson, a former standout running back at UCLA, spoke of Arizona’s Art Luppino, the Cactus Comet, who rushed for 139 yards.

“He made the rest of the players look like they were standing still,” he told the Star.

But it was the UA athletic department that had been standing still. The school’s ‘55 football team had just two Black players, Ed Brown and Clarence Anderson.The basketball and baseball games both had one Black athlete — Hadie Redd and Marty Hurd, respectively.

Arizona still scheduled games at Border Conference rival Texas Tech, which did not allow Black athletes to play on its campus or in Lubbock, a discriminatory policy that led Border Conference charter member New Mexico to leave the league in opposition five years earlier.

It wasn’t until Robinson was in his third year with the Dodgers, 1949, that the UA broke its color barrier, inviting Fred Batiste to enroll and play football and track for his hometown school.

In some form, almost every college and every sport in America benefited from Robinson’s courageous and dignified career. Friday marks the 75th anniversary of Robinson’s first big-league game, and Major League Baseball celebrates the occasion by outfitting every player, on every team, in Robinson’s old No. 42 jersey.

It would be wonderful, if overdue, for Arizona to someday celebrate Fred Batiste’s 1949 season, make it a special opportunity for any Wildcat football player to be allowed to wear Batiste’s old No. 20 jersey each season, or put his jersey on display at Arizona Stadium.

Much like Robinson, who didn’t get his crack at the big leagues until he was 28, Batiste was 24 when he suited up for the 1949 Wildcats. The state’s leading prep athlete of 1943-44 — Batiste was an all-state running back and Arizona’s track and field athlete of the year — spent two years in the Army during World War II and two years playing football and track at Compton Junior College in Los Angeles.

Only then was he encouraged to return home to play for the Wildcats.

In September 1949, Arizona athletic director Pop McKale said “if (Black athletes) enroll here they will be treated the same as other athletes. I will personally help them all I can.”

Batiste played for two seasons. He endured the indignity of not being allowed to accompany the Wildcats to a 1949 game at Texas Tech, and to a 1950 game at UTEP. Before his debut game, Sept. 24, 1949 against New Mexico State, Batiste told the Star he had been welcomed by his all-white teammates.

“They are a swell gang,” he said. “I felt that I fit in the first day at (training camp). I sure hope I can make the squad.”

After Batiste became the first Black athlete to earn a varsity letter at Arizona, Star sports columnist Abe Chanin wrote that the Batiste “shattered precedent in a grand manner.”

A starter on both offense and defense, Batiste had a career moment in his final college game, 1950, against Iowa State, sort of like Jackie Robinson stealing home in a World Series against Yogi Berra and the Yankees. As Iowa State drove deep into Arizona territory in the game’s waning seconds, Batiste broke up a pass on the game’s final play, saving a 27-26 victory. He had done the same thing a few weeks earlier on the final play of a 32-28 victory over Hardin-Simmons.

Now, 72 years later, it is sad that the school has not inducted Batiste into the school’s sports Hall of Fame. Redd, the school’s first Black basketball player, was finally inducted in 1992, and Hurd, the school’s first Black baseball player, was inducted in 2008.

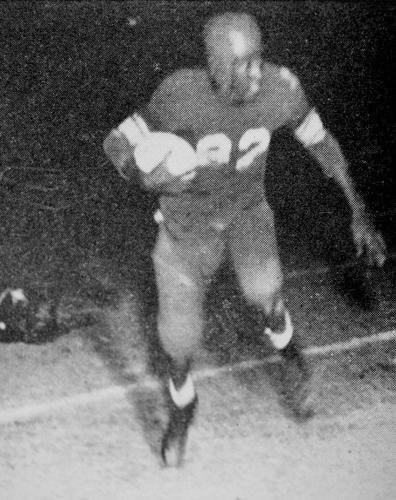

Fred Batiste was a football and track star at Tucson High who went on to play running back at the UA.

But nothing on Fred Batiste, who died in 1978 from complications related to diabetes. Batiste worked in the airline industry in Los Angeles. It is an incomplete chapter in the history of Arizona sports.

It’s not that Arizona didn’t fight the segregation policies of fellow Border Conference members Texas Tech, Hardin-Simmons and UTEP. It did. The Journal of Arizona History devoted the first 71 pages of its Winter 2021 edition to the racist policies of the Border Conference (1930-60) and Arizona’s futile efforts to end segregation.

C. Zane Lesher, a longtime UA tennis coach who became the school’s faculty representative to the Border Conference, said that “our original sin was ceding too much power and influence to the Texas members.”

That’s why Arizona left the Border Conference after the 1960 season and was proactive in creating the WAC. Lesher said that Arizona would no longer be affiliated with schools that “embraced value systems antithetical to American democracy.”

But it took too long. It was 13 years after Robinson broke baseball’s color barrier, and 11 years after Batiste became Arizona’s first Black letter-winner.

The Batistes are regarded as the greatest athletic family in Tucson history. Fred’s oldest brother, Joe, broke U.S. records in the hurdles while a student at Tucson High. Brothers Ernie and Frank were similarly outstanding THS athletes.

But they encountered great difficulties in 1930s and 1940s Arizona.

Tucson High didn’t allow Joe Batiste to play football until Mesa High School tried to get him to switch schools. Then Joe played football and became the state’s 1938 Player of the Year. His chance to be on the USA Olympic teams of 1940 and 1944 were ended by World War II.

Frank Batiste set a state record in the low hurdles, was an all-state football player, but was not allowed to play at Arizona. He set the NJCAA record in low hurdles at Compton College. Fred followed him to Compton.

“Through the years, the racial prejudices of Tucson have changed,” Ernie Batiste told me. “But I’ve always wondered how it would’ve been for my family, my brothers, to have been given the same treatment that Tucson gives its black athletes now.

“We just came along at the wrong time.”

Thanks to Jackie Robinson and Fred Batiste, there are no more “wrong time” stories of Black athletes in Tucson.