Taxing drivers by mile; swallowing made easier; boy trapped in car seat

- Updated

Odd and interesting news from the Midwest.

- By NICK HYTREK Sioux City Journal

- Updated

By NICK HYTREK

Sioux City Journal

SIOUX CITY, Iowa (AP) — Each morning when Floyd Food & Fuel opens, a worker walks outside to take a look at the six gas pumps.

"We go out every day and check, open the covers to see if they've been tampered with," said Terri Carlson, manager of the store.

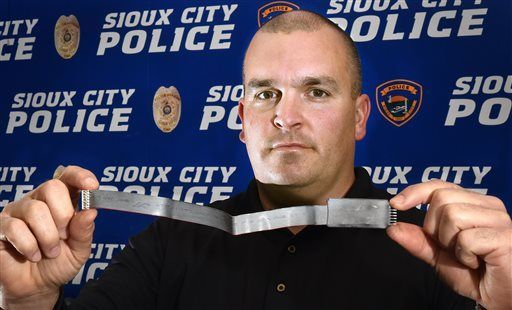

Tampering may be a sign that someone has installed a credit card skimmer inside the pump. The small electronic devices read information from customers' debit or credit cards, and criminals then use that information to create new cards to make fraudulent purchases on the owner's account.

"They open the door to the pump and attach it to the wiring inside so you never see it," said Sgt. Chris Groves, of the Sioux City Police Department's investigations bureau. "You or I don't know until we start seeing charges on our credit cards."

The Sioux City Journal (http://bit.ly/1SNnHnw ) reports that Skimmers have been found in three gas pumps in Sioux City in the past six weeks, most recently at the Cenex station at 1800 Highway 75 North on Tuesday. Other skimmers were found in late February at Cubby's and Select Mart in late March.

When a customer inserts a card into the skimmer, his or her account information is swiped and stored on the device, which criminals later retrieve or access remotely through a wireless device in order to download the information. Groves said the skimmers found in Sioux City all were the type that must be retrieved.

Unlike ATM skimmers, which are installed to the exterior of the machine, gas pump skimmers are installed in the pump's interior, usually inside the panel that houses the card reader and receipt printer. It's a panel that workers must access to change paper and is usually not sealed with a fuel pump inspector's security label. Inspectors check the pump's measuring accuracy by accessing a different panel, Groves said, then seal that panel.

Unless you see someone install the skimmer, it's hard to determine who put it there, Groves said, so police are encouraging gas companies and owners of gas stations and convenience stores to take extra steps to ensure security at their pumps.

"We would encourage all owners to do something to prevent unauthorized persons' access to the machine," Groves said.

Store owners are increasing their vigilance.

Ahson Alahi, who owns the four Select Mart stores in Sioux City, said workers inspect the pumps daily for signs of tampering. Extra locks have been added to pumps, but someone somehow unlocked the pump at the Gordon Drive store to install a skimmer. Alahi said that pump would not work the next morning, and the skimmer was found by police who were called to investigate. No data from customer cards had been downloaded onto the skimmer, he said.

Alahi said he has installed new pumps that are harder to tamper with at two of his stores, and the older pumps will eventually be replaced at his other two stores. Store employees continue to keep a close watch on the pumps through store windows and on surveillance camera monitors.

"We're watching. If somebody's playing with the pump, an employee would notice it," Alahi said, though he added that three of his stores are closed overnight.

At least one larger company has implemented additional security to try to discourage pump tampering.

Kristie Bell, director of communications of Kum & Go, a West Des Moines-based company that operates more than 430 stores in 11 states, including 10 in Sioux City and the metro area, said the company in 2014 began placing security labels on gas pump panels housing the receipt printer and card reader. Workers check pumps daily to see if the labels or pumps show any signs of tampering.

"If it appears to have been tampered with, we shut down the pump and have it inspected," Bell said.

The Iowa Department of Agriculture and Land Stewardship's Weights and Measures Bureau inspect gas pumps annually, and inspectors have begun checking pumps for skimmers during the inspection, department communications director Dustin VandeHoef said. Inspectors have found a couple skimmers, including one of those in Sioux City.

"It's kind of a new focus for us," VandeHoef said.

___

Information from: Sioux City Journal, http://www.siouxcityjournal.com

An AP Member Exchange shared by the Sioux City Journal

- By CORY MATTESON Lincoln Journal Star

- Updated

LINCOLN, Neb. (AP) — For the past 44 years, Terry Scott has been, as he described it, "one of them nasty ol' truck drivers." The Gretna resident did runs out to Cheyenne and back three times a week up until Valentine's Day this year. He was on mandated rest in Cheyenne that night when the phone rang.

"He jumped out of bed to answer the phone, and he fell on the floor," his wife, Debra, told the Lincoln Journal Star (http://bit.ly/1S9tfsC ).

Scott had suffered a stroke. The trucker was air-lifted early Feb. 15 from Cheyenne's hospital to one in Denver, where he spent 10 days in intensive care and a little over two weeks total before he could return closer to home.

On Wednesday, his vigorous handshake betrayed the Madonna Rehabilitation Hospital medical bracelet on his right wrist. An underlined message on the dry-erase board in his room announced his scheduled discharge date, April 13. It was lunchtime, and Scott was deliberately eating a French dip sandwich that had been ground into a coarse puree, soft carrots and an extra side of gravy. He drank grape juice and milk, both thickened with a honey-based solution in an effort to prevent it from going down the wrong pipe.

Eleven years ago, he said between bites, he went through radiation treatment for larynx cancer. So he knew from experience, as his body slowly regained strength, that he'd have to relearn things that once felt automatic, even something as simple as swallowing.

But swallowing, it turns out, isn't so simple.

"Swallowing is the single-most complex system in the human body," said Angela Dietsch, who teaches the graduate-level swallowing disorders class at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. "It involves 26 pairs of muscles, five cranial nerves and a 1.5-second process. How's that for intimidating?"

It's a process that often breaks down in patients seeking care for strokes, traumatic brain injuries, throat cancer and brain cancer. A symptom of a swallowing disorder — feeling like food is often stuck in your throat, gagging or coughing regularly — can be a precursor to a diagnosis of a degenerative disorder such as Parkinson's, muscular dystrophy or ALS. The muscles required to swallow can atrophy even more during the time a patient spends connected to a feeding tube.

"Most people don't even know there's such a thing as a swallowing disorder until somebody they care about has one," said Dietsch, an assistant professor in the department of special education and communication disorders at UNL. "But if you were to sit in Denny's on a Tuesday night or wherever and just start listening to how many people cough or clear their throats while they're eating, it's a lot of people. Which is not to say that all of them have a swallowing disorder, but it definitely starts to raise your alertness to the fact that it doesn't take much for that process to go haywire."

There is a name for the condition when the process has gone haywire — dysphagia. Because it often affects people who are undergoing treatment for life-or-death conditions, correcting a swallowing disorder was often an afterthought at best. But more and more, therapists and researchers are focusing on dysphagia.

"I can't imagine — even with as much time as I have spent working with people who have these kinds of issues, and sitting around the table with these people and their families -- I cannot even begin to imagine what it would be like to have that whole section of what is enjoyable of life be no longer a part of things," Dietsch said. "As cool as I think all of the science about it is, that's what makes me continue to work on it."

At Madonna Rehabilitation Hospital, patients being treated for dysphagia spend time in dining groups, where therapists monitor their swallows, said Teresa Springer, a Madonna speech-language pathologist who also teaches at UNL. She and other pathologists routinely study X-ray videos of patients who eat or drink solutions coated with barium, to follow the trail of food through, ideally, the esophagus.

And they also work the patients hard, said Terry Scott. The therapists drill into you a method for an activity you never thought about -- chin down, small bite, two swallows, small sip of liquid to wash it all down. Therapy methods can involve everything from muscle-stimulating electrodes to sipping air through straws twisted into knots. Madonna's patients with dysphagia are among the most vocal, Wagner said. Pronouncing words that include Ks and hard Gs work the muscles at the back of the tongue. Belting out an "E'' sound in falsetto can strengthen muscles used to swallow.

"Sometimes, our patients are loud," she said.

"Sit in here and sound like a little songbird," Terry Scott said.

"And that's kind of the new thing now, is we want our patients while they're going through radiation to keep working on their exercises," Springer said. "So we teach them their exercises before they go to radiation, so they're not losing as much muscle mass. It's kind of like, if you don't use it, you lose it. And so that's what they're learning now. That's what research is showing."

Scott said that when he went through treatment for cancer, he lost the ability to swallow for four months.

"They didn't offer any exercises then," Scott said. "I just had my radiation, then go back home. I come back the next day, radiation."

Springer said that treating dysphagia head-on is a developing field. There's not much research on the subject compared to other life-altering conditions, she said.

"Years ago, if people had a swallowing problem, they just realized there was nothing they could do for them, or maybe just modify their diet, and that was it," she said. "But no one wants to be on a puree diet any longer than necessary. So that's always our last resort."

One of those helping to build the body of dysphagia research is Dietsch. Before joining the faculty at UNL last fall, she spent three years conducting dysphagia research during a post-doctoral fellowship at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center.

The primary goal of the residency was to build a massive database to track dysphagia treatment in a group of patients who had not been studied much previously — those who lost some or all of their swallowing capabilities after experiencing combat-related trauma. Far and away, Dietsch said, the group members she worked with were young men who had sustained blast-related injuries or gunshot wounds. As they recovered from traumatic brain injuries, shrapnel damage and the like, they also couldn't eat.

"These are the guys who — let's face it, an 18- to 25-year-old population, if you brought in 10 Dominos pizzas and you turned to pay the delivery guy, all of the pizza would be gone by the time you turned back," she said. "To tell them, 'Hey, you've been overseas eating MREs for the last however many months you've been deployed, and now you are in delivery distance of 875 restaurants and you can't have any of it,' it does not go over well."

As a graduate student, Dietsch voluntarily went on an extended diet of pureed or otherwise viscous fluids in an effort to experience, as best as she could, the diet limitations many people with dysphagia endure. She can no longer stomach yogurt because of it.

"Pureed pepperoni pizza is not as bad as you would think," she said. "Pureed salad with Italian dressing is not good — for future reference."

At Walter Reed, she and two of her mentors, Nancy Pearl Solomon and Cathy Pelletier, who studies not only speech pathology but also has a Ph.D. in food sciences, wanted to motivate the wounded soldiers to continue through the rigors of dysphagia therapy. Dietsch said it grows frustrating not only for those who can't eat like they used to, but also for their loved ones who aren't sure how to adapt to the change.

"Family members don't want to exclude the person who's not able to eat safely, but they also feel weird about eating in front of them because that's just not how we do things," Dietsch said. "So people wanted to be part of the social aspect of it, and people also reported that they missed the sensation of tasting things."

Enter the taste strip. You may be familiar with Listerine's PocketPaks, which contain dissolving mouthwash strips. For a brief period, grocery stores offered them to shoppers as a way to sample a new flavor of sports drink, or tequila. Dietsch and the researchers used strips that they acquired from a now-defunct company to study whether or not if just a brief burst of flavor could help produce saliva in soldiers with dysphagia who also experienced chronic dry mouth. The results of the saliva study were promising, and the impact on morale was, too. Soldiers began clamoring for the taste strips, aside from the buttered popcorn-flavored ones.

"There were some that were vanilla cupcake," she said. "Glazed donuts were a big hit. The lemon-lime ones were really popular. We had bacon ones. There were people who loved them, and there were people who would like grab the trash can, which is kind of how real life is with bacon."

Dietsch, who grew up in Omaha, said she returned to Nebraska not because it's close to home, but because the facilities on campus — a neuroimaging center, a food science program and the speech pathology clinic among them — will help further her research on taste and sensory information and how it relates to swallowing. As she continues to research dysphagia, she said she also wants to offer those dealing with it safe reprieves from being unable to dine.

"For people who have a swallowing disorder, and aren't able to eat anything, the feedback is, 'I will take what I can get,'" she said.

After Bill Nielsen suffered a stroke in February, he said he had no idea his recovery would include a month of being unable to eat.

"They were telling me I would be better in a week," said Nielsen, who celebrated his 37th anniversary with his wife, Marie, at Madonna on Thursday. "And I probably would have been, if it weren't for all the other things."

"You just kept getting everything possible that could go wrong with you wrong," Marie Nielsen said.

He received treatment in Norfolk, his hometown, for four days before a case of pneumonia forced his transfer to the University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha. He couldn't eat or drink, and was fed through a tube inserted through his nose.

"And just bad luck, it pooled and created an ulcer," he said. "So I went a month without eating."

He rejected the concept of thickened water, opting instead for the syringe. At Madonna, Nielsen joined the dining group, and "graduated" within a week.

"I went from barely being able to eat anything to where I can chug a bottle of water now," Nielsen said. "It was huge. My wife and my sons came down on Easter and I had a Dairy Queen chicken strips basket with white gravy. I think the second day, I had a beef enchilada. I mean, it was not like a normal one, it was ground-up some. But it was. . it was awesome. It's amazing, stuff you wouldn't look at before, and how appetizing it became."

Nielsen said he planned to celebrate his wife's birthday on April 26 at their favorite Mexican restaurant.

___

Information from: Lincoln Journal Star, http://www.journalstar.com

An AP Member Exchange shared by the Lincoln Journal Star.

- Updated

MADISON, Wis. (AP) — Records show Wisconsin health officials waited several months to announce an outbreak of a rare bloodstream infection to the public, WBAY-TV reported.

Using records obtained under an open records request, WBAY (http://bit.ly/1VwuYP7 ) reported Friday that the Wisconsin Department of Health Services began investigating the outbreak of the bacteria known as Elizabethkingia in December and told hospitals and labs to be on the lookout for the infection in January, but waited to announce it to the public in March.

Eighteen deaths have been linked to Elizabethkingia in Wisconsin, and 59 cases have been confirmed in the state in the largest outbreak in the U.S. The state health department says it has not been determined if those deaths were caused by the infection or other serious pre-existing health problems.

Gov. Scott Walker said Friday that when the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and state health officials could not find the source of the outbreak on their own, they went to the public.

"They'd been working with individuals — patients and their families, and obviously with health care providers— so those individuals were aware of it. But when it was clear that CDC raised their concerns, then that's when they wanted it to be out to the public," Walker said.

In a statement, the Wisconsin Department of Health Services said it reacted quickly to the initial reports of a potential outbreak and launched an investigation to determine the cause, but wanted to avoid alarming the public.

"This outbreak has proven to be very unique and complex, and our disease detectives have yet to find the source of the bacteria, which limits the directives we can offer the public related to prevention," the department said. "This was a rare situation in which we recognized that releasing information without being able to offer any direction on how to avoid it, would inspire fear among the public."

The source of the outbreak remains unknown, but the department says there is no indication it was spread by a health care facility. Most of the infected patients are over 65 years old, and all have a history of at least one underlying serious illness. Symptoms include chills, shortness of breath and fever. The outbreak has primarily hit southern and southeastern Wisconsin.

Walker has announced the creation of nine new positions at the state Department of Health Services to combat the infection.

Information from: WBAY-TV, http://www.wbay.com

- Updated

GRANITE CITY, Ill. (AP) — Students in the southern Illinois town of Granite City will no longer be required to wear uniforms to school.

According to the Belleville News-Democrat (http://bit.ly/1SdL0at ), the local school board recently reversed a policy requiring uniforms.

That policy was put in place in 2009 and called for khakis and collared shirts.

Starting this fall students will be able to wear a wider variety of clothes, including jeans and T-shirts.

Superintendent Jim Greenwald said the uniform policy was sometimes needlessly strict. Some students were disciplined for wearing sweat shirts over polos, for instance.

And Greenwald said uniforms did little to help curb discipline issues or the bullying it was aimed at addressing.

Greenwald stressed the school still has a dress code.

Granite City is about 10 miles north of St. Louis.

___

Information from: Belleville News-Democrat, http://www.bnd.com

- Updated

CHICAGO (AP) — Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel has launched a new initiative to provide digital training and access to technology to city residents.

The mayor's office on Saturday announced the new Connect Chicago initiative.

Emanuel said in a written statement that the new program is intended to help strengthen the city's economy.

The program will expand the Chicago Public Library's CyberNavigator training and tutoring program from the current 48 library branches to almost all 80 branches.

Connect Chicago also plans to pay to double the size of the digital skills training programs now run by the Local Initiatives Support Corporation Chicago to train 1,000 people this year.

- Updated

POTWIN, Kan. (AP) — Joyce Vogelman Taylor couldn't quite explain why strangers kept calling or showing up at a property she owns in rural Kansas.

But she gained some clarity recently when the online site, Fusion.net, published an article about a Massachusetts-based company, MaxMind, which helps companies learn where their Internet traffic comes from. In its 2002 search for a middle-of-America spot for a U.S default IP address, and after consulting reference materials, MaxMind unknowingly selected the same geographic coordinates as Taylor's family home, which is rented out.

An IP address, which is akin to a physical address for computers, helps tell computers where to send information and where information is coming from. Sometimes MaxMind clients would want to know what state or city Internet traffic comes from. Others might want to know an exact house so, for example, they could send letters telling people to stop downloading illegal movies and music, The Wichita Eagle reported (http://j.mp/1MubV4G).

Because of the confusion over the IP address and the physical address, since 2011 people had been showing up at the Vogelman property claiming that the IP address for their complaints was associated with the property. Butler County Sheriff Kelly Herzet eventually had to post a sign on the edge of the property telling people there had been a mistake and to call the sheriff.

A Wichita Eagle reporter told Taylor on Monday about the Fusion article, which also said MaxMind would move the geographic location for its default IP address away from her property north of Potwin and to a body of water.

"Yay!" said Taylor, 82.

"I do not know anything about the Internet," she said. "I really don't. I just know about being harassed."

Jason Ketola, MaxMind's vice president of operations, said the company's data isn't "intended to be used to identify particular households." He also said the company has changed the location of that default IP address away from Taylor's property and is looking at changing other IP addresses that could cause similar problems. He also said the company intends to apologize to Taylor.

___

Information from: The Wichita (Kan.) Eagle, http://www.kansas.com

- Updated

KANSAS CITY, Mo. (AP) — Google has received permission to put antennas on Kansas City light poles and other structures to test new technology that could lead to citywide wireless connectivity.

The company that brought super-speed Internet to the metropolitan area on both sides of the state line four years ago is looking at whether it could use wireless technology to provide service to places where it's too expensive to bury cable or string it on utility poles.

If the emerging technology works in a city setting, it could make Kansas City the most wired and wireless place in the world to tap into the Internet, The Kansas City Star (http://bit.ly/1VuFNBl ) reported.

Google is hesitant to raise hopes of constant connectivity, however. The tests will operate in a radio spectrum that home computers, smartphones and tablets can't reach without installing new chips or antennas.

It's unclear whether the tests will work or how and when the broad wireless connections might be of use to consumers. Google estimates that it might understand what's possible by the end of next year.

At a Kansas City Council meeting Thursday, the company asked for two-year permission to install antennas in eight areas.

Robert Jystad, a Google consultant who presented the company's plan to the City Council, said the project is motivated partly by the inability of existing Wi-Fi and cell networks to keep up with fast-growing demand for bandwidth.

Council members voted 11-2 to give Google access to city light poles.

The targeted radio spectrum for decades could be used only by the U.S. military, and in practice it remained mostly vacant. Last year federal regulators opened it up in hopes that newly available frequencies might relieve the airwave congestion that makes connecting to the Internet on the go a hit-and-miss endeavor.

Google said it wants to operate in that spectrum experimentally in Kansas City. It's unclear how long it would take to attach its antennas to city light poles and inside buildings in the test areas, and Google said it doesn't know how long it will take to test the system.

The company has spent hundreds of millions of dollars to string fiber-optic lines on utility poles and underground in creating its Google Fiber service in the metropolitan area — the first region in the U.S. chosen for the 1 gigabit service.

Though it came under fire for skipping over neighborhoods where it found only middling demand for its high-speed offering, Google said it couldn't justify the expense of construction in those areas. The use of radio signals instead of expensive construction to extend cables might be a way for Google to shift that dynamic.

___

Information from: The Kansas City Star, http://www.kcstar.com

- Updated

OAMHA, Neb. (AP) — Omaha police say they have found a missing 5-year-old boy trapped under the seats of his parents' sports car.

Omaha television station KETV reports (http://bit.ly/1MzEuho ) that police were called to an area southwest of downtown Omaha just after 11 p.m. Friday. The boy's family told police they were eating at a restaurant when the boy said he was tired, and the parents let him sleep in the car.

Police say when the parents later returned to the car, they couldn't find the boy and called authorities. Officers ordered trains in the area to stop running while they searched. About an hour later, the boy was found stuck underneath the car's seats.

Police say the parents face child neglect charges.

___

Information from: KETV-TV, http://www.ketv.com

- Updated

DES MOINES, Iowa (AP) — Thousands of dollars donated to help an Iowa motorcyclist who lost a leg in a crash have been stolen. Now, the Des Moines motorcycle community is stepping up to help.

Des Moines television station KCCI reports (http://bit.ly/1MzDEBh ) that thieves stole more than $2,000 collected since last month to help 33-year-old Matt Brooks, who remains hospitalized following his March 17 crash.

Brooks' friend, Bruce Cronk, says the money was collected in jars and containers and taken to Brooks' mother's house, where she kept the money in a safe. Police say it was stolen by two people who kicked in the woman's back door on Friday.

Cronk and several friends are now selling T-shirts and preparing benefits to help raise more money for Brooks.

___

Information from: KCCI-TV, http://www.kcci.com

- Updated

BOWLING GREEN, Ohio (AP) — A state highway worker in northern Ohio made a slithering discovery.

The Ohio Department of Transportation worker in March found an aquarium lying on the side of the road with an 8-foot boa constrictor.

Buddy Malone tells WTOL-TV (http://bit.ly/1RZvkuz ) in Toledo that he brought the snake back to the highway department garage and they then contacted Bowling Green State University.

Biology professor Eileen Underwood says the workers likely saved the snake.

She says the boa, named "ODOT" by students, is doing great now. Underwood says the snake is a real sweetheart.

Officials don't know how the snake came to be abandoned.

- Updated

SPRINGFIELD, Ill. (AP) — Illinois drivers could be taxed by the mile under a new proposal that would involve the use of devices to track the distance motorists travel.

The proposal from state Senate President John Cullerton, D-Chicago, is in response to declining fuel tax revenues, which are used to fix Illinois' roads.

Cullerton says vehicles getting better mileage still wear on roads and there needs to be a better way for the state to collect taxes and fund repair work, the (Arlington Heights) Daily Herald (http://bit.ly/1YupwJZ ) reported.

"If all the cars were electric, there would be no money for the roads," Cullerton said.

Under the plan, drivers could choose one of two ways that a device monitors their mileage. Under one option, the device would specifically track where drivers go and not charge for travel on Illinois toll roads or outside the state. The other option would just track odometer readings.

Or, if drivers have privacy concerns, they could also opt to pay a 1.5-cent-per-mile tax on a base 30,000 miles traveled annually.

Cullerton said Illinois drivers would receive a refund for costs of gasoline taxes. Those taxes would be paid as usual by drivers not registered in Illinois.

State Sen. Matt Murphy, R-Palatine, said the proposal would bring big change when a stalemate remains over the state budget. He said he understands what Culleton intends and that it could be best to go through testing in a pilot program.

"This one will probably require a thorough vetting," he said.

The proposal from Cullerton would establish a commission to determine some of the plan's specifics.

___

Information from: Daily Herald, http://www.dailyherald.com

- By CINDY GONZALEZ Omaha World-Herald

- Updated

By CINDY GONZALEZ

Omaha World-Herald

OMAHA, Neb. (AP) — Headed to the nearby supermercado, Josh Strobel and his dog, Gucci, sauntered out of their revamped Park Avenue apartment building — the one that until its makeover a few years ago was shuttered and fraught with social ills.

The Omaha World-Herald (http://bit.ly/1S9q8RJ ) reports that the Idaho-born university student and bow-tied Yorkie strolled by the storefront mission that doles out daily counsel and discounted items.

They passed the man snoozing in a booth, and the expanded pharmacy that used to share the corner with Sheri's strip joint.

Before scooting to class, Strobel walked his furry friend around other neighborly spots, including the family-owned convenience store finally shedding its window security bars, and another batch of apartments set to transform into trendy market-rate housing.

Few would disagree that revitalization efforts of the past few years have boosted this inner-city pocket once considered a home of last resort.

But now InCommon Community Development is sounding an alarm, fearing that the influx of investment and wealthier "gentry" is starting to raise rents and push out poorer folks who had an established support network in the area of Leavenworth Street and Park Avenue.

Leaders of the nonprofit based along Park Avenue are hoping greater awareness will minimize potential downsides of gentrification — or a changing of the neighborhood's residents from poorer people to wealthier ones, with the attendant increases in rent and fancier services.

"It began as pure benefit," said InCommon Director Christian Gray, citing the shabby-to-chic transformation five years ago of the row of apartments where Strobel lives. "But as other developers and opportunities have shown themselves, it started to take more of a form of displacement."

Gray's concern spreads beyond Park Avenue — and into other aging Omaha neighborhoods joining the growing nationwide number of areas changing with the infusion of more affluent residents and economic development.

"Gentrification has come back to public consciousness as cities have benefited from population growth and redevelopment," said Stockton Williams of the Washington, D.C.-based Urban Land Institute. "It's happening probably with greater velocity and in more places in recent years."

A national analysis by Governing Magazine identified 12 Omaha census tracts (of about 135 in the city) as "gentrified" by accelerated shifts in housing values and education levels. That report, which was published last year and looked at years through 2013, didn't capture Omaha's more recent flurry of urban redevelopment.

Even without data, area neighborhood leaders point to obviously transformed enclaves in Little Italy just south of downtown, Benson and other midtown areas such as Blackstone.

Marked by architectural and urban charm, those older places tend to be close to the city's core where increasing numbers of millennials, merchants and baby boomers have flocked in recent years.

Fueling the midtown draw is job creation at the University of Nebraska Medical Center campus and commercial activity at the $365 million Midtown Crossing campus built six years ago by Mutual of Omaha.

To be sure, experts say, the changing of the guard that accompanies gentrification isn't on its face negative: Who doesn't want a distressed area re-energized with fresh workers and a higher tax base?

But forcing residents to uproot risks further segregation and resentment that can fester into unproductive behavior, said Omaha Public Schools board member Tony Vargas, who before coming to town taught low-income students in Brooklyn areas dramatically altered by high-rent condos and businesses of that New York City borough.

The original character and fabric of gentrified neighborhoods also can suffer if longtime artists, merchants and tenants are priced out with soaring property values, said David Harris, a New York community development official who moved six years ago to the Omaha area.

InCommon worries about the shuffling around of disadvantaged families like those it is trying to reach through education and social programs based at its facility on Park Avenue near Woolworth Street.

"We don't do ourselves any favors by pushing poverty from one neighborhood to the next," InCommon's Gray said.

So far in Omaha, any adverse effects of gentrification have been relatively minimal, certainly not to the proportions seen in areas of Brooklyn, Portland or Chicago, says Robert Blair, an urban studies expert at the University of Nebraska at Omaha.

"I don't know where the break point is," he said. "It's a subtle sort of thing that takes place over a period of time. That is why monitoring is so important."

David Levy, a lawyer who serves on the governing boards of the Omaha Housing Authority and Omaha By Design, worked previously as a land use lawyer in San Francisco, where he saw more severe housing constraints. Displacement locally should be watched, he said, but added that he can't see Omaha's urban revival as "anything but a good thing."

InCommon leaders have started to talk to groups and city officials about ways to guide gentrification and form partnerships so people of all socioeconomic levels win.

Gray said he's unsure what has happened to midtown residents who over the last few years left homes that were torn down or completely renovated. No one has kept track. Gray said he knows at least one client who landed in a shelter and can't help but wonder the fate of others.

Meanwhile, InCommon has put money where its mouth is, buying the century-old Bristol Apartments on Park Avenue before a private developer could. The goal: to keep the 64 units at about $450 a month, as rents around it often have doubled that amount.

City planners agree with InCommon that a mix of income levels could be ideal for neighborhoods, but don't necessarily agree that city government should intervene.

The dominant tool the city now uses for urban redevelopment is tax-increment financing. Gray suggested, for instance, that developers receiving such a financial break could set aside a certain number of units for lower-income tenants.

Planning Director James Thele said TIF fills the financial gap needed to pull off infill projects. He said adding more mandates likely would torpedo many of those efforts.

Furthermore, Thele said, he doesn't see a problem at this point with gentrifying neighborhoods. Most of the redevelopment of urban areas, he said, has involved decaying or vacant structures and empty lots.

"Should these deteriorating properties be kept in that state so rent stays low?" asked Thele. "That doesn't make any sense to me."

Thele said he has not seen "substantial" displacement, though he acknowledges that no one has kept a tally.

Rather than messing with a free market, Thele said he believes the best route to maintaining affordable rents in gentrified areas is with initiatives such as InCommon's Bristol.

The dwindling pot of money Omaha has available for low-income housing is focused on certain north and South Omaha blocks that aren't attracting private investors, said David Thomas, who directs the city's Housing and Community Development division.

The idea is to instill hope in the future of those residential pockets, and ultimately draw more outside dollars.

Thomas noted that, on the other hand, private developers today aren't needing much prodding to enter areas such as Park Avenue, Little Italy and Blackstone.

Since 2013, for example, public records show that Harvest Development (also known as HD) paid $1.3 million for eight mostly multifamily properties along a few-block stretch of Park Avenue north of Woolworth Avenue.

"We see it as revitalization," said Bret Cain, the company's vice president of operations. "We're very happy with how things are going."

Cain declined to disclose how much the company has put into rehabbing. Harvest didn't seek public financing on those Park Avenue structures that would have revealed such detail. The firm's midtown rents range from $700 to $1,800.?"Naturally, you get a few unhappy with the rent increase," Cain said. He said the community trade-off is updated housing with green space.

Harvest is about to open the new Ekard Court at 617 S. 31st St., where 27 beat-up apartments once were. That $3.6 million project, which brings 36 luxury apartments, was assisted by city-approved tax-increment financing.

While Harvest has revived properties elsewhere in the city, its recent purchase of an old Park Avenue laundromat for a headquarters portends continued focus in transforming midtown buildings into market-rate apartments.

It is not alone.

Private developers including Milestone Property, Bluestone Development and Uptown Urban Dwellings have jumped on the multimillion-dollar midtown redevelopment bandwagon. Urban Village Development, a pioneer in the Park Avenue area, continues to grow its inventory.

Farther west, nearer the medical center campus, GreenSlate and Clarity Development companies have led more than $40 million in investment in the once-bleak Blackstone business district.

That momentum started with retail revival and shifted to housing. Their latest venture calls for transformation of the Colonial Hotel at 38th and Farnam Streets, which most recently was a worn boarding house charging $100-a-week rents.

The plan is to return the century-old property to its roots as a fancy Renaissance Revival-style apartment structure. In doing so, monthly rents are to rise to between $850 and $1,400.

Clarity's Mike Peter, who also is on the governing board of InCommon, said Omaha's urban conversion projects, including the Colonial, have been obsolete properties crying out for change.

A solution that doesn't compromise revitalization, yet secures families, is creation of more affordable housing options in and around the transformation. Omaha, he said, is in a better position to do that than coastal cities that face land shortage and extreme rent-income disparities.

"What people want is better housing; they don't want to just live in a certain place."

Helpful tools to create affordable housing include a proposed state low-income housing tax credit program under consideration in the Nebraska Legislature, said Clarity's Tom McLeay. He said it makes better sense financially to slip in separate affordable rental housing in reviving neighborhoods than to require private developers to put low-income units in a newly renovated building.

From InCommon's view, not all developers have been willing to work with it to ease negative effects of transformation.

Interviews with area residents show plenty of work ahead in blending the two income worlds on Park Avenue.

Strobel, the Creighton University student who has lived on the corridor since last year, likes the proximity to campus. He likes the dog-friendly landlord, the interior of his revamped Art Decos unit. He fully supports the street ministry next door.

But the 23-year-old pre-med student is weirded out enough by what goes on outside after dark that he prefers his wife, Alexsandra, not walk the dog alone. He said the yelling and commotion stems from people he doesn't recognize.

And he's moving after graduation.

"It can get scary," he said. "I don't see it as somewhere I'd like to be long-term."

Kristie Eisenauer, who lives in a lesser-income apartment south of Art Decos, describes her street as two different worlds. She can't believe the rents. "I mean, they're trying to make this Beverly Hills."

Mary Ann Caniglia has outstayed most on Park Avenue. And though she considers many of the old guard her family, she appreciates changes that have pushed out bad elements.

Her family-owned Park Avenue grocery is making its own shifts — adding deli sandwiches and Blue Moon to the lineup of generic beers. Caniglia, her husband and children also are removing security bars from their store windows "so we can see the progress."

Said Caniglia: "We're excited about another phase to Park Avenue."

___

Information from: Omaha World-Herald, http://www.omaha.com

An AP Member Exchange shared by the Omaha World-Herald.

- By HANNAH SPARLING The Cincinnati Enquirer

- Updated

By HANNAH SPARLING

The Cincinnati Enquirer

CINCINNATI (AP) — The month of cauliflower was weird. Like, 'What do we do with all this cauliflower?' weird. They made soup.

Then, there were the radishes. So. Many. Radishes. They turned them into soup.

Chef Suzy DeYoung and her "Bucket Brigade" of local chefs are on a mission: Use donated produce to make soup. Use soup to save the city.

Sort of.

"We've got to start somewhere," said DeYoung, 57. "So if we start with food — the basic necessity of food — the schools have a better chance of doing their job."

It's called La Soupe (that's "süp," not "sü-PAY") and here is how it works: Stores such as Kroger and Jungle Jim's donate produce they would otherwise throw away, and DeYoung and a team of volunteer chefs turn it into soup. Then, they give that soup — or, sometimes, stew or gumbo or casserole — to people who are hungry.

It's shameful, DeYoung said, how much food gets thrown away while so many go hungry. According to the United Nations Environment Programme, somewhere between 30 percent and 40 percent of the food supply in the U.S. is wasted — more than 20 pounds per person per month.

Globally, one of every four calories never gets eaten.

DeYoung does what she can. La Soupe collects about 4,000 pounds of produce a month. There are more than 60 volunteers who haul soup and produce to and fro, from stores to chefs to hungry mouths.

Soup is delivered to five schools every Friday and to another six or seven schools and churches during the week. DeYoung also hosts cooking classes at Oyler School, DePaul Cristo Rey High School and John P. Parker School. Soon, she's launching another class at Child Focus in Mount Washington.

La Soupe started about three years ago, and it's a model that's learning as it grows. Where are the best schools to host classes? What recipes are good to share, easy for young students to recreate with what they have at home? What is the best way to bring onboard more chefs, get more donations, attract more volunteers?

Education is priority No. 1, DeYoung said; it's the best shot at a better life for Cincinnati's children. "But if you can't learn because you're not eating, the answer has to be in the food."

DeYoung uses words like "rescued" and "saved" when she talks about produce. Fire and police stations are safe houses for babies, she said; La Soupe is the safe house for fruits and vegetables.

"We're the last stop," she said. "If it hits us and it's usable, we use it."

If it's not usable, DeYoung passes it on to pig farmers down the road. She doesn't want to preach, but she does want change — she wants people to see food how she sees it.

"I never looked at it as disposable," she says.

DeYoung grew up in Mount Lookout. Her father, Pierre Adrian, was head chef at the Maisonette in Cincinnati, and her grandparents were chefs in New York. DeYoung and her sister co-ran La Petite Pierre in Madeira until DeYoung split off to focus on La Soupe.

She was born to be a chef. And she's still a chef, but now, she's a teacher, transportation manager and beggar, too. She hates asking for money — "It's so uncomfortable," she said — but she hates even more the thought of doing nothing. And to change how a generation eats? That's expensive.

Cincinnati is speckled with food deserts on the United States Department of Agriculture's map. USDA defines a food desert as an area where residents are low-income and have little access to healthy food. There are dozens of deserts in the I-275 loop.

For its population, Cincinnati needs 10 more grocery stores to catch up with the national average, said Renee Mahaffey Harris, chief operating officer of the Avondale-based Center for Closing the Health Gap. Without a nearby grocer — and without a car to get to one farther away — people turn to convenience stores, where options are limited and less-healthy.

Good food is but one in a long list of necessities, Harris said, but it truly is life and death. In 2010, Cincinnati had 1,400 diet-related deaths, she said — deaths from diseases attributable, at least in part, to food. That includes diabetes, stroke and heart disease.

"That does tell you, we have a lot of work to do," Harris said, "because what you eat does affect your overall health."

"Hello, everyone! I'm Suzy."

DeYoung is standing in the cafeteria at John P. Parker elementary in Madisonville. It's evening. Class let out hours ago, but the building is still bustling. Students race around the gym playing basketball. In the cafeteria, parents huddle around tables with their young children, taste-testing soup and listening to DeYoung.

She shares the "secret" to seasoning food. She teaches the children how to chop and peel vegetables, then she lets them practice on piles of produce.

On one corner of the stage, there's a stack of new slow-cooker Crock-Pots that will be given away. That practice started after DeYoung realized how many families are lacking basic cooking resources.

John P. Parker is a relatively small school — 263 students at last count. It's about 95 percent economically disadvantaged, a measure that looks at how many students qualify for free or reduced-price lunches. It's the sort of school, said 38-year-old Be Madison, a parent volunteer, where a free meal on Fridays can make a big difference.

It's a "sigh of relief" for parents, Madison said, "to know they're not going to have to worry about dinner."

Madison is trying to change how she shops and cooks, she said. It's a learning process. And she's learning a lot from La Soupe. It turns out it's pretty easy to stick to a budget, she said — "once you eliminate hot Cheetos and Kool-Aid."

"You can't do something you've never been taught," she said. ". If we can teach parents how to feed the kids, then the kids will know how to feed their children."

As the tri-state emerges from the recession and more people land jobs, one side effect is they get kicked out of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, commonly known as food stamps, said Freestore Foodbank President/CEO Kurt Reiber. In the past, the freestore would serve roughly 8 million meals a year, Reiber said. This year, it's on track for 23 million.

The goal is to get people to self-sufficiency, Reiber said, where they can shop, cook and eat well on their own. He's glad programs like La Soupe are drawing attention to the issue and fighting for change.

DeYoung's father died in middle age, and she started her first restaurant, in part, to carry on his legacy. He was a great chef who didn't get to cook long enough, she said.

With La Soupe, though, she started it because she didn't have a choice. She couldn't help it. She couldn't stop thinking about how much food gets thrown away.

And while there are a lot of programs that focus on food, she likes her model because it leans on chefs.

The challenge, said Orchids at Palm Court Executive Chef Todd Kelly, is using vegetables — "icky" vegetables — to make food kids will like. La Soupe drops off produce once a week at Orchids, Kelly said, and it's like a puzzle figuring out what to create.

Once, it was about 50 pounds of potatoes and a dozen stalks of celery, Kelly said. Another week, it was artichokes and cardoons. Those fiber-heavy thistles are great, Kelly said; "I absolutely love them. . But it's not exactly a fan favorite, where kids are going, 'Woo! Cardoons!.'"

Kelly committed to La Soupe about six or eights months ago. Orchids included, the Bucket Brigade is now 19 members strong.

"It's not going to solve world hunger," Kelly said, "but it's definitely going to help do a dent."

La Soupe has a café location on Round Bottom Road near Newtown. It's French, but it's on a rural street in eastern Cincinnati. The next street over is dubbed "Heroin Alley" for the number of overdose victims it sees. La Soupe's slogan is "A French Roadside Soup Shack," words not often stuck together.

It's closed on Mondays. But, frankly, La Soupe is not very good at being closed. Shortly before noon one Monday, an order came in for seven croque monsieur sandwiches and as many soups. OK. Then, it was a steady line of customers — some regulars stopping by to chat; a hungry couple out for a walk with their horse-sized dog; a girl, weary of sandwiches for lunch, who heard about La Soupe through a friend.

It's always like that, DeYoung said. Always busy. Always running. Always brainstorming the next big idea.

In Lower Price Hill one day, she and a few La Soupe volunteers are teaching some Oyler High School students how to make cookies. Several are perplexed by the mixer. They've never seen one before.

That's the reality, DeYoung said. A lot of the students she meets don't have an oven at home. One girl said her family doesn't have a fridge.

The Oyler cooking class was DeYoung's first, and it meets every Monday after school. Each student has a Crock-Pot now, and when DeYoung teaches a recipe, she sends everyone home with enough ingredients to replicate it for six people. That way, they can go home and cook for their families.

One Monday, they learned how to make Crock-Pot lasagna. Another, it was chicken cacciatore. Junior Chris Lewis was there. He loves the cooking class because it gives him a reason to show up for school.

"You know how Mondays are," he said.

Lewis, 18, wants to be a chef once he graduates, and in fact, he's starting an apprenticeship this summer with Cincinnati chef Jean-Robert de Cavel. That's the result of connections Lewis made through DeYoung and La Soupe.

DeYoung loves Lewis' story, because chefs are always bellyaching about how they can't find quality employees. Well, here's the answer, she said: They can volunteer with La Soupe, teach cooking classes, and find and train their own future chefs.

Problem(s) solved.

___

Information from: The Cincinnati Enquirer, http://www.enquirer.com

- By LAUREN SLAVEN The Herald-Times

- Updated

By LAUREN SLAVEN

The Herald-Times

BLOOMINGTON, Ind. (AP) — Rainy days weren't fun at Possum Hollow farm.

"It was really muddy when it rained," Mary Dolan remembers. "It was terrible."

Dolan spent her childhood summers at the farm near Washington, Indiana. Her aunt raised chickens just like the ones Cheryl Shireman raises on Shireman Homestead farm in Columbus.

A recent afternoon was rainy, but 91-year-old Dolan had the chance to make a happier, drier barnyard memory at Cambridge Square Apartments in Bloomington.

Shireman carried Henny Penny swaddled in a blanket to keep the orange chicken warm as she walked the hen around a room of seniors gathered in Cambridge Square's common area. Dolan and other apartment residents stroked Henny Penny's feathers and asked Shireman questions about chickens' lifespans and egg-laying behaviors.

Asked one resident: Does Henny Penny like being carried around like any other pet?

"She's tickled pink," Shireman replied, and the seniors laughed. "How would you like somebody to pick you up and carry you around all day?"

The apartment complex is mostly home to seniors older than 62 who can live independently. No matter their ages, almost all the Cambridge Square residents who fawned over Henny Penny could recall a childhood memory about living on a farm or working on a farm.

"When they're gone, those stories are gone," Shireman said. "If we listen to the stories of the past, they have so many things to share."

Shireman remembers as a young girl visiting nursing homes to perform with the other kids in her tap, jazz and ballet dancing classes. The seniors loved having visitors, and Shireman loved the feeling of making someone's day.

"It dawned on me as I got older . oh my gosh, some of these people don't have a family anymore," Shireman said.

Shireman has spent the past nine years growing her farm and nonprofit, Shireman Homestead, where she rehabilitates farm animals and holds educational events. Shireman's newest enterprise has been transporting the farm's chickens, ducks, miniature horses, teacup piglets, rabbits and other animals to schools and nursing homes to interact with students and seniors.

"Animals can be so therapeutic," Shireman said. "Animals have unconditional love."

In the second week of May, National Nursing Home Week, Shireman hopes to bring animals such as Blossom the donkey, Tiny the pygmy goat and Henny Penny to at least 50 nursing homes and assisted-living facilities across the area.

"I think it definitely boosts the mood," said Kristine Sills, service coordinator for Cambridge Square Apartments, who invited Shireman and her animals to visit the residents.

By the time they reach a nursing home, a senior may have few family members or dependable resources nearby, Shireman said. And some of the elderly men and women she's visited have a lifetime of memories about dealing with difficult people.

Neither Blossom, a 3-month-old donkey with hooves painted with sparkly pink nail polish, nor Lucky, a white Pekin duck, had a cross word for the Cambridge Square residents. The barnyard critters were happy to let seniors such as Carolyn Pelfree pet and coo over them and reminisce.

"I love all animals," Pelfree said. "If we saw an animal that's not got a home, my dad would take it in."

Shireman, who also grew up on a farm, collects these stories and makes stories of her own on the road. Elderly people with disabilities open up around Shireman's animals, she said, often to the surprise of their nurses.

"This is the most exciting time of my day, when I come to visit," Shireman told the seniors. "You make my day, being able to visit you."

___

Source: The (Bloomington) Herald-Times, http://bit.ly/1Vq8CyQ

___

Information from: The Herald Times, http://www.heraldtimesonline.com

This is an AP-Indiana Exchange story offered by The (Bloomington) Herald-Times.

- By RYAN LOHMAN South Bend Tribune

- Updated

SOUTH BEND, Ind. (AP) — Desperate for money to keep the lights on and provide her daughter with a few gifts last Christmas, Patricia Patterson turned to short-term lending.

She had been there before. Patterson, 42, a South Bend native, took out a payday loan to make ends meet a few years ago when she lived in Nashville, Tenn., she said. That didn't end well for her.

"It hurt my credit when they sent it to collections," Patterson said, still upset from the experience of falling behind on payments to a payday lender.

Her second time around with a short-term loan was much different. Patterson took out the loan last December in South Bend from a lender she calls the "JIFFI boys."

"The JIFFI boys didn't do anything like that," she said, mentioning the low interest rates and lack of "harassing phone calls" that marked her first experience.

JIFFI is the Jubilee Initiative for Financial Inclusion, a nonprofit started in 2013 by Notre Dame finance student Peter Woo as a way to combat what he saw as predatory lending in South Bend.

The JIFFI boys Patterson talks of are Jack Markwalter, JIFFI CEO, and company. All of JIFFI's employees, some of whom are women, are students at the University of Notre Dame or Saint Mary's College. Patterson happened to have worked only with men from the organization, hence, "JIFFI boys."

"I didn't know we had that nickname," Markwalter said. "That really speaks to the personal relationship we have with our clients that differentiates us from traditional payday lenders."

JIFFI offers an alternative to services such as the one Patterson dealt with in Nashville. That's the biggest component of its mission, "to create a financially inclusive environment in the South Bend community," Markwalter said.

What that looks like currently is offering short-term loans with low interest and flexible payments, and financial literacy education. Now in its third year, Markwalter said he wants to see JIFFI expand to take on new clients and bring in more money to lend.

The money JIFFI lends comes largely from donations and grants, but JIFFI, a nonprofit, still charges interest on loans it makes. The company sets the interest rate far below those of payday lenders, Markwalter said, and considers it an opportunity for borrowers to learn about how interest works so that when clients need to take out a loan from a bank, they will be familiar with the terms.

"We don't think it makes a huge dent in what they end up paying us when they pay the loan back. The average is about $9 interest," Markwalter said.

Compare that with payday lenders, which in Indiana can charge a 391 annual percentage rate. But even with such poor terms for the borrower, Markwalter said, he understands why payday loans are so popular.

"The most attractive thing about a payday loan is that instant access to cash," Markwalter said. "Most people who go into taking a payday loan are either behind on some of their bills, or they had something that threw them out of financial equilibrium."

For JIFFI clients, that can often mean a car breaking down, preventing them from getting to work and earning money, Markwalter said. For these clients, losing a job isn't an option. So they turn to what is often their only source of quick cash available: payday loans.

"But it comes at a high price tag, and that's the high interest rates," Markwalter added.

The reliance on such high interest, short-term loans to resolve emergency money needs creates a cycle that can be hard to escape, said Vincent Vangaever, JIFFI vice president of financial empowerment.

"(The loan) is very short term — usually a period of 10 days to two weeks where you're required to pay back the entire principle in addition to the interest," Vangaever said. "If an individual doesn't have $500 today, why are they going to have $550 in two weeks?"

JIFFI loans have always come with an element of financial education attached, Vangaever said. But JIFFI has expanded to offer financial empowerment courses to kids and also adults regardless of whether they aim to take a JIFFI loan. They see it as another way to achieve their mission.

"In the beginning, it's very, very basic, explaining what a budget is, how you can save — these really important lessons that a lot of students aren't taught in schools," Vangaever said.

Along with adding the classes, JIFFI has also grown significantly in its three years, now employing 40 students. In 2013, JIFFI made three loans to clients in South Bend. Now Markwalter said JIFFI has made 32 loans, but wants to grow bigger still and increase that number by directly reaching those who need their services.

Most of their clients hear about JIFFI through charity organizations. Bridges Out of Poverty, for instance, connected Patterson to the loan program.

Amber Werner of Bridges Out of Poverty said she is glad to connect those in need to JIFFI. "It's a fine opportunity for people in South Bend to break the cycle of living with payday loans and to learn and understand the importance of credit," Werner said.

But those who wish to apply can reach out to JIFFI directly, Markwalter said. Then they can fill out an application.

Like any other lending institution, JIFFI does expect to be paid back. But in this, too, it differs from the terms of a payday loan, Patterson said.

"I kept communications open with them. If there came a time I couldn't pay them, I called them, and they were fine with that. There was only time that it happened."

But in the end, Patterson did end up paying off her loan from the "JIFFI boys."

"My last payment was on February 13th, which was my birthday," she said. "I would never go to another payday loan place."

___

Source: South Bend Tribune, http://bit.ly/20zwNdd

___

Information from: South Bend Tribune, http://www.southbendtribune.com

This is an AP-Indiana Exchange story offered by the South Bend Tribune.

- By LEANN BURKE The Herald

- Updated

By LEANN BURKE

The Herald

ST. MEINRAD, Ind. (AP) — Some monks brew beer or cobble shoes. Brother Simon Herrmann keeps bees.

The 28-year-old monk took over the St. Meinrad Archabbey's hive last year when he began his three years as a junior monk at the monastery in Spencer County. Each monk has his own job to do to help support the community, and generally the superiors — leaders of the monks — want the brothers to come up with their own work. That way, Herrmann said, they know the monks will be interested in what they're doing.

Beekeeping is traditionally a monastic practice, so when Herrmann asked to take over the hive, the superiors were happy to oblige. Herrmann's family, which lives in Oxford, Ohio, were supportive as well.

"My brother was like, 'Yeah, didn't you know Dad used to keep bees?" Herrmann said. "And I was like, 'Really? Cool."

Herrmann grew up in Ohio and first came to St. Meinrad as a high school student participating in One Bread, One Cup, a ministry of the archabbey. While in college at the University of Dayton, he returned to the abbey as an intern, and he took a job at the abbey a few years after graduation. He became interested in monastic life during his internship, but he "had some growing up to do" and didn't decide to pursue monasticism until he took a job in the development office.

"That allowed me to have even a closer experience with the monastery praying with the monks and going to Mass almost every day before work," Herrmann said. "(So far,) it's been great."

Herrmann is one year into his temporary vows, which last three years and come before the solemn vows that tie a monk to monasticism and a single monastery for life. He's also one year into this tenure as the monastery's beekeeper. Before Herrmann took over, Father Anthony Vinson took care of the abbey's single hive, down from the eight or nine Herrmann was told once lived on the property. Vinson had several other tasks at the monastery, however, so he was happy to pass the bees off to Herrmann. Vinson hasn't totally abandoned the bees. Herrmann often goes to Vinson with questions, and Vinson will remind Herrmann of tasks coming up with the bees when they run into each other in the lunch line.

Overall, beekeeping isn't a labor-intensive job, Herrmann said.

"I used to take care of our chickens here ... and that's a daily thing," Herrmann said. "It's a very brief, like 10-minute daily thing where you go in and collect the eggs and top off their water. But with the bees, there are certain times of the year when it's more involved."

Most of the work comes during the changing seasons. In the spring and fall, beekeepers have to prepare the hives for the shift in weather. In the spring, Herrmann removes the mouse guard, which keeps rodents from getting into the hive and eating the comb and honey the bees rely on for food, and checks on the bees to make sure they're healthy and that not too many died off during the winter. In the fall, Herrmann attaches the mouse guard and removes the honey. There's no set time for honey collection. It all depends on the weather and when the bees become less active. To know when to collect honey, a beekeeper must watch his bees.

"I think the most stressful and the most hectic (time) I experienced last year, and I think because it was new, was actually getting the honey," Herrmann said.

Last year, Herrmann enlisted the help of novice monk Tony Wolniakowski to collect the honey. Neither of them knew what to do. Herrmann remembers the two just standing and staring at the hive for 10 minutes trying to figure out what to do. Eventually, they figured out a system.

To collect honey, the beekeeper removes the frames from the supers — the smaller boxes on the top of the hives — brushes the bees off the comb with a special, soft-bristled brush and cracks open the wax. Then, the frames go into a honey barrel that spins and forces the honey out of the comb. Herrmann's honey barrel is powered by a hand crank. Last year, Herrmann collected three gallons of honey. This year, he'll get more. He added two more hives just after Easter.

The monastery had all the supplies for the hives; the monks just needed the bees. Two packages each containing a queen bee and a few pounds of bees arrived in the archabbey's mail room the week after Easter for Herrmann to pour into the hives.

Herrmann thought about quitting the bees more than once last year during the hours of research, YouTube videos and not knowing what he was doing. But he kept at it.

"It was kind of like a lesson in monasticism," Herrmann said. "This is potentially where I might be living the rest of my life, and so this kind of simple lesson in beekeeping helped me as a monk because if I want to give up on this, what else am I going to give up on? ... But now that I have stood my ground with beekeeping and learned more about it and worked with other people to learn more about it and understand it better, I can see how cool of a hobby it will become."

___

Source: The (Jasper) Herald, http://bit.ly/1MuSTLG

___

Information from: The Herald, http://www.dcherald.com

This is an AP-Indiana Exchange story offered by The (Jasper) Herald.

- By NICK HYTREK Sioux City Journal

By NICK HYTREK

Sioux City Journal

SIOUX CITY, Iowa (AP) — Each morning when Floyd Food & Fuel opens, a worker walks outside to take a look at the six gas pumps.

"We go out every day and check, open the covers to see if they've been tampered with," said Terri Carlson, manager of the store.

Tampering may be a sign that someone has installed a credit card skimmer inside the pump. The small electronic devices read information from customers' debit or credit cards, and criminals then use that information to create new cards to make fraudulent purchases on the owner's account.

"They open the door to the pump and attach it to the wiring inside so you never see it," said Sgt. Chris Groves, of the Sioux City Police Department's investigations bureau. "You or I don't know until we start seeing charges on our credit cards."

The Sioux City Journal (http://bit.ly/1SNnHnw ) reports that Skimmers have been found in three gas pumps in Sioux City in the past six weeks, most recently at the Cenex station at 1800 Highway 75 North on Tuesday. Other skimmers were found in late February at Cubby's and Select Mart in late March.

When a customer inserts a card into the skimmer, his or her account information is swiped and stored on the device, which criminals later retrieve or access remotely through a wireless device in order to download the information. Groves said the skimmers found in Sioux City all were the type that must be retrieved.

Unlike ATM skimmers, which are installed to the exterior of the machine, gas pump skimmers are installed in the pump's interior, usually inside the panel that houses the card reader and receipt printer. It's a panel that workers must access to change paper and is usually not sealed with a fuel pump inspector's security label. Inspectors check the pump's measuring accuracy by accessing a different panel, Groves said, then seal that panel.

Unless you see someone install the skimmer, it's hard to determine who put it there, Groves said, so police are encouraging gas companies and owners of gas stations and convenience stores to take extra steps to ensure security at their pumps.

"We would encourage all owners to do something to prevent unauthorized persons' access to the machine," Groves said.

Store owners are increasing their vigilance.

Ahson Alahi, who owns the four Select Mart stores in Sioux City, said workers inspect the pumps daily for signs of tampering. Extra locks have been added to pumps, but someone somehow unlocked the pump at the Gordon Drive store to install a skimmer. Alahi said that pump would not work the next morning, and the skimmer was found by police who were called to investigate. No data from customer cards had been downloaded onto the skimmer, he said.

Alahi said he has installed new pumps that are harder to tamper with at two of his stores, and the older pumps will eventually be replaced at his other two stores. Store employees continue to keep a close watch on the pumps through store windows and on surveillance camera monitors.

"We're watching. If somebody's playing with the pump, an employee would notice it," Alahi said, though he added that three of his stores are closed overnight.

At least one larger company has implemented additional security to try to discourage pump tampering.

Kristie Bell, director of communications of Kum & Go, a West Des Moines-based company that operates more than 430 stores in 11 states, including 10 in Sioux City and the metro area, said the company in 2014 began placing security labels on gas pump panels housing the receipt printer and card reader. Workers check pumps daily to see if the labels or pumps show any signs of tampering.

"If it appears to have been tampered with, we shut down the pump and have it inspected," Bell said.

The Iowa Department of Agriculture and Land Stewardship's Weights and Measures Bureau inspect gas pumps annually, and inspectors have begun checking pumps for skimmers during the inspection, department communications director Dustin VandeHoef said. Inspectors have found a couple skimmers, including one of those in Sioux City.

"It's kind of a new focus for us," VandeHoef said.

___

Information from: Sioux City Journal, http://www.siouxcityjournal.com

An AP Member Exchange shared by the Sioux City Journal

- By CORY MATTESON Lincoln Journal Star

LINCOLN, Neb. (AP) — For the past 44 years, Terry Scott has been, as he described it, "one of them nasty ol' truck drivers." The Gretna resident did runs out to Cheyenne and back three times a week up until Valentine's Day this year. He was on mandated rest in Cheyenne that night when the phone rang.

"He jumped out of bed to answer the phone, and he fell on the floor," his wife, Debra, told the Lincoln Journal Star (http://bit.ly/1S9tfsC ).

Scott had suffered a stroke. The trucker was air-lifted early Feb. 15 from Cheyenne's hospital to one in Denver, where he spent 10 days in intensive care and a little over two weeks total before he could return closer to home.

On Wednesday, his vigorous handshake betrayed the Madonna Rehabilitation Hospital medical bracelet on his right wrist. An underlined message on the dry-erase board in his room announced his scheduled discharge date, April 13. It was lunchtime, and Scott was deliberately eating a French dip sandwich that had been ground into a coarse puree, soft carrots and an extra side of gravy. He drank grape juice and milk, both thickened with a honey-based solution in an effort to prevent it from going down the wrong pipe.

Eleven years ago, he said between bites, he went through radiation treatment for larynx cancer. So he knew from experience, as his body slowly regained strength, that he'd have to relearn things that once felt automatic, even something as simple as swallowing.

But swallowing, it turns out, isn't so simple.

"Swallowing is the single-most complex system in the human body," said Angela Dietsch, who teaches the graduate-level swallowing disorders class at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. "It involves 26 pairs of muscles, five cranial nerves and a 1.5-second process. How's that for intimidating?"

It's a process that often breaks down in patients seeking care for strokes, traumatic brain injuries, throat cancer and brain cancer. A symptom of a swallowing disorder — feeling like food is often stuck in your throat, gagging or coughing regularly — can be a precursor to a diagnosis of a degenerative disorder such as Parkinson's, muscular dystrophy or ALS. The muscles required to swallow can atrophy even more during the time a patient spends connected to a feeding tube.

"Most people don't even know there's such a thing as a swallowing disorder until somebody they care about has one," said Dietsch, an assistant professor in the department of special education and communication disorders at UNL. "But if you were to sit in Denny's on a Tuesday night or wherever and just start listening to how many people cough or clear their throats while they're eating, it's a lot of people. Which is not to say that all of them have a swallowing disorder, but it definitely starts to raise your alertness to the fact that it doesn't take much for that process to go haywire."

There is a name for the condition when the process has gone haywire — dysphagia. Because it often affects people who are undergoing treatment for life-or-death conditions, correcting a swallowing disorder was often an afterthought at best. But more and more, therapists and researchers are focusing on dysphagia.

"I can't imagine — even with as much time as I have spent working with people who have these kinds of issues, and sitting around the table with these people and their families -- I cannot even begin to imagine what it would be like to have that whole section of what is enjoyable of life be no longer a part of things," Dietsch said. "As cool as I think all of the science about it is, that's what makes me continue to work on it."

At Madonna Rehabilitation Hospital, patients being treated for dysphagia spend time in dining groups, where therapists monitor their swallows, said Teresa Springer, a Madonna speech-language pathologist who also teaches at UNL. She and other pathologists routinely study X-ray videos of patients who eat or drink solutions coated with barium, to follow the trail of food through, ideally, the esophagus.

And they also work the patients hard, said Terry Scott. The therapists drill into you a method for an activity you never thought about -- chin down, small bite, two swallows, small sip of liquid to wash it all down. Therapy methods can involve everything from muscle-stimulating electrodes to sipping air through straws twisted into knots. Madonna's patients with dysphagia are among the most vocal, Wagner said. Pronouncing words that include Ks and hard Gs work the muscles at the back of the tongue. Belting out an "E'' sound in falsetto can strengthen muscles used to swallow.

"Sometimes, our patients are loud," she said.

"Sit in here and sound like a little songbird," Terry Scott said.

"And that's kind of the new thing now, is we want our patients while they're going through radiation to keep working on their exercises," Springer said. "So we teach them their exercises before they go to radiation, so they're not losing as much muscle mass. It's kind of like, if you don't use it, you lose it. And so that's what they're learning now. That's what research is showing."

Scott said that when he went through treatment for cancer, he lost the ability to swallow for four months.

"They didn't offer any exercises then," Scott said. "I just had my radiation, then go back home. I come back the next day, radiation."

Springer said that treating dysphagia head-on is a developing field. There's not much research on the subject compared to other life-altering conditions, she said.

"Years ago, if people had a swallowing problem, they just realized there was nothing they could do for them, or maybe just modify their diet, and that was it," she said. "But no one wants to be on a puree diet any longer than necessary. So that's always our last resort."

One of those helping to build the body of dysphagia research is Dietsch. Before joining the faculty at UNL last fall, she spent three years conducting dysphagia research during a post-doctoral fellowship at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center.

The primary goal of the residency was to build a massive database to track dysphagia treatment in a group of patients who had not been studied much previously — those who lost some or all of their swallowing capabilities after experiencing combat-related trauma. Far and away, Dietsch said, the group members she worked with were young men who had sustained blast-related injuries or gunshot wounds. As they recovered from traumatic brain injuries, shrapnel damage and the like, they also couldn't eat.

"These are the guys who — let's face it, an 18- to 25-year-old population, if you brought in 10 Dominos pizzas and you turned to pay the delivery guy, all of the pizza would be gone by the time you turned back," she said. "To tell them, 'Hey, you've been overseas eating MREs for the last however many months you've been deployed, and now you are in delivery distance of 875 restaurants and you can't have any of it,' it does not go over well."

As a graduate student, Dietsch voluntarily went on an extended diet of pureed or otherwise viscous fluids in an effort to experience, as best as she could, the diet limitations many people with dysphagia endure. She can no longer stomach yogurt because of it.

"Pureed pepperoni pizza is not as bad as you would think," she said. "Pureed salad with Italian dressing is not good — for future reference."