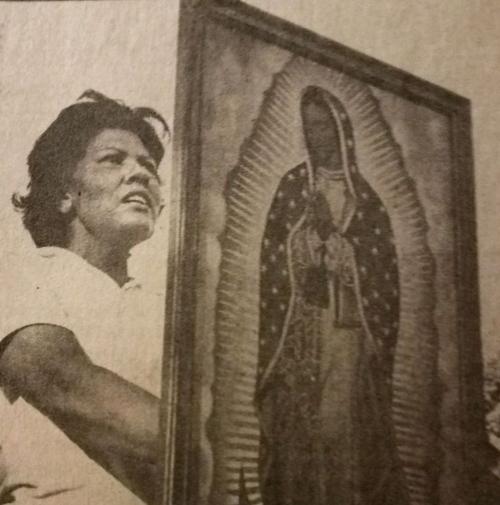

Social justice advocate Guadalupe “Lupe” Sinohui, known for her work helping the poor, marching in the streets in support of labor leader Cesar Chavez and her struggles to shed light on the killing of her son by a South Tucson police officer, died peacefully at home June 23.

Guadalupe Sinohui was the director for the Pascua Neighborhood Center until 1990.

After suffering a hemorrhagic stroke, Sinohui, 88, asked to leave the hospital and go home where she was placed in hospice and cared for by family, said her daughter Anna Sánchez.

“I have been fortunate to have had many wonderful teachers in my life. My mother was my first,” said Sánchez, recalling her mother’s life at Sinohui’s funeral Mass at the downtown St. Augustine Cathedral July 1.

“She taught me the importance of family, to take pride in hard work, to take pleasure in the good that life has to offer and to face the bad with an unending faith in God. By example, she taught us that it is important to take a stand against injustice,” said Sánchez, one of four surviving daughters. Sinohui left 10 grandchildren, 14 great-grandchildren and three great-great-grandchildren.

Sinohui’s oldest grandson, Joseph Hernandez, 48, described his grandmother as “a special lady who impacted many lives. She taught me my faith. She taught me to trust in God and to rely on prayer. She lives on in me and all those she touched by her love, wisdom, conviction and the beauty of her soul.”

In 1977, Lupe Sinohui and her family were put in the national spotlight after son, Jose, 24, was killed by Officer Christopher Dean of the South Tucson Police Department during a disturbance at a fast-food restaurant on South Sixth Avenue, south of Interstate 10.

Tucson police asked for assistance when a melee broke out between youths numbering from 30 to 150, according to media accounts. Jose Sinohui was not involved in the fighting, but rather wanted to leave the area in his 1954 pickup and was traveling south on Sixth Avenue when Dean said he believed Jose was trying to run him over.

Dean fired seven times, striking the back of the truck five times, and the fatal .45-caliber bullet lodged in Jose’s lower back. He died at the Veteran’s Hospital three hours later.

Dean was acquitted of an involuntary manslaughter charge by an all-white jury, and later faced a federal government investigation that ended with prosecutors declining to keep the case going.

In a civil judgment, Superior Court Judge Ben C. Birdsall awarded the Sinohui family $200,000 in punitive and compensatory damages, saying Jose’s civil rights were violated when he was shot. Birdsall found there was no evidence the truck was ever aimed at Dean.

For two years, the Sinohui family and friends held a weekly vigil asking for the U.S. Justice Department to conduct an investigation into the shooting. During this time, the family received “vicious hate mail and telephone calls,” said the Rev. Ricardo Elford, a friend of the Sinohui family, who stuck by their side.

David Yetman, a research social scientist at the University of Arizona Southwest Center, met Lupe when he was serving on the Board of Supervisors. “I felt terrible for her loss. I met her at the vigil at the federal building. She knew what justice was and demanded it,” said Yetman after the funeral.

It was this strength and conviction that family and friends said they learned from Lupe Sinohui, whose maiden name was Ruiz. She was born Dec. 30, 1928, to Gertrudes and Pedro Ruiz, of Opata indigenous blood from Northern Sonora.

Sinohui, who was born in Twin Buttes, loved to ride horses and would wander the open range where her father taught her about desert vegetation.

Lupe was born in Twin Buttes on the east flank of the Sierrita Mountains, about 20 miles south of Tucson. Her father was a miner who worked at mining camps, including Twin Buttes and Ruby and the family also lived in Arivaca and Nogales.

Sinohui was a spirited child who loved to ride horses in Southern Arizona, wandering the open range where her father taught her about desert vegetation and to respect Mother Earth, recalled Sánchez. She also learned from her parents to give of herself and help those in need.

The family moved to Nogales when Sinohui was 12 and she left school in the sixth grade when a new teacher “terrorized the class into only speaking English,” said Sánchez, recalling her mother’s stories. Lupe worked as a waitress and at 17 met her future husband, Joe H. Sinohui, who lived in Patagonia and had recently returned after serving in combat in World War II.

The couple married in 1946 and moved to Tucson where they raised five children. Joe worked as an aircraft mechanic, then eventually became a mining mechanic and Lupe worked for the Saint Vincent de Paul Society, a Catholic organization that works with the poor.

She also was active as director for the Pascua Neighborhood Center in Old Pascua Yaqui Village, which is east of Interstate 10 and south of West Grant Road. During her 14 years at the center, retiring in 1990, she worked helping families find employment and obtaining social services, including assistance with food and clothing. She also secured community development block grants for programs and worked on new housing for residents.

Sinohui, along with the village tribal council, supported Tucson police officers in cleaning up the village of drug dealers selling heroin, curbing domestic violence and clearing property of junked vehicles. Officers also raised money for holiday programs for children, and organized field trips for teenagers to interest them in academic and sports programs at the University of Arizona.

Sinohui practically lived at the village during religious celebrations and attending to families at funeral services. “Lupe cared about people and worked to help those in need,” said Tony Acuña, a resident of Old Pascua who met Sinohui in 1979. “She always was positive and worked to get things done.”

At her grave site on green grass at Holy Hope Cemetery, Elford blessed his dear friend’s wooden casket explaining “nothing dies, rather life is transformed into new life.” Family and friends said their final goodbyes and took a handful of dirt and laid a red rose or carnation on top of the casket before it was lowered into the ground.