A network of independent, off-site air-quality monitors for a controversial south-side ceramics plant may be dismantled, leaving behind only the plant’s existing in-house monitoring system.

The possibility of shutting down the outside monitoring system for Materion Ceramics Inc. has prompted a debate between company and Pima County officials and neighborhood and environmental groups over the desirability of relying on self-monitoring of the plant’s air-quality impacts.

The company, formerly called Brush Ceramics and Brush Wellman, had a history of worker health problems in the 1990s and early 2000s, and was fined $145,000 long ago for air-quality violations.

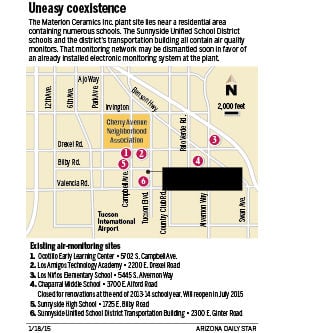

The debate comes as the county considers a proposed revision to its air-quality permit for the plant that for the first time would include requirements for the new monitoring system. The Materion plant, the nation’s largest manufacturer of beryllium oxide products, is at 6100 S. Tucson Blvd., north of Valencia Road, in a residential neighborhood with numerous nearby schools.

After the county holds an open house on Thursday and considers written comments, Pima Department of Environmental Quality Director Ursula Nelson will decide whether to approve the permit. If she does, the monitoring study the county has run for more than seven years for the site will be finalized, and the monitors will be shut down.

Called superior

Materion says the electronic-based, in-house monitoring system it’s had since 2011 is technically superior and will provide air-quality data far more quickly than the outside monitoring network can.

Materion’s Triboelectric particulate monitoring system measures particles as they pass over or near a series of five electronic detection probes. The probes create an electronic current in response to the emissions dust. The probes are installed into the ductwork of the plant’s venting system.

The current system of outside air monitors operates in five nearby schools and a transportation building in the Sunnyside Unified School District. Materion pays about $10,000 a year for the monitors’ air filters, and to operate the monitors and analyze the monitoring data. Sunnyside pays about $7,500 a year for staff time to install and remove filters. Pima County’s staff calibrates the monitors and collects the filters when the schools are shut down, but county officials couldn’t estimate their costs.

The Materion plant also has a separate conventional testing system for emissions rising through the plant’s stack, a system the company also plans to scrap if the permit revision is OK’d.

Beryllium, a naturally occurring metal, can be toxic when particles are inhaled. But the current Materion monitoring network has found only one air sample containing beryllium in more than seven years, and that one from 2009 likely was naturally occurring, a county consultant has said.

With the plant’s newer system, alarms are triggered if the electronic currents rise to levels that suggest problematic levels of dust emissions. That gives plant officials the chance to investigate the problem and shut the plant down if necessary, said Ken Harrison, the plant manager.

“It’s a real-time feedback on the performance of air pollution controls,” Harrison said.

It takes 45 days for company officials to get lab analysis data from air samples taken annually from its old stack emission system. It takes three months to get data from the outside monitors, which operate continuously.

But the new system is hooked to a data logger that produces data within a few minutes, Harrison said.

Rather keep old system

A neighborhood association and an environmental justice activist said they’d rather keep the outside monitoring system to have a check on the company.

“We don’t mind that they self-test,” said Cheryl Strickland, president of the Cherry Avenue Neighborhood Association, whose southern boundary is a half-mile north of the plant site but whose turf lies within the Sunnyside District. “We’d like to see someone other than them testing themselves, to be absolutely sure.”

Self-monitoring is convenient for the county, but it raises the possibility that people will manipulate the data, said Rob Kulakofsky, an activist with the Environmental Justice Action Group. “I’m not saying they would, but their past experience hasn’t been too good. I’d rather see someone else doing the monitoring,” he said.

But self-monitoring by Materion would be no different from what happens at the area’s copper mines and at Tucson Electric Power Co.’s south-side Sundt Generating Station, PDEQ officials say.

The current Materion electronic monitoring system was developed in response to requirements put into the 2006 permit — at the environmental justice group’s request — that the company research new monitoring technologies, a PDEQ official said.

“The new system will be much more protective of public health. We and the company will know in a short period if there is a problem,” said Beth Gorman, a PDEQ program manager. “They will be using this particulate detection system in their stack so they would be able to know right away if there is any kind of a leak.”

The new system’s particulate detectors can’t detect beryllium particles, but they can detect changes in the amount of total particulate matter emitted through the stack, Gorman said. This approach would immediately detect any failures of the plant’s primary air filters, she said.

The proposed permit revision also would require Materion to operate particle detectors at any time its air filtration system is on and set off alarm systems within the facility if particle readings exceed a set level, she said. The company would have to keep records of stack emissions, and PDEQ inspectors could conduct unannounced plant inspections, as they can at any permitted facility, Gorman said.

Kulakofsky agrees that real-time testing is a great idea, but he’s concerned that there won’t be specific beryllium tests.

“I’m concerned that what they’ll be showing is dust coming out of stack. It will look like more of a clarity issue,” he said. “There is no proof of whether that dust contains beryllium.”

Materion’s Harrison countered that like the outside monitors, the plant’s older stack testing has never detected beryllium from the plant, suggesting it has no beryllium problem. The new system measures all dust emissions — not just beryllium, he said.

Sunnyside is neutral

The Sunnyside School District isn’t taking sides.

The district is extremely sensitive about environmental-health issues, given Brush’s history and the unrelated history of groundwater contamination from trichloroethylene in the community, said Hector Encinas, Sunnyside’s chief financial officer. But officials don’t have the expertise to determine if the self-monitoring system or the outside monitoring works best, Encinas said.

“We want to make sure the necessary safeguards are in place,” Encinas said. “If the changes guarantee the safety of the facility and are an improvement over current monitoring, we support any measures that are an improvement. If they don’t, we can’t support that.”

Back in 2006, Brush Ceramics and PDEQ signed an agreement calling on the company to pay to operate the monitors. The agreement was signed around the same time the county approved an earlier air-quality-permit revision. The agreement has already run out, however, meaning that the county would have to find another money source to keep operating the outside monitors if it doesn’t approve the permit revision as proposed, Gorman said.

In the past, the Star has reported that 35 workers at the plant had contracted incurable chronic beryllium disease, which slowly suffocates its victims. In 2009, the U.S. Department of Justice announced that it had paid $1.4 million to compensate or care for victims of that disease who worked at the site.

In 2001, Brush Wellman agreed to pay a $145,000 fine for violating county air quality rules after an earlier inspection revealed a clothes dryer was illegally venting air to the outside. The drier laundered worker uniforms tainted with toxic beryllium dust.